The Trump-Petro crisis

On January 26, Petro and Trump got their countries into a short diplomatic crisis and trade war over Petro's refusal to accept deportation flights. A look at the crisis and its effects in Colombia.

Less than a week into Donald Trump’s second term, on January 26, Gustavo Petro and Trump got into a diplomatic crisis and trade war that lasted 20 hours, until Petro backed down.

The crisis, even if it was short-lived, spoke volumes about Petro’s leadership and governance style and confirmed a seismic shift in Colombia-US relations under Trump.

20 hours of crisis

Since taking office, the Trump administration has launched large-scale immigration raids and touted deportation flights using military planes. In reality, this is a continuation of what was already happening under the Biden administration, with the added theatrics of using military planes rather than charter flights. According to ICE statistics, 14,200 Colombians were ‘removed’ in FY 2024 and according to data compiled by Thomas Cartwright for the Witness Project, there were 126 deportation flights to Colombia in 2024 (and 139 in 2023).

At 3:40 am on January 26, Gustavo Petro denied permission to US military planes carrying Colombian migrants to land, tweeting that the US cannot treat Colombian migrants as criminals and must establish a protocol for the dignified treatment of deported migrants before Colombia receives them. The day before, the Brazilian government had complained about the ‘degrading treatment’ of deported migrants who landed in Manaus, handcuffed and with their feet restrained. At 9:30 am, Petro shared a news report about Brazil’s complaints and said he’d turned the military planes back. He demanded that they be deported with dignity, in civilian aircrafts, without being treated as criminals. In May 2023, the Petro administration had previously objected to a deportation flight from the US for similar reasons.

Retaliation didn’t take long. Around 11 am, the State Department announced that it would suspend visa processing at the US Embassy in Bogotá. They added that ‘additional retaliatory measures will be implemented soon.’

In the meantime, Petro kept fueling the incipient crisis. He tweeted that 15,660 US citizens living in Colombia illegally should regularize their status with immigration authorities, but he later said that they wouldn’t be deported.

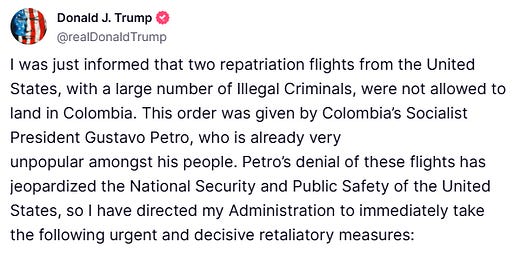

The additional retaliation came from Trump himself, via Truth Social. At 1:30 pm, Trump, calling Petro a ‘socialist president’ who is ‘already very unpopular amongst his people’, announced a series of extraordinarily severe sanctions against Colombia: emergency 25% tariffs on all Colombian goods, to be raised to 50% within a week, a travel ban and visa revocation on Colombian government officials and ‘all allies and supporters’, visa sanctions on ‘party members, family members, and supporters of the Colombian government’, enhanced CBP inspection of all Colombian citizens and cargo on national security grounds, and IEEPA treasury, banking and financial sanctions. The IEEPA sanctions would have allowed Trump to freeze targets’ assets, restrict financial transactions with Colombian banks, block access to the global financial system (IMF, World Bank) and block off the use of US-based credit cards like Visa and Mastercard.

These are the sort of severe sanctions that are usually reserved for the likes of North Korea, Russia, Iran or Venezuela—‘rogue states’ and ‘enemies’ of the United States, not historic allies like Colombia. As I explained in a previous post, Colombia has tended to be the US’ closest ally in Latin America for decades, despite some temporary rifts. The last time a Colombian president had his US visa revoked was Ernesto Samper in 1996, during the Proceso 8.000.

Trump and Petro haven’t interacted much, but there’s natural antipathy between the two men. Trump called Petro a “major loser” during the 2020 campaign, and Petro returned the insult by calling Trump a loser after he lost the 2020 election. Trump is surrounded by staunchly ‘anti-communist’ Florida Republicans, like his new Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who loathe Petro and see him as a dangerous socialist hellbent on turning Colombia into a Cuban-Venezuelan style enemy dictatorship.

Rubio claimed that Petro had previously authorized flights and then cancelled his authorizations when the planes were in the air. Petro denied that he had ever authorized the flights, and that if officials from the foreign ministry had allowed this, it would not have been under his directions. However, at 3 in the morning, Petro had posted (and later deleted) a tweet saying that the migrants would be welcomed back with ‘flags and flowers’.

