Local government in Colombia

Colombia’s regional and local elections will be held on October 29, 2023.

Voters across the country will elect governors, mayors, members of municipal councils (concejos municipales), departmental assemblies (asambleas) and local administrative boards (juntas administradoras locales, JAL). Local officeholders serve four-year terms, which begin on January 1.

The first article of the Constitution defines Colombia as a “unitary decentralized republic with autonomy of its territorial entities.” Territorial entities are constitutionally defined as departments, districts, municipalities and indigenous territories, and allows for regions to eventually become territorial entities.

While the 1991 Constitution opened the way for extensive decentralization, in practice, Colombia remains a fairly centralized country, in good part because territorial entities have a weak fiscal capacity in all but a few cases. Nevertheless, the governors of larger departments and the mayors of big cities have become important political figures and the mayor of Bogotá is often said to be “the second most important public office in Colombia”, right behind the President.

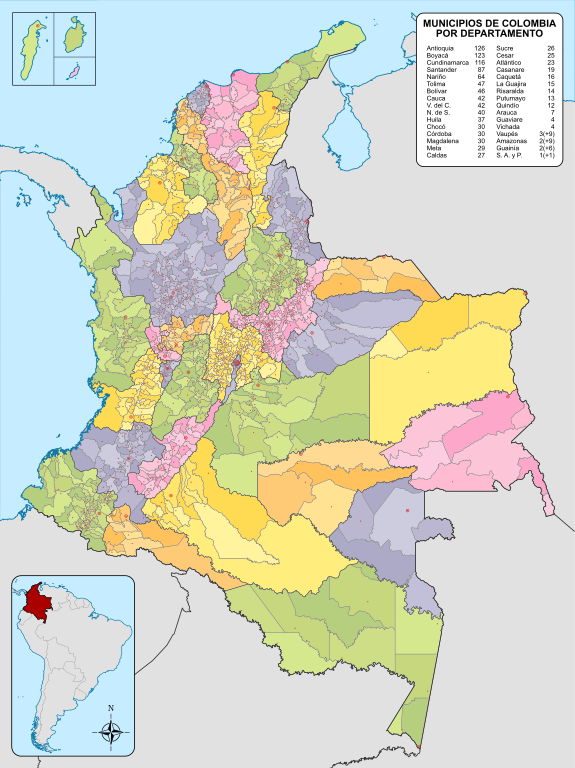

Essentially, Colombia’s 32 departments are the first-order administrative divisions (similar to states or provinces), while the 1,102 municipalities or districts are the second-order administrative divisions. Bogotá, the Capital District (Distrito Capital), has a special status as it is not part of any department (it is usually counted as a municipality).

Territorial organization of Colombia

Territorial entities are constitutionally defined as departments, districts, municipalities and indigenous territories (which have self-government), and allows for regions to eventually become territorial entities. Territorial entities enjoy autonomy for the management of their interests, within the limits of the Constitution and the law, and have the right to govern themselves by their own authorities, exercise the powers that correspond to them, manage fiscal resources and establish the necessary taxes for fulfillment of their functions and to participate in national revenues.

Decentralization in Colombia is recent, dating back to the 1991 Constitution, which defined the country as a “unitary decentralized republic”, enshrining the autonomy of territorial entities and providing for the direct election of both mayors and governors (direct election of mayors was introduced in 1986).

Decentralization was a key element of the democratization of Colombia’s political system in the 1991 Constitution, responding to popular demands for greater political participation. The 1886 Constitution, a conservative and positivist reaction to the confederalist Rionegro Constitution of 1863, established an ultra-centralist unitary state inspired in part by republican France. Governors were appointed by the president, and mayors in turn were appointed by the governor. Only in 1968 was the ‘independence’ of departments to manage their own affairs recognized, and only in 1986 was the constitution amended to allow for the direct election of mayors (the first elections took place in 1988).

While decentralization was seen as a means to re-legitimize and democratize a broken and closed political system by fomenting participative democracy, it also resulted in violent competition for power and provided a very favourable opportunity structure for criminal interests and illegal armed groups. Local governments’ revenues increased considerably, but remained dependent on transfers from the central government. Illegal groups, but also legal or ‘hybrid’ corrupt/criminal private interests (contractors, businesses and corporations), have taken advantage of decentralization to infiltrate and ‘capture’ local governments and access to public funds.

