Trump, Petro: Seismic shift in US-Colombia relations?

Donald Trump’s return to the White House is very bad news for Colombian President Gustavo Petro, and marks an unprecedented, uncharted shift in US-Colombia relations, at least until August 2026.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House is very bad news for Colombian President Gustavo Petro, and marks an unprecedented, uncharted shift in US-Colombia relations, at least until August 2026.

On the morning of November 6, as Trump’s victory was proclaimed, Petro diplomatically congratulated Trump on his victory: “the American people has spoken and it is respected. Congratulations to Trump on his victory.” Underneath the forced formalities, however, it’s a major blow to Petro’s relations with the US and bad news for him.

US-Colombia relations: Respice polum

For decades, Colombia has tended to be the United States’ closest and most consistent ally in South America. A decade or so after the loss of Panama, Marco Fidel Suárez, a foreign minister and later president (1918-1921), coined the term respice polum (follow the north star), which has tended to guide Colombian foreign policy since. Scholars have often described Colombia’s pro-American foreign policy as ‘weak’, ‘subordinated’, ‘dependent’ or ‘introverted’, and more left-wing critics have in the past branded Colombia a client state or puppet of the United States. Colombia’s respice polum foreign policy has endured temporary rifts (Ernesto Samper’s presidency under the clouds of the Proceso 8.000), and some presidents (Alfonso López Michelsen, Belisario Betancur and Juan Manuel Santos, most notably) sought to strengthen and ‘diversify’ Colombia’s diplomacy, while always maintaining close and cordial ties with the superpower. The United States is Colombia’s largest trade and investment partner. The US-Colombia free trade agreement has been in effect since 2012.

Security and the war on drugs have been the central issues in US-Colombia relations since at least the 1960s—and, most of the time, the only topics of real interest to Washington. Under Plan Colombia, the US provided billions in aid to strengthen the Colombian military and fight drug trafficking and insurgent groups. Despite criticisms and the very mixed results of Plan Colombia, it enjoyed bipartisan support across three administrations in the US (Clinton, Bush, Obama) and was often praised as one of the most effective US ‘nation-building’ initiatives in the region. Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) deftly tied his ‘democratic security’ campaign against guerrilla groups to George W. Bush’s global war on terror after 9/11, branding groups like the FARC as ‘narco-terrorists’. This allowed for more flexibility in the use of US aid, to encompass counter-guerrilla (‘anti-terrorist’) operations. In the 2000s, during the peak of the ‘pink/red tide’ in South America, Uribe’s Colombia stood out as a conservative outpost and the Bush administration’s strongest ally in the region. This proximity to the United States contributed to the significant worsening of Colombia’s relations with neigbouring left-wing governments, particularly chavista Venezuela.

Colombian politicians, diplomats and policymakers have often taken pride in saying that relations with the United States are ‘bipartisan’—in that US policy towards Colombia has been supported by both Democrats and Republicans (the main exception being substantial Democratic opposition to the FTA). This has generally been true, although there have been some differences. Democrats have tended to be concerned about human rights, labour conditions and the armed conflict, while Republicans have been more focused about on counternarcotics efforts, security problems, ‘leftist’ guerrilla groups and, more recently, migration and relations with Venezuela.

Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018), whose administration pursued a more active and ‘diversified’ foreign policy, secured widespread support from the international community for the peace process with the FARC and, later, the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. The Obama administration strongly supported the peace process and appointed a special envoy. Obama renamed Plan Colombia, perceived as a militarist war plan, ‘Peace Colombia’ in 2016.

Trump and Colombia

The blunt truth is that Donald Trump knows and cares very little about Colombia. His foreign policy engagement with Latin America is transactional, seeking to make ‘deals’ in which he gets what he wants, and limited to a few issues of interest—migration, crime, drugs and Venezuela.

In his 2019 memoir La batalla por la paz, Santos recounted that in his first phone call with Trump in 2016, the president-elect told him that he loved Colombia because of its ‘good looking women’ and its ‘good workforce and excellent products’. Santos desperately tried to secure Trump’s support for the peace process but Trump had zero interest in it—when it came to Colombia, in his first term, his only concerns were drug trafficking and Venezuela. In the fall of 2017, Trump threatened to decertify Colombia as a partner in the war on drugs because of the “extraordinary” growth of coca cultivation and cocaine production to record levels in 2016. Colombia had been decertified in the 1990s during the Samper administration. In the end, Trump backed down (or was talked out of it by calmer heads).