Trump clearly wanted to make an example out of Petro and Colombia, a clear demonstration to other countries that his immigration policies are not up for discussion and that there’d be dire consequences for any Latin American country that refused to accept deportation flights. Or, as Trump said himself via a AI meme he posted on Truth Social, FAFO.

Just minutes before Trump announced his sanctions against Colombia, the Petro administration had said that the presidential plane would be used to ‘facilitate the dignified return’ of deported compatriots.

The United States is Colombia’s main trading partner, accounting for nearly 26% of exports in 2022 (or $15.6 billion). Colombia’s main exports to the US are crude oil (39%), coffee (11.5%) and cut flowers (10.5%). Two-thirds of cut flowers in the US are imported from Colombia. On the other hand, Colombia accounts for just 1% of US exports. María Claudia Lacouture, the president of the Colombian American Chamber of Commerce, said that the impact of Trump’s tariffs would be immediate and devastating. While Americans would have paid more for Colombian coffee and flowers, Colombia would have suffered the most from the tariffs.

Petro didn’t back down and seemed ready to fight back against Trump, in his own style. He ordered retaliatory tariffs on US goods. At 4:15 pm, he posted a lengthy screed on Twitter (coming it at nearly 700 words), in which he admitted that he doesn’t really like traveling to the US because “it’s a bit boring” although there are ‘meritorious things’—Walt Whitman, Paul Simon and Noam Chomsky, and he likes going to black neighbourhoods in Washington DC, where he once saw a race riot. Addressing Trump, he said he’d be willing to sit down with him to talk frankly about how oil will end the human species through greed, but that it’d be difficult because Trump considers him to be an ‘inferior race’.

In a defiant (and lyrical) tone, replete with references to Colombian and American history (including the Panama Canal, ‘stolen’ from Colombia) and invoking (if not comparing himself to) figures such as Aureliano Buendía (from García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude), Bolívar and Gaitán, he vowed to resist coups (“with your economic strength and arrogance attempt a coup like they did with Allende”) and declared his willingness to die or be overthrown for the cause of Latin American dignity, confident that the Americas would respond if he was killed.

Petro declared that “your blockade doesn’t scare me” because Colombia is “the heart of the world.” Breaking from decades of respice polum (look to the north), he said (in all-caps) that henceforth Colombia would be open to the entire world, with open arms, as builders of freedom, life and humanity.

Many people who only occasionally pay attention to Colombia, whenever the country’s name appears on the frontpage of English-language media, discovered Petro’s rather idiosyncratic writing style and his long-winded social media divagations filled with his mix of pompousness and historical references. However, those who have followed Colombian politics know that Petro, addicted to his Twitter, loves these sorts of long, somewhat cryptic, essays (particularly when he feels threatened or attacked) and that, while he might be a well-read man and charismatic speaker, he doesn’t necessarily put his words into action, and in his political life, he’s always struggled with translating those words into concrete political actions. In other words, Petro’s words may sound defiant, or whatever else, but they may not necessarily mean all that much.

Indeed, while Petro was off somewhere manically tweeting away at Trump, more responsible figures in his government were working through the normal diplomatic channels with the Trump administration. Laura Sarabia, the incoming foreign minister (she took office on January 29), called for calm. Around 10:30 pm, outgoing foreign minister Luis Gilberto Murillo, joined by Sarabia and Colombia’s ambassador to the US Daniel García-Peña, among others, read a statement announcing that the “impasse” with the US government had been overcome. A statement from the White House, claiming total victory, said that the Colombian government had agreed to all of Trump’s terms, including the ‘unrestricted acceptance of all illegal aliens’, including on US military aircraft. The Trump administration stated that the IEEPA tariffs and sanctions would not be signed unless Colombia failed to honour the agreement, and that the visa sanctions and enhanced CBP inspections would remain in effect until the first plane of deportees landed in Colombia. The Colombian government’s statement was more vague about the terms of the agreement, including whether or not it had accepted US military planes.

In the end, Colombian air force planes took off on Monday afternoon, and the first plane landed in Colombia early on Tuesday morning. A bit over 300 migrants have been returned to Colombia since Jan. 29 on three Colombian air force flights. Despite Trump’s constant claims that all the migrants are tough criminals or drug lords, Colombian authorities have stated that none of them have criminal records in either country, and included several children. Interviewed by Colombian media upon their arrival in Bogotá, some of them complained about humiliations and mistreatment by US authorities.

