Year Three

The third year of Congress began on July 20. A look at the new congressional leadership, the government's legislative agenda and Petro's speech to Congress.

On July 20, Gustavo Petro opened the third year of Congress. On August 7, Petro passed the halfway point of his term.

Year Three

Congress sits for two ordinary sessions in one legislative term (legislatura)—from July 20 to December 16, and from February 16 to June 20.

A series of rituals governs the beginning of the new legislative year. The first session is formally opened by the President, speaking before a joint session of both houses. Both houses renew their leadership—unlike in most countries, the congressional leadership is renewed in full each year, and reelection is not permitted. The commissions in both houses also elect their new presidents.

At the start of a new Congress, the main parties typically divide the presidencies of both houses amongst themselves for the next four years. The political agreements are respected, with other parties supporting whichever candidate is put forward by the party whose turn it is to hold the presidency. For 2024-25, the presidencies of the Senate and the House are ‘reserved’ for the Conservatives and the Greens, respectively.

The presiding officers have quite a bit of power, controlling the agenda and schedule, deciding when and in what order bills are debated. They can be of great help to a government, or real nightmares.

No drama in the Senate

Unlike a year ago, there was no drama in the Senate. The presidency falls upon the Conservatives for the year, and the party settled around the name of senator Efraín ‘Fincho’ Cepeda without much trouble a while ago.

Efraín Cepeda is the longest-serving incumbent senator, having been first elected in 1991 and reelected eight consecutive times since. Cepeda is one of the most experienced and seasoned legislators in the country, and a shrewd politician and skilled political maneuverer. He’s adept at oiling his political machine in Atlántico, weaving alliances, winning votes (he was reelected with 132,800 votes in 2022), managing bureaucratic ‘quotas’ through different administrations and being a major player in the Senate and the economic commissions (he already was president of the Senate in 2017-2018). His relatives, former staffers and political allies hold important positions at different levels and branches of government—an old ally of his, Carlos Mario Zuluaga, is currently deputy comptroller general—or have obtained public contracts. Cepeda and his family are part of the elite dominating the imbricated world of politics and big business in Barranquilla: his family owns Cepeda & Cia., a major real estate company in the city, and his son Efraín Cepeda Tarud is currently president of the Comité Intergremial del Atlántico (the association of local sectoral associations and big corporations).

Like most Conservative congressmen, Cepeda doesn’t like being in opposition—he’s hardly ever really been in the opposition over his career—and he’s usually maintained good relations with successive administrations.

Cepeda has been a leading figure in the Conservative Party for decades, and he’s held the party presidency on three separate occasions since the 2000s. Most recently, Cepeda took the party leadership in February 2023 after an internal coup, masterminded by Cepeda and others, toppled senator Carlos Andrés Trujillo, Petro’s closest ally in the party. Senior party figures grumbled that Trujillo and his inner circle kept all the party’s bureaucratic ‘quotas’ for themselves.

The Conservatives formally quit the governing coalition in May 2023 and Cepeda has adopted a stance of ‘critical independence’ towards the government, strongly opposing the healthcare and pension reforms without going into ‘full’ opposition. Earlier this year he staged a show of force to reassert his power, after Petro appointed Luz Cristina López, who is seen as a ‘quota’ of Conservative rep. Alfredo ‘Ape’ Cuello, as sports minister. Cepeda offered his resignation as party president, only to have it (as expected), unanimously rejected by the party exec and his leadership (and political strategy) fully endorsed. Nevertheless, Cuello has been able to keep his ‘quota’ without too much trouble from the party leadership and the government can still rely on the help of a number of friendly Conservative congressmen in the House (and, to a much lesser extent, in the Senate).

With the support of other parties in Congress, Cepeda was elected unopposed, receiving 97 votes. In remarks after his election, Cepeda assured that all legislative initiatives would receive the same treatment. As president of the Senate, Cepeda faces a dilemma: remain in ‘critical independence’ and be a counterweight to the administration, or, pushed by his party’s ‘bureaucratic appetite’, negotiate a good working relationship with the government. The siren calls and bureaucratic temptations will be hard to resist for Conservative congressmen as 2026 draws nearer...