Iván Duque, deeply pro-American, much more ideologically in sync with Trump and sharing similar priorities, tried to be one of Trump’s friends in South America. Trump, however, showed little affection for Duque and mostly tried to use him and Colombia to further his goals: regime change in Venezuela and the war on drugs. Duque and Trump agreed on those issues: Duque had a staunchly anti-Maduro stance (and was ambiguous about support for US military intervention in Venezuela) and took a traditional prohibitionist approach on drugs, including support for aerial fumigation of coca crops (suspended in 2015, but previously a key aspect of the US-funded war on drugs under Uribe).

Trump was frustrated by Colombia’s difficulties in reducing cocaine production (despite a temporary decline in coca cultivation in 2018-2020, cocaine production potential continued to increase). He pushed Duque to resume aerial fumigation of coca crops, but Duque was unable to do so, despite his best efforts, because of various judicial and other obstacles. In 2019, Trump grumbled that Duque was a “really good guy” but that he’d “done nothing for us” because “more drugs are coming out of Colombia right now than before he was president.”

Uribismo and, indirectly, the Colombian government, interfered in the 2020 election to support Trump. Some uribistas like far-right senator María Fernanda Cabal and Juan David Vélez, representative for Colombian expats and US citizen living in Miami, openly supported Trump—Vélez tweeted ‘WE WILL MAKE COLOMBIA GREAT AGAIN’ in all-caps. Álvaro Uribe himself supported María Elvira Salazar in a congressional race in Florida’s 27th district. Democratic representatives Gregory Meeks and Ruben Gallego denounced Colombian election interference in an article on CNN. Even the US ambassador in Colombia warned Colombian politicians not to get involved in the election.

Trump adopted parts of the uribista playbook to appeal to Hispanic voters in Florida: he tweeted that Biden was a “PUPPET of CASTRO-CHAVISTAS” (castro-chavismo being uribismo’s most time-honoured smear on its opponents for years, imported to Florida by Uribe during the 2016 plebiscite campaign) supported by ‘socialist’ Gustavo Petro, “a major LOSER and former M-19 guerrilla leader,” and claimed that Biden would betray Colombia. The Trump campaign cut a Spanish-language ad, titled Castrochavismo, that notably attacked Biden for receiving Petro’s endorsement. That red scare uribista rhetoric was successful for Trump in Florida, where there were large swings in Trump’s favour among Cuban, Colombian and Venezuelan-American voters in the Miami area.

Juan Manuel Santos claimed that a high-level official in Duque’s government had reached out to help Trump’s campaign and later said that this official was Duque’s ambassador to the US, Uribe’s former vice president Francisco ‘Pacho’ Santos, who allegedly called a Pentagon contractor to ask how he could help Trump. Incidentally, Pacho Santos had already been in the hot seat since late 2019 following leaked audio recordings in which, among other things, he said that the State Department had been ‘destroyed’ under Trump.

After Biden’s victory in 2020, Duque got the cold shoulder from Biden in retribution for Colombian meddling in the election. Duque congratulated Biden on his victory, the foreign ministers talked shortly after the inauguration to reconfirm bilateral cooperation and Biden sent Duque a letter in February 2021 calling Colombia a ‘close and dear country’. However, Duque needed to wait until late June 2021 to get a phone call with Biden, following an attack against Duque’s helicopter. Despite Duque’s desperate efforts to meet with Biden, they only had their first in-person bilateral meeting in March 2022, when Duque was already practically a lame-duck. Biden and Duque’s brief and distant relation was largely based around secondary issues like climate change, Colombia’s support for Venezuelan refugees, Duque’s support for Ukraine and post-COVID recovery. Biden designated Colombia as a major non-NATO ally in 2022.

Petro and the United States

Gustavo Petro has some left-wing Latin American ‘anti-imperialist’ inclinations, and he’s often criticized the US on issues like capitalism, climate change and the drug wars. Unlike Santos and Duque, Petro has never lived or studied in the US and doesn’t speak English. However, he’s pragmatic enough to know the importance of Colombia’s close ties to the United States.