Departments

Colombia is divided into 32 departments (departamentos). Article 298 of the Constitution defines the autonomy and general role of departments:

The departments enjoy autonomy for the administration of sectional matters as well as the planning and promotion of economic and social development within their territory, within the limits established by the Constitution.

The departments exercise administrative functions of coordination, of complementarity with municipal action, of intermediation between the nation and the municipalities, and the provision of services determined by the Constitution and the laws.

Departments were created in 1886, replacing the sovereign states of the confederal United States of Colombia (1863-1886). The number of departments grew from nine in 1886 (including Panama) to 23 in 1990. The 1991 Constitution elevated the nine national territories (territorios nacionales)—peripheral areas were directly administered by the central government as commissariats (comisarías) and intendencies (intendencias)—to the rank of departments.

Each department is administered by a directly-elected governor (gobernador), who is the head of the local administration, legal representative of the department and the agent of the President for the maintenance of public order and implementation of national policy. Governors are elected for four-year terms by first-past-the-post, and may not serve consecutive terms. The governor manages and coordinates the public administration of the department (appointing and dismissing public officials, including managers of public enterprises etc.); promotes the cultural, social and economic development of the department; appoints members of cabinet; presents projects of ordinances to the departmental assembly and enforces the Constitution, national laws and departmental ordinances.

The departmental assembly (asamblea departamental) is a directly-elected deliberative body, made up of no less than 11 members and no more than 31 members according to the Constitution. In practice, the largest assembly, that of Antioquia, currently has 26 members while the smallest ones have 11 members. The first runner-up in gubernatorial elections is entitled to an ex officio seat in the departmental assembly. Members of departmental assemblies are known as deputies (diputados) and are elected for four-year terms, with no term limits, using the same electoral system as in congressional elections (open or closed-list proportional representation using the d'Hondt/cifra repartidora method, the threshold is half the quota). 418 deputies will be elected in 2023.

Departmental assemblies are not legislative bodies, and are instead ‘political-administrative’ deliberative bodies which adopt their decisions through ordinances and resolutions. They enact regulations on matters within their areas of responsibility, decree local taxes and levies, adopt development plans, authorize the governor to sign contracts and negotiate loans and determine the structure of the departmental administration. Assemblies also exercise political oversight and they may summon cabinet secretaries to oversight hearings and propose motions of no confidence against them (removal requires a two-thirds majority). Departmental assemblies have been directly elected since 1905.

Bogotá has a special status as the Capital District and is not part of any department, but is nevertheless the capital of the department of Cundinamarca.

The department of the San Andrés and Providencia has special, additional powers on matters including local administration, immigration, land use, culture, taxation, environmental preservation, foreign trade, finance and economic development. It is a free trade zone with a special customs and taxation regime (no customs tariffs, reduced consumption tax, VAT exemptions on certain transactions, special contribution for tourists and temporary residents) as well as special immigration rules (special permanent and temporary residency statuses, population density controls).

Municipalities and districts

Colombia has 1,102 municipalities (municipios) and districts, including Bogotá (Capital District). Although they are second-level administrative divisions, municipalities are, under the 1991 Constitution, the “fundamental entity of the political-administrative division of the state.” Article 311 of the Constitution defines the basic functions of municipalities:

As the fundamental entity of the political-administrative division of the State, it is the responsibility of the municipality to provide those public services determined by law, to build the projects required for local progress, to arrange for the development of its territory, to promote community participation, the social and cultural betterment of its inhabitants, and to execute the other functions assigned to it by the Constitution and the laws.

Municipalities have some important powers and responsibilities including land use, spatial planning, promotion of local development, local security, housing, provision of utilities, public transit, school lunches and local roads.

There are currently a total of 1,102 municipalities in Colombia. Antioquia (125) and Boyacá (123) have the most municipalities. Five municipalities, including Bogotá, have over one million inhabitants (Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, Barranquilla, Cartagena) and another 94 have over 100,000 inhabitants. Municipalities vary widely in land area and population.