The first vice presidency, which goes to the Liberals this year, was won by Antioquia Liberal senator John Jairo Roldán with 80 votes, fending off a last-minute challenge by Karina Espinosa, who got 17 votes. Roldán has been critical of Petro on several occasions, but has voted with the government on some issues. The second vice presidency, reserved by law for the opposition, was won by uribista senator Alirio Barrera with 94 votes. By law, the first vice presidency is reserved for ‘political minorities’, a vague term left undefined until earlier this year, when the Council of State nullified the 2023 elections of the first vice presidents of both houses on these grounds, but that verdict hasn’t been set in stone yet.

The Green battle for the House

Per the terms of the deals sealed in 2022, the presidency of the House for the third year is reserved for the Greens. Much like their colleagues in the Senate a year ago, the Greens in the House were unable to agree on a name amongst themselves, taking their battle to the floor of the House. The Greens are deeply divided with unresolved internal contradictions and politically split between petristas and increasingly anti-petrista centrists.

The closely-fought election opposed Boyacá representative Jaime Salamanca to Bogotá rep. Katherine Miranda. In the end, Salamanca, the government’s favourite, was elected with 114 votes against 69 for Miranda.

Jaime Raúl Salamanca is a first-term representative from Boyacá, from the political group of governor Carlos Amaya. Amaya, who ran for president in 2022 (he finished a strong third with 21% in the centrist primary), opposed Petro in 2022 and voted for Rodolfo Hernández in the runoff, but he’s become a key regional ally for the administration since his election to a second (non-consecutive) term as governor last year. Salamanca, however, did vote for Petro in the runoff two years ago.

Katherine Miranda is a two-term representative from Bogotá, first elected in 2018. She entered politics with Antanas Mockus and the Ola Verde in 2010, and remained close to the mockusiano faction of the Greens thereafter. Elected to the House in 2018 with 64,300 votes, she significantly increased her vote in 2022, winning 119,500 votes (the most votes of any individual candidate in the capital). Miranda supported Petro by the first round in 2022 and was one of the campaign’s coordinators. However, she quickly distanced herself from the government and has become a vocal critic of Petro. She opposed the healthcare reform, criticized the way in which the pension reform was adopted, criticized Petro’s ‘total peace’ strategy, clashed with Petro over ‘express expropriation’ and attacked the government’s very ‘traditional’ political practices. She’s accused Petro of “navel-gazing” and ignoring the country’s problems. Miranda says that she remains a centre-left progressive, particularly on moral issues and civil liberties, but more conservative on economic matters. Miranda is a particularly media-savvy politician, very adept at social media and regularly appearing in the press.

Both Salamanca and Miranda claimed to be the most legitimate candidates within their party. Salamanca had the support of a majority (8) of the Greens’ 15 representatives. Four other putative candidates for the presidency, Martha Alfonso, Duvalier Sánchez, Santiago Osorio and Wilmer Castellanos withdrew in his favour. Miranda, on the other hand, pointed to the support of a majority (11) of the 20 representatives from the old Centro Esperanza coalition (the Greens plus Nuevo Liberalismo, Dignidad, Gente en Movimiento, Verde Oxígeno).

Both had strong arguments to justify their candidacies, and both felt that they had a path to victory (94 votes). Miranda bet on a ‘silent majority’—the opposition and independent parties (Conservatives, La U, some Liberals and her half of the Greens/centrists) who’d want to send a message to the government, like their colleagues in the upper house did by electing Iván Name in 2023.

Salamanca’s campaign started slowly, and with much less media attention. He counted on the governing coalition—the Pacto (which made official its support two days prior), the petrista Greens, 13 of the 16 victims’ representatives and those Liberal, Conservative and U representatives who have tended to vote with the government. He was, most importantly, the government’s favourite. Interior minister Juan Fernando Cristo, in office since early July, worked behind the scenes to align forces in his favour. The petrista Greens met with Petro and Cristo in early July.

The government has tended to have a more reliable and solid majority in the House, with around 110 or so potential allies, thanks in part to a few key political operators in the different caucuses. Thanks to Cristo’s discreet maneuvers, momentum shifted in his favour in the final hours. The majority (20-25) of the Liberals (33 seats) supported him and the Partido de la U (16 seats) gave him their support.