Consular services at the US Embassy in Bogotá finally resumed on January 31. The temporary suspension of visa services had real impacts on people, who had in some cases needed to wait years to get visa appointments at the US Embassy, only to be left out in the cold because of the political fight.

The consequences of Petro’s leadership

Donald Trump twisted the short-lived crisis into a total victory for him, proclaiming the next day that Colombia accepted his conditions ‘almost immediately’. It was an early preview into Trump’s transactional style of ‘diplomacy’, with blackmail and threats for those countries who don’t want to go along. He said so himself the next day, saying that the spat with Colombia had made clear that all countries must receive their ‘criminals, illegal migrants’ or else they’ll pay a very high economic price. A few days later, on January 29, Trump referred to the crisis again, claiming that Colombia ‘apologized profusely’.

In Colombia and abroad, the crisis and its resolution was largely interpreted as a win for Trump and a major defeat for Petro. Several argued that Petro had badly miscalculated and got himself into a fight that he couldn’t really win, or that Petro was quickly hit hard by the political reality.

The crisis also raised even more concerns about Petro’s leadership and governance: the improvisation of foreign policy, the serious consequences of Petro’s impulsive and impetuous tweeting habits, the double-standards and ideological blinders in his foreign policy outlook and his nonchalant disregard for the real-life consequences of his decisions. What Petro was doing tweeting at 3 am on a Sunday also fuels speculation about his messy personal life (with the rumours that he’s drunk, on drugs or was out partying).

As I anticipated last November, “their two personalities (Trump and Petro), not too dissimilar in some ways, are bound to clash.”

The crisis was caused by Petro and Trump’s tendencies for rash decision-making via tweet (and to throw out insults and lash out angrily at critics). It was resolved thanks to the work of diplomats—Murillo, García-Peña and Sarabia on one hand, and Trump’s special envoy for Latin America Mauricio Claver-Carone on the other hand. In an interview the next day, García-Peña confirmed that Petro hadn’t consulted with anyone else before tweeting and celebrated that Petro put the phone down as the taks progressed.

An article in the New York Times indicated that three former presidents, including Álvaro Uribe, offered to help navigate the crisis. Uribe reportedly called Sarabia, offering his help to resolve the crisis despite his differences with Petro, and Sarabia urged Uribe to call his friends in Washington, including Rubio. Uribe offered a somewhat different account of what happened, saying that a third person told him that Sarabia urgently needed to speak with him. He asked for a joint call with the third person who called him, but Sarabia told him that they already had a solution they were working on. The NYT also reported that Republican senators weighed in, urging Trump to show restraint, while members of Petro’s ‘inner circle’ warned of the damage that American sanctions could cause. Murillo told the NYT that Petro was not fully aware of recent changes that allowed military aircraft to be used for deportation flights.

On his side, Gustavo Petro claimed that it was an ‘Colombian uribista’ who asked Trump to sanction Colombia (likely referring to Colombian-born Ohio Republican senator Bernie Moreno, who said he’d introduce legislation to sanction Colombia; Petro also claims that Moreno hates him because of a 1999 congressional debate Petro led denouncing corruption in a bank, which involved Moreno’s family).

The crisis further confirmed the ideological double-standards in Petro’s foreign policy. As Colombian right-wingers were quick to point out, while his government is friends with the ‘tyrant’ Nicolás Maduro, it jeopardized the country’s relations with its closest and strongest ally. While Petro has followed a very cautious (and ambiguous) approach in dealing with Maduro’s Venezuela, with Trump it seemed that ideological animosity came ahead of any diplomatic considerations. Petro suddenly showed concern for the dignity and humanity of migrants, but his administration has been much less receptive towards Venezuelan migrants and has never talked about the discrimination and mistreatment faced by Colombians in Mexico (there have been repeated complaints of xenophobia and mistreatment for years).

As the crisis worsened over the course of Sunday afternoon, Petro showed little concern for the consequences of his (improvised, solitary) decisions—on the economy and the livelihoods of regular people. While Colombia would have suffered the most from a trade war with the US, he ordered, by tweet of course, his ministers to impose retaliatory tariffs, diversify exports and replace US products with domestic products—as if that was quick and easy to do. Instead of showing any empathy for a country panicking about the consequences of the sanctions imposed, Petro preferred grandstanding and a defiant, narcissistic tweet against Trump talking about his disinterest in traveling to the US, reflecting on his favourite aspects of American culture and comparing himself to Allende and Gaitán in anticipation of heroic martyrdom. Tellingly, despite his confidence that the Americas and humanity would respond if he was toppled or killed, only Cuba and Venezuela showed solidarity with Petro. Mexico and Brazil, two ideologically similar governments, didn’t express any support for Petro during the crisis.