Some parts of the Colombian territory are not part of any municipality. The island of San Andrés is not a municipality and is directly administered by the department, leaving the island of Providencia as the department’s only municipality. Large, remote and very sparsely populated areas of the Amazon in the departments of Amazonas, Vaupés and Guainía are directly administered by the department as corregimientos departamentales or áreas no municipalizadas, of which there are currently 18. These areas do not elect mayors or municipal councillors.

The mayor (alcalde) is the head of the local administration. Mayors are elected for four-year terms by FPTP (except in Bogotá), and may not serve for consecutive terms. The mayor manages and coordinates the public administration of the municipality; maintains public order; promotes local development; appoints members of cabinet (known as secretaries); presents proposals to the council and enforces the Constitution, laws, departmental ordinances and local resolutions.

The municipal council (concejo municipal) is a directly-elected deliberative body made up of no less than 7 members and no more than 21 members. The size of the municipal council—always an odd number—varies according to the municipal population, with cities of over 1,000,000 inhabitants electing 21 councillors and municipalities with less than 5,000 inhabitants electing 7. The first runner-up in the mayoral election is entitled to an ex officio seat in the municipal council. 12,072 councillors will be elected in 2023.

Councillors (concejales) are elected for four-year terms, with no term limits, using the same electoral system as in congressional and assembly elections. Municipal councils are deliberative bodies which adopt their decisions through agreements (acuerdos). Councils enact regulations on matters and services within their areas of responsibility, decree local taxes and levies, adopt development plans, adopt the budget, regulate land use, authorize the mayor to sign contracts and determine the structure of the local administration. Councils also exercise political oversight and they may, since 2007, summon cabinet secretaries to oversight hearings and propose motions of no confidence against cabinet secretaries (removal requires a two-thirds majority). Municipal councils have been directly elected since their creation in 1886.

Municipal councils may divide the municipality into comunas (in urban areas) and corregimientos (in rural areas), “in order to improve the provision of services and ensure the participation of citizens in the management of local public affair.” Comunas are usually made up of one or more neighbourhoods (barrios), while corregimientos are made up of several veredas.

Each comuna and corregimiento has a directly-elected Local Administrative Board (Junta Administradora Local, JAL) made up of no less than 3 and no more than 9 members, who are known as aldermen (ediles) and serve four-year terms with no term limits. The JALs participate in the elaboration of municipal plans and programs, oversee and control the provision of local services, formulate investment proposals, deliver non-binding statements about new building projects, promote local small businesses, encourage civic participation and other powers which may be delegated to it by the municipal council. JALs were created in 1968. 6,885 aldermen will be elected in 2023.

Bogotá, Capital District

Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, is administered as the Capital District (Distrito Capital, DC) under a special administrative regime. In 1954, Bogotá was made a special district administratively separate from Cundinamarca, and with the annexation of neighbouring municipalities it gained its current boundaries. With the 1991 Constitution, Bogotá became the Capital District. Bogotá is neither a department nor a municipality (but often gets counted as a municipality), and as a de facto first-level administrative division, Bogotá holds the powers and responsibilities of both a department and municipality.

The Superior Mayor of Bogotá (Alcalde Mayor), the head of the local administration, is directly elected for a four-year term and may not serve consecutive terms. For the first time this year, the mayor of Bogotá will be elected in a two-round election, with a runoff being held three weeks later if no candidate has won 40% with a 10% lead over second.

The mayor of Bogotá’s duties and powers are broadly similar to those of other mayors in the country, but because of the size and importance of the city, the office is often considered as the second most important elected office in Colombia after the President.

Bogotá’s city council, officially known as the District Council (Concejo Distrital), is made up of 45 directly-elected councillors who serve four-year terms (with no term limits).

Bogotá is divided into twenty localities (localidades). Each locality has a directly-elected JAL, made up of at least 7 aldermen (ediles), and a local mayor (alcalde local). Local mayors are appointed by the senior mayor from a list of three names selected by the respective JAL, and local mayors may be dismissed at any time by the senior mayor. Localities have somewhat greater powers than comunas, notably managing and distributing a small portion of the city’s budget and having some powers over the use of public spaces.

Other administrative divisions

The Constitution and laws allow for and have created a large number of other administrative divisions or structures, not all of which are territorial entities.