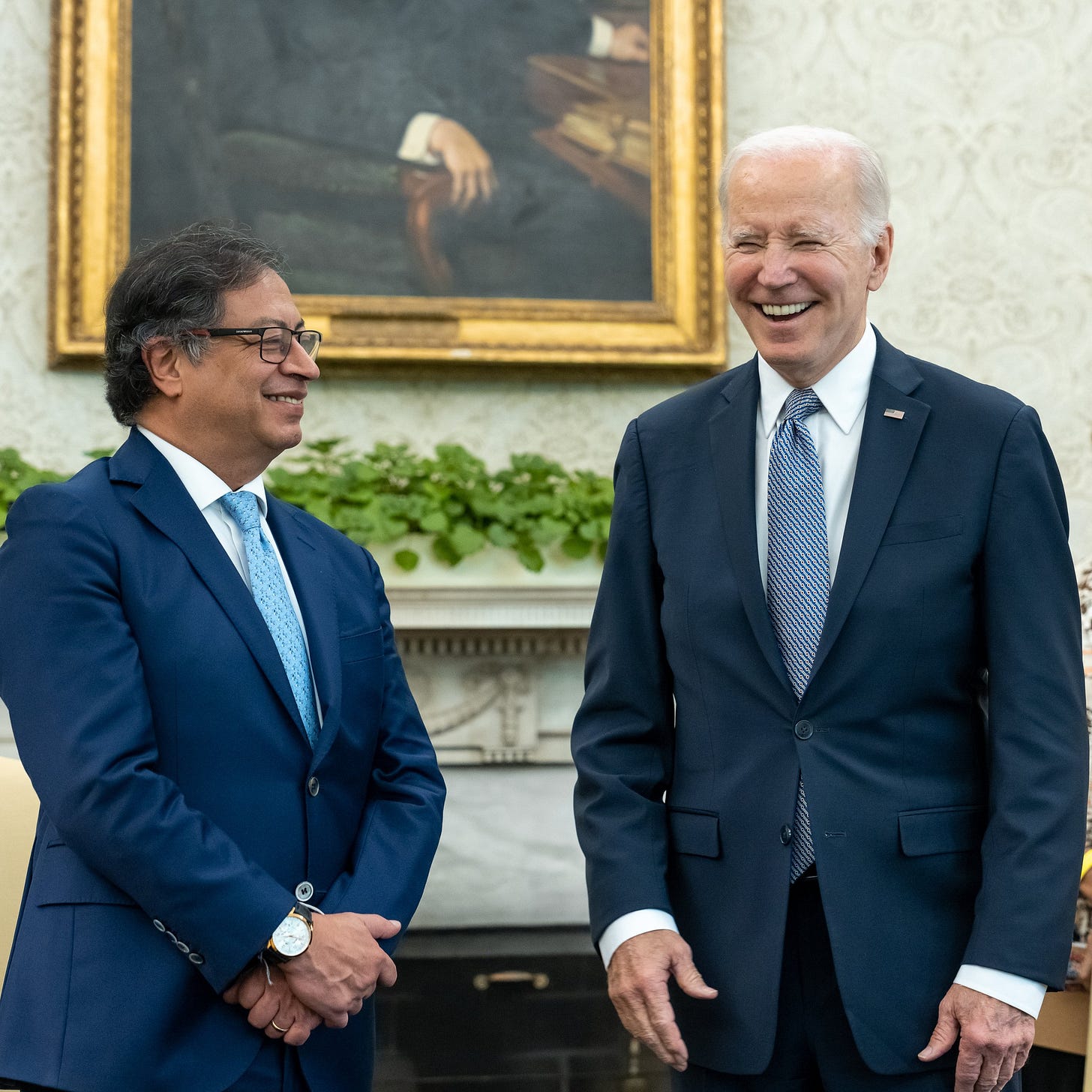

It also helps that Petro supported Biden in 2020 and that Biden welcomed Petro’s victory in 2022. In contrast to Duque, Biden talked with Petro on the phone shortly after his election in June 2022. Petro had his first bilateral meeting with Biden at the White House in April 2023. They discussed climate change, peace, human rights, migration and a ‘holistic’ anti-drugs strategy, and Biden praised Petro for his commitment to fighting climate change and for peace and democracy. Petro found in Biden an ally on topics of shared interest like climate change, labour rights and, to a certain extent, the peace process and a shift away from the old war on drugs approach. Petro and Biden also had a shared interest in finding a political solution to the crisis in Venezuela, but the US quickly lost trust in the Colombian government as a potential facilitator in talks with Maduro.