Miranda complained that the fight had been “tough, unequal and unfair” because of the government’s favouritism for Salamanca, denouncing interference by cabinet ministers. She made a rather desperate and last-ditch appeal to her colleagues to vote their conscience, for the ‘independence and dignity’ of Congress.

In the end, Salamanca won quite easily, with 114 votes against 69 for Miranda. The vote is secret, but Salamanca likely won with the votes of the Pacto and allies (35), most Liberals (20-25 of 33), La U (15-16), Conservatives (18 or so of 27), the victims’ seats (13 of 16) and the Greens (8). Miranda only got the backing of the opposition (37), Greens and centrists (11) and a minority of the Liberals and Conservatives. It was a first big win for Cristo.

Miranda’s top surrogate, Cathy Juvinao, later claimed that ICT minister Mauricio Lizcano pressured representatives from the Partido de la U (his old party). She said that their ballots had orange markings, allegedly to control that they were voting for Salamanca. Lizcano denied any involvement. In any case, several cabinet ministers, including Cristo, were in the chamber during the election.

The first vice presidency of the House went to Jorge Tovar, one of the victims’ seats representatives, and, most (in)famously, the son of former paramilitary commander Jorge 40. He received 112 votes against 38 for Jhon Freddy Núñez (another victims’ rep.), 26 for Juan Manuel Cortés (Liga, supported by the Conservatives) and 3 for Karen Manrique (victims’ rep). The second vice presidency, reserved for the opposition, saw a close fight and was won by Lina María Garrido (CR) with 90 votes against 88 for Marelen Castillo, Rodolfo Hernández’s former running mate (who now hates her and demands she ‘repays the money’ he gave her in 2022).

The battle in commissions

The presidencies of both houses are important, but the presidencies of each of the commissions in both houses are just as important—that’s where all bills start off.

There are seven permanent constitutional commissions in each house. The ‘political agreements’ in 2022 also divided the presidencies between the parties, but some of those agreements have been broken. The table below shows the presidencies of each commission for 2024-25, with green indicating pro-government, red indicating opposition and yellow indicating independents. In total, six of the 14 commissions are in the hands of allies, and another two or three in the hands of ‘independents’ who could work in tandem with the government.

The first commission is the most high-profile—it handles constitutional reforms, statutory laws and peace. In the Senate, Green senator Ariel Ávila, who has supported the government on peace issues, was elected against right-wing anti-Petro Green ‘Jota Pe’ Hernández, 12 votes to 5, a big win for the government (who had lost it last year). Córdoba rep. Ana Paola García (La U), close to the government, won the presidency of the first commission in the House.

The government will have a tougher time in the economic commissions (third and fourth) in the Senate, which will handle the 2025 budget and an impending tax reform. The third commission will be presided by anti-Petro Liberal Juan Pablo Gallo, while the fourth commission will be presided by Angélica Lozano (Green), who has pushed for her party to quit the governing coalition. However, in the House, both the third and fourth commissions will be in friendlier hands: Kelyn González (Liberal) and José Eliécer Salazar (La U) have both been quite close to the government.

The deals were broken in the fifth commissions (agriculture and environment) in both houses, and the Pacto lost both of them. In the Senate, it’ll be led by Marcos Daniel Pineda (Conservative) and in the House by Octavio Cardona (Liberal), who has been critical of the administration.

The seventh commission has gained in prominence under Petro, responsible for the healthcare and labour reforms. In the Senate, it will be presided by Conservative senator Nadia Blel—who has also replaced Cepeda as president of the party, following his ‘critical independence’ stance towards the government. In the House, the Conservatives will preside it as well, but Tolima rep. Gerardo Yepes has been more helpful to the government’s interests in the past.

Petro’s speech

The other ritual of the first day of Congress is the president’s speech before a joint session of Congress. This year, Petro’s speech was conciliatory and humble.

He began, quite unusually, by apologizing for the UNGRD scandal and taking responsibility for appointing the disgraced former head of the UNGRD, Olmedo López. It was a rare show of humility from the president.