Districts

Besides Bogotá, there are currently eleven districts (distritos): Barrancabermeja, Barranquilla, Buenaventura, Cali, Cartagena, Medellín, Mompox, Riohacha, Santa Marta, Tumaco and Turbo. Unlike municipalities, districts are created by laws passed by Congress.

Districts have greater powers than municipalities, notably to regulate tourism, culture, recreational activities and environmental protection as well as in the promotion and coordination of economic development. One of the common justifications for the creation of special districts is to better promote economic and social development in lower-income municipalities (like Buenaventura, Tumaco, Turbo, Riohacha), although it is not clear if the special status is of any real value in the long-term.

Districts are subdivided into localities (localidades), which each have a directly-elected JAL and a local mayor appointed by the district mayor (alcalde distrital) from a list of three names selected by the JAL. Like in Bogotá, localities have greater prerogatives than comunas and administer a small budget (local development fund). At least 10% of the district’s revenues are earmarked for the localities.

Metropolitan areas

The Constitution allows two or more municipalities which are linked by various dynamics (economic, territorial, social, cultural, demographic etc.) to form metropolitan areas (Áreas Metropolitanas) in order to program and coordinate the development of the territory, rationalize the delivery of public services including public transit, jointly provide some of them and carry out projects of metropolitan interest. Metropolitan areas are not territorial entities but have a special administrative and fiscal regime.

Metropolitan areas may be created at the initiative of a governor, mayors, a third of councillors or 5% of citizens of the respective municipalities. A referendum on the proposal is held in each of the municipalities, and approval requires an absolute majority and at least 25% turnout in each municipality.

Each metropolitan area has a metropolitan board (Junta Metropolitana), which is made up of the mayors of all municipalities, a representative from the core municipality’s municipal council, a representative from the other municipal councils, a non-voting permanent delegate of the national government and one representative from local NGOs dedicated to ‘environmental protection and renewable natural resources’. The president of the board (Presidente de la Junta Metropolitana) is the mayor of the core (largest) municipality. There is also a director of the metropolitan area, a senior bureaucrat, who is selected by the metropolitan board from a list of three candidates submitted by the mayor of the core municipality.

There are six legally recognized metropolitan areas: the Valley of Aburrá (Medellín), Bucaramanga, Barranquilla, Centre West (Pereira), Cúcuta and Valledupar. Medellín’s metropolitan area is the oldest and largest, with 10 municipalities and over 4.2 million inhabitants. Another 15 or so metropolitan areas exist de facto, not legally recognized.

Regions

The Constitution allows two or more departments to form administrative and planning regions (Regiones administrativas y de planificación, RAP), which may later be transformed into territorial entities (Regiones entidades territoriales, RET). Political interest in the creation of regions associating two or more departments is fairly recent, and received a major impetus with the 2011 territorial planning organic law and the 2019 regions law. The aim of regions is to promote regional socioeconomic development, regional investment and competitiveness.

Administrative and planning regions (RAPs) are formed by the governors of two or or more contiguous departments, with prior opinion of the Senate’s territorial organization commission and prior approval of their respective departmental assemblies. Departments may belong to more than one RAP. There are currently nine RAPs in Colombia and every department except for San Andrés is part of at least one region. These administrative regions have, among other things, the power to lead projects of regional interests. However, as currently designed, RAPs are essentially associations of departments with few substantive powers besides vaguely worded lofty goals, and few resources of their own besides.

The 2019 regions law also provides for the eventual conversion of RAPs into RETs after at least five years, subject to congressional approval and a regional referendum. These regions, as territorial entities, would enjoy somewhat greater budgetary autonomy and could have specific powers devolved to them by the national government. Departments would only be able to belong to one RET.

In addition, the Metropolitan Region of Bogotá-Cundinamarca was created in 2020 and regulated by organic law in 2022. This new region with special status is supposed to allow Bogotá and nearby municipalities to solve common problems like transportation, security, sustainable development and economic development. The metropolitan region will include Bogotá, the departmental government of Cundinamarca and the municipalities which choose to join it. It will be led by a regional council which will include the mayor of Bogotá, the governor of Cundinamarca and the mayors of all associated municipalities with representatives from the national government. Decisions in the council are to be based on consensus as much as possible.