Petro has chosen respected figures as ambassador to Washington. His first ambassador (2022-2024), now foreign minister, Luis Gilberto Murillo, a centrist politician who had lived and worked several years in the US, was praised as a competent diplomat who built good relations with US politicians, including some Republicans. The current ambassador, Daniel García-Peña, is a US-educated historian and academic who comes from the moderate left and who had previously worked with Petro during his mayoral administration. In contrast, Petro’s first foreign minister (2022-2024), Álvaro Leyva, whose tenure was particularly ineffective and chaotic, was distrusted by US politicians because of some unfortunate remarks.

However, the government has also distanced itself from the US on some important matters, dampening relations with the superpower. Unlike previous Colombian presidents, Petro hasn’t aligned with the US in major global crises: he’s been neutral on the war in Ukraine (he didn’t condemn the Russian invasion and has called for peace, and once said that Russia and the US were the same), he’s repeatedly opposed US sanctions against Venezuela and Cuba (and has often blamed the ‘blockade’ for the crisis in Venezuela) and, most prominently, he has been one of the most vocal international leaders in supporting Palestine and opposing Israel’s war in Gaza, breaking diplomatic relations with Israel in May and accusing Israel of genocide.

Petro has largely avoided explicitly criticizing Biden’s support for Israel, although he’s called on Biden to act to ‘stop the genocide’, stop supporting ‘those who promote barbarism’ and urged the US to establish conditions for a ‘regional peace conference’. Petro’s outspoken views on the conflict, particularly his repeated comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, have been publicly criticized by US government officials like Deborah Lipstadt, Biden’s antisemitism envoy. In September 2024, the US chargé d’affaires at the embassy in Bogotá (Francisco Palmieri) and Lipstadt said that Petro’s comparisons were offensive and that his rhetoric normalized antisemitism. Petro fired back at Lipstadt like he usually does, with a longwinded and abstruse Twitter post, which was translated to English by the foreign ministry.

Petro’s ideological orientations, foreign policy views and the US’ extreme political polarization have threatened the bipartisan consensus over Colombia-US relations. A group of right-wing and staunchly ‘anti-communist’ Cuban-American Republican members of Congress—senators Marco Rubio (FL) and Ted Cruz (TX), and Florida representatives María Elvira Salazar and Mario Díaz-Balart—have regularly attacked Petro’s administration and threatened to cut US aid to Colombia because of Petro’s leftist views and foreign policy stances. In April 2023, Rubio called Petro an ‘agent of chaos’, castigating Petro for courting and cooperating with tyrants and narco-dictators like Maduro and Miguel Díaz-Canel (Cuba), pushing Colombia closer to China and for his ‘total peace’ policy that he predicted would ‘sow disaster’ in Colombia and the region. After Petro’s victory, Rubio’s Senate colleague Ted Cruz, who claimed that Petro was brought to power by Colombia’s ‘leftist fringe’ including terrorist groups, had raised the specter of conditioning aid to Colombia. María Elvira Salazar, one of the loudest opponents of Petro’s foreign and domestic policies in the US, convened a congressional hearing about “Colombia’s descent to socialism” and tweeted that she “completely agreed” with Javier Milei calling Petro an “assassin and terrorist” (the Colombian embassy called on her to respect the dignity of the president’s office).

Mario Díaz-Balart, who met with Petro in April 2023, said that the president’s actions and comments have put the “largely successful U.S.-Colombia relationship in jeopardy”, accusing Petro of sustaining the Maduro regime, partnering with the Cuban regime to facilitate human trafficking and enabling drug trafficking and production. Díaz-Balart, who chairs the House appropriations subcommittee on foreign operations, successfully pushed for a 10% cut is US financial assistance to Colombia in FY2024 ($410 million), conditioned aid to the administration presenting a report to Congress on the state of US-Colombia relations and eliminated Colombia from a list of countries that gets priority in appropriation of funds. He blamed Petro for weakening the ‘special relation’ between Colombia and the US, a view not shared by Murillo, who insisted that the relation remains “solid, robust and bipartisan” and that cooperation is “fundamental” for the entire region. For FY2025, the House has proposed cutting aid to Colombia by 50% (to just $208 million), while the Senate version includes a 10% cut.