Unlike his 2023 speech, which was more rhetorical and ideological, this year he gave an account of his government’s achievements with some numbers at hand. He celebrated, and took credit for, the growth in agricultural production, the reduction of poverty (which fell from 36.6% in 2022 to 33% in 2023) and a record increase in tourism. He argued that the reduction of poverty was in good part thanks to the government’s substantial increase of the minimum wage (and took the chance to take shots at experts who criticized the big increase in the minimum wage), and used it as proof that the government has been effective and has met its objectives.

Petro announced several legislative initiatives for the next year, including a package to accelerate the implementation of the peace agreement, an economic reactivation package, a public utilities reform, an agrarian reform, a new ‘consensual’ healthcare reform and the conclusion of the labour reform, among others.

At the end of his speech, Petro proposed a ‘national agreement’ (acuerdo nacional)—regular readers of this publication will know that this idea has come up time and time again since 2022, and received a new impetus with the new interior minister, Juan Fernando Cristo.

After months of overheated political rhetoric and animosity with Congress, Petro’s speech was conciliatory and measured. Throughout his speech, Petro was deferential towards Congress and reminded them that he too was once a parliamentarian. He never mentioned the word constituyente (constituent), although he did say that the ‘national agreement’ could include social and political forces outside of Congress. He extended his hand and signaled his willingness to “talk, dialogue and sit down to discuss arguments like good parliamentarians.”

However, the opposition and independents remained incredulous. In his opposition response, CR senator David Luna told Petro that, last year, he had also invited them to a national agreement but that nothing came from this invitation. All responses to Petro’s speech, with differences in tone, demanded more action and fewer words. CD senator Miguel Uribe, for example, accused Petro of speaking about “dreams and fantasies.”

Year Three: The government’s agenda

The government has an (overly) ambitious legislative agenda for the third year of Congress. This third year is, realistically, the last realistic chance for the government (or anyone) to pass big laws and reforms, given that attention during the fourth year (from July 2025) will be on the 2026 elections.

The labour reform was approved in first debate by the seventh commission of the House, at the last minute in June. It now awaits second debate in the plenary of the House before it makes it way to the Senate. Under the leadership of labour minister Gloria Inés Ramírez, of the most effective ministers in cabinet, the government has been willing to compromise on key points to reach consensus with the Liberals and La U, whose support is needed.

The government has promised that it will present a new ‘consensual’ healthcare reform after the first one suffered a brutal death in April. The government’s new version, yet to be unveiled, comes from a deal with the EPS (insurance providers) but likely lacks the necessary political support in Congress. In addition to the government’s bill, there are three other competing reforms, presented by the CD, the CR and the ‘independent caucus’ (Greens, Dignidad and Nuevo Liberalismo) respectively.

As Petro said in his speech, the government will present a reform to the public utilities law, with the goal of reducing utility rates. Like his other reforms, Petro frames it as changing the neoliberal economic model prevalent since the 1990s, going after the economic interests of big corporations accused of making profits on the backs of consumers. Along with the healthcare reform, it promises to be one of the most contentious and high-profile legislative battles of the next year.

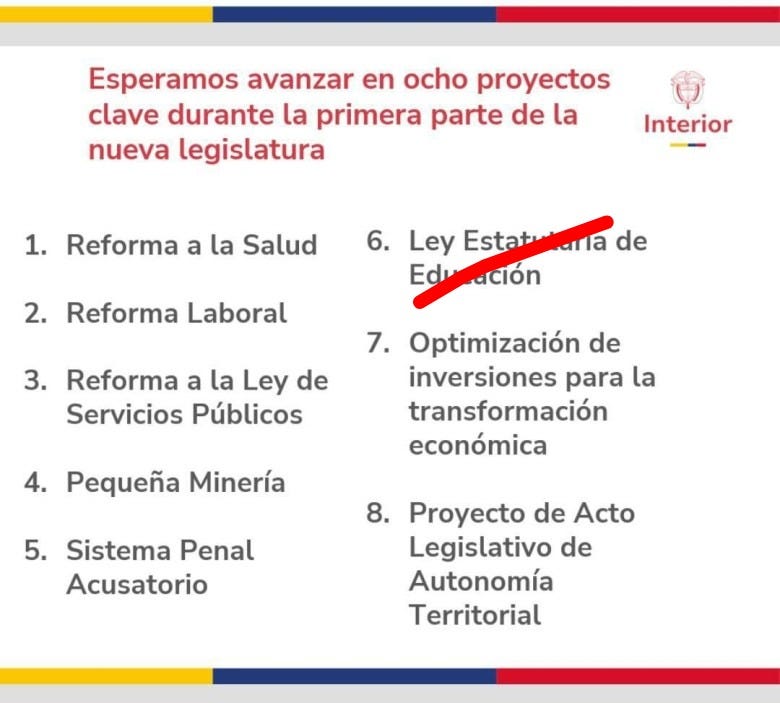

In late July, the interior ministry put out a small graphic listing their eight priorities. It’s been modified since, as Cristo has said on Twitter.