The metropolitan region will have powers in the areas of mobility (transportation), security, food security, public utilities, economic development, environment and housing/spatial planning.

Decentralization in question

The 1991 Constitution made Colombia a decentralized unitary republic, accompanied by significant fiscal decentralization (a process that had begun decades earlier).

Subnational governments account for a substantial of general government expenditure. In 2017, according to the OECD’s Government at a Glance publication, municipalities and departments accounted for about 36% of general government expenditure, comparable to Brazil, a federal country. Subnational governments have important responsibilities on issues like education, healthcare, public utilities and transportation, often shared with the national government and other levels of government.

However, municipalities and departments remain dependent on grants and transfers from the national government. In 2021, transfers and royalties accounted for 50.3% of territorial governments’ revenues while 33.6% came from their own sources of revenue (taxes, contributions, fees and fines). Departments and municipalities have little freedom to determine how to spend their revenues.

The main source of transfers to territorial entities is the Sistema General de Participaciones (SGP), a revenue-sharing system created in 2001. The transfers in the SGP are virtually all earmarked: for education (56.2%), health (23.5%), water and sanitation (5.2%), general purposes (11.1%) and special allocations (4%). The ‘general purposes’ transfers are primarily intended for poorer and smaller municipalities, and some of these funds are earmarked for sports, culture and pension obligations. SGP transfers increase annually according to a constitutional formula, and will amount to 70.5 trillion pesos ($17 billion) in 2024.

Subnational governments also receive royalties through the Sistema General de Regalías (SGR). The distribution of royalties is defined in the constitution, with about a quarter going to resource-producing departments and municipalities, 15% for the poorest municipalities and 34% for investment projects in regions, departments and municipalities. Royalties are to be used to finance various investment projects that contribute to local social, economic and environmental development. The Duque administration’s 2019-2020 royalties reform gave territorial entities greater discretion in how they spend royalties, simplifying the planning and approval procedures for investment projects funded by royalties.

Local governments’ revenue-raising powers are weak. The main departmental taxes are consumption taxes on beer, liquor and tobacco, a tax on vehicle ownership, a gasoline tax surcharge, stamp taxes and registry taxes. However, most tax rates are set nationally and a portion of the tax proceeds are earmarked.

Municipalities have higher tax revenues than departments and more autonomy in applying and spending these taxes. The two main local taxes are property taxes and a business turnover tax known as the industry and commerce tax (ICA), which make up about two-thirds of local tax revenues. Tax rates are set locally within a nationally-defined range. Municipalities also receive part of the vehicle ownership tax and gasoline surcharge, and several indirect taxes and levies. Municipalities may impose additional contributions like valorización (special assessment) and plusvalía for changes in land value related to public infrastructure or land use changes, respectively.

Larger, wealthier departments and municipalities have much stronger revenue-raising capacities and are less dependent on transfers. Bogotá has, by far, the strongest revenue-raising capacity and transfers make up just around 20% of its total revenues. However, for poorer departments like Córdoba, Sucre, Cesar and Cauca, to name just a few, transfers can account for up to three-quarters of their total revenues.

Dependence on transfers explains why most mayors and governors need to maintain good relations with the national government, regardless of political differences. In contrast, the mayor of Bogotá, who isn’t as reliant on transfers, can afford to be more critical of the president and government at times—within limits.

About 83% of local government spending are for ‘investments’ (in education, healthcare etc.) and 14.5% in operating expenses. Since the late 1990s, the national government has imposed strict limits on operating expenses and barred local governments from using transfers to pay for operating expenses.

The issues of decentralization and territorial autonomy have been in the public debate for years. Earlier this year, governors met in Rionegro to commemorate the 160th anniversary of the Rionegro Constitution of 1863 and issued a sort of manifesto for “true territorial autonomy.” This ‘federalist manifesto’ complains that the decentralization and territorial autonomy promised by the 1991 Constitution remains unfulfilled, but the document is mostly a vague declaration of principles and objectives rather than a proposal for a new territorial organization. The governors’ main complaint is that their revenue-raising powers are far too limited and that local governments are seen as weak and incapable. While some politicians on both the left and right have advocated for decentralization or federalism for years, this particular moment can’t be separated from the current political context and the political ambitions of certain governors.