Since October 7, Republicans have had even more reasons to attack Petro. Several Republicans in Congress have called Petro a danger to Jews in Colombia, an open anti-Semite or one of the “agents of antisemitism in Latin America” and have repeatedly attacked his refusal to condemn Hamas as a terrorist group and his decision to cut diplomatic ties with Israel in May 2024.

Trump and Petro

Unlike in 2020, Colombia didn’t feature quite as prominently in the US election, probably because Florida wasn’t a swing state.

Petro referred to Trump during a speech he gave in Chicago as part of his trip to the US in September for the UNGA—incidentally, he narcissistically self-promoted that speech as “the best speech of my life.” Talking about the ‘Haitians eating dogs in Springfield’ hoax, Petro called Trump racist, xenophobic and a terrorist (bizarrely, it appeared that Petro’s main problem with that hoax wasn’t as much the racism but that he too was a victim of such manipulations). Trump only mentioned Colombia six times, often in passing, during the campaign, almost always as an example of ‘criminal migrants’.

Trump’s second term is bad news for Petro, and could portend a seismic shift in US-Colombia relations, at least until August 2026. Petro will have a very hard time working with Trump until his term ends in August 2026. Thus far, he’s tried to put a brave face on it, commenting that Trump would have his full support if he ‘ends wars rather than starts wars’ and naively trying to set the agenda, insisting that north/south dialogue is still in force. In his congratulatory tweet, Petro alluded to Trump’s anti-immigration views (“the only way to seal the borders is with the prosperity of the peoples of the south and the end of the blockades”).

We can predict that Trump’s interest in Colombia will remain very limited and he’ll only care about insofar as it relates to a few key issues for him: drugs, migration and potentially Venezuela.

Trump will have basically no interest in climate change, which has been one of the cornerstones of Petro’s foreign policy and a personal priority for Petro.

Drugs: Clashing visions

Petro wants to change the paradigm on drug policy, away from criminalization and the war on drugs towards a public health and human rights approach. Colombia’s 2023 drug policy aims to address the structural causes of the problem and shifts repressive focus away from the lower echelons of the drug supply chain (coca cultivators) towards the large, lucrative criminal drug trafficking and money laundering networks. Translating ambitious and laudable ideas into reality has, unsurprisingly, been very difficult.

According to the latest UNODC report, coca cultivation in 2023 increased by 10% to a record high 253,000 hectares, while cocaine production potential exploded by 53% to 2,664 tons a year. Coca cultivation has increased from 142,700 ha. in 2020 (the lowest point in a brief reduction in coca cultivation from 2018 to 2020) and 204,000 ha. in 2021. Petro has taken a much more permissive stance towards coca cultivation, recognizing the alternative uses of coca (a longstanding demand of cultivators and communities) and redirected military and institutional efforts towards interdiction (drug seizures) or forced eradication of ‘industrial-size’ coca plantations. The government argues, for good reason, that eradication, the traditional measure of ‘success’, is very ineffective. According to defence ministry numbers, only 20,323 hectares were manually eradicated in 2023, down from over 100,000 hectares a year in 2020 and 2021 under Duque (and it will fall even lower in 2024, just 4,504 ha. in the first nine months of 2024). On the other hand, the government has regularly trumpeted (particularly to the US) record-high cocaine seizures: 746.3 tons in 2023, over 683 tons in the first nine months of 2024. However, experts point out that seizures are going up at the same rate as cocaine production.

The Biden administration, despite some private qualms, took a permissive approach, not interfering with Colombia’s drug policy and routinely re-certifying Colombia as a partner and renewing a drug interdiction assistance program. Petro’s GOP critics regularly called on Biden to decertify Colombia for failing to cooperate with US counternarcotics efforts and pounded on Biden for quietly suspending satellite monitoring of Colombian coca crops.

Given how Trump complained about Colombia’s drug problems under a very friendly president like Duque, he’ll certainly be infuriated by Petro’s drug policy (once he finds out about it). There is a very real possibility that Trump will decertify Colombia (as he threatened to do in 2017, under Santos, who criticized the failure of the war on drugs but remained reliably aligned on US