The education reform will not be presented again after it died on June 20.

Cristo has repeatedly said that one priority will be the adoption of the ordinary law for the agrarian jurisdiction, the last step needed for the agrarian jurisdiction to start operating after the statutory law was adopted in June. Cristo has presented it as a key part of the implementation of the peace agreement.

With Cristo as interior minister, accelerating the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement, neglected by Petro over the past two years, has become a new focus for the administration. It’s unclear what will be part of the legislative ‘package’ to speed up the implementation of the peace agreement. Speaking before the UN Security Council in early July, Petro had listed ten points—including agrarian reform (to allow ‘express expropriation’), creating a ‘single system of truth, justice, reparation and reconciliation’ for all actors in the conflict, changing long-term investment rules to fund ‘territorial inclusion’, modifying the transfers system (SGP) to local governments giving more resources to regions affected by violence and illicit crop substitution (releasing incarcerated coca leaf farmers and productive investments in coca-producing regions). Petro had proposed reviving the ‘fast track’ accelerated legislative procedure that’d been used to quickly adopt the necessary laws and constitutional changes to implement the peace agreement in 2016-2017. The politically savvy Cristo, realizing just how unpopular the idea of a new fast track was, quickly buried the idea.

The list of big legislative projects includes the ‘optimization of investments for economic transformation’, which is the government’s nice way of saying ‘forced investments’—compelling private banks to make specific investments in industry, agriculture, housing and tourism. As expected, this idea has proven very unpopular, with hysterical claims that Petro would confiscate individuals’ savings. ‘Forced investments’ already exist in the agriculture sector, and would require banks to buy securities issued by public entities. With most people realizing it was a bad idea, it seems on its way to be quietly dropped by the government, in exchange for a commitment by private banks to open more lines of credit for ‘strategic investments’.

Cristo’s personal mark on the legislative agenda is a constitutional reform for territorial autonomy. Decentralization is one of Cristo’s old personal pet issues, and his party (En Marcha) is already spearheading a constitutional reform that’d double the share of national revenues that’s transferred to local governments and give them more flexibility in how they use that money. This reform could be an opening for an agreement with the right, notably Antioquia’s uribista governor Andrés Julián Rendon, who has forcefully raised debate on the topic.

Not listed on the interior ministry’s graphic but a tax reform for ‘economic reactivation’ (but mostly to pay for the 2025 budget) is undoubtedly going to be one of the big fights of the next few months. It comes as finance minister Ricardo Bonilla is badly wounded from his implication in the UNGRD scandal.

Other, less visible, points on the agenda may include reforms to the mining code (a recurring topic, repeatedly postponed, since 2022) and different bills about criminal justice reform to be presented by the justice minister. Big-ticket items like judicial reform and political-electoral reform don’t seem to be on the agenda.

As always with this government, the legislative agenda is overly ambitious, particularly in the third year of a Congress that hasn’t given the government an easy time. The labour reform was in limbo for months before it finally got approved in first debate, nearly 10 months after it was presented. It took over 9 months for the first healthcare reform to be adopted in its first two debates in the House, before going on to die in the Senate this spring. The healthcare reform 2.0, the labour reform, the public utilities reform and the tax reform—the most important items on the agenda for the government—may take up most of the time and suck up the energy (and political capital) at the expense of other bills.

Managing the legislative agenda will be the big test of Cristo’s skills as interior minister, and whether the acuerdo nacional he’s trying to build amounts to victories in Congress. Cristo’s style is to build as much consensus beforehand, to avoid problems and crises in the actual legislative process later on. We’ll see if his strategy and experience will work for the government.