The future of Colombia-US relations

In Colombia, Petro’s handling of the brief crisis was likely unpopular and widely criticized by everyone except Petro’s own supporters and political allies.

Unsurprisingly, the right-wing opposition was apoplectic. Álvaro Uribe’s party, the Centro Democrático (CD), in a statement signed by Uribe and the party’s five 2026 presidential pre-candidates, condemned Petro for breaking with the US, the ‘historic ally’, while being allied with ‘the tyranny of Maduro’, and warned that the crisis would destroy the economy. Far-right uribista senator (and 2026 candidate) María Fernanda Cabal, an enthusiastic Trump supporter, furiously tweeted throughout the day, even in English (to call Petro dangerous and mentally deranged), calling on Congress to remove Petro from office. She both insisted that Petro lacked the knowledge or ability to understand his own decisions, and that the crisis with the US was part of a nefarious strategy to distract attention from other failures and impose socialism. Miguel Uribe Turbay, another CD senator and presidential hopeful, called Petro’s decisions were stupid and ideological whims. In various tweets, former Semana director and 2026 candidate Vicky Dávila denounced Petro’s behaviour as clumsy and irresponsible, called him a “megalomaniac, narcissistic, lunatic and very irresponsible president”, denounced how Petro talks smoothly and kneels before criminals but precipitated a crisis with an ally, claimed (without any evidence) that Petro could be plotting to stay in power before celebrating how Trump put him in his place.

The Colombian right, united by an obsessive and quasi-delusional hatred of Petro and eager for a strong leader (but lacking one of their own, for now), has fawned over various right-wing strongmen who have clashed with Petro—Bukele, Milei and now Trump. This crisis will likely just increase their adoration for Trump.

Mayors and governors across the country criticized, in different tones, Petro’s ‘irresponsibility’. Fico Gutiérrez, the right-wing mayor of Medellín, proposed leading a delegation of mayors to meet with Trump, while the uribista governor of Antioquia, Andrés Julián Rendón warned of the grave economic consequences of Petro’s “foolishness, lack of judgement and arrogance.” Alejandro Éder, the mayor of Cali, said that Petro’s management of US relations was unacceptable and complained that the entire population would suffer the consequences of the central government’s bad decisions. In a more measured tone, Bogotá mayor Carlos Fernando Galán called on Petro to act “calmly, sensibly, responsibly”, adding that the crisis should be managed responsibly through diplomatic channels, with the economic interests of the country in mind.

Only petristas and the left sided with Petro. His vice president, Francia Márquez, tweeted that being a migrant doesn’t make one a criminal. Pacto congressmembers, like María José Pizarro, attacked Trump’s arbitrary sanctions against an entire country and called for Colombia’s sovereignty to be respected. Daniel Quintero, the former mayor of Medellín and 2026 hopeful, took a nationalist angle, demanding that Colombia be respected while attacking Vicky Dávila and Cabal for ‘going off to the US every 15 days to speak badly of Colombia’ and those whose hearts are ‘more gringo than Colombian’.

While Sarabia and others in Colombian diplomacy will likely want to steer clear of another fight with Trump, this is not Trump and Petro’s last fight. There are other major troublespots on the horizon: drugs and irregular migration through the Darién gap to name just two. As I wrote back in November, Petro and Trump have diametrically opposed (and conflicting) ideological views and completely different sets of priorities in both their domestic and foreign policy agendas. This crisis and Trump’s freeze in foreign aid will continue to shift Colombia’s foreign policy away from respice polum. This could be good news for China, whose ambassador boasted, in the midst of the crisis, how China and Colombia’s relations are at their best moment. Petro has, until now, hesitated in taking the next step in deepening relations with China, dithering about joining China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Tensions with Trump could push him off the fence.

The fallout of this crisis and the likely tensions in US-Colombia relations are likely to feature prominently in the 2026 presidential campaign. The right (and much of the centre) are likely to push for a return to a closer alignment with the ‘historic ally’, the United States, while the left could take a more nationalist tone, attacking Trump and moving further away from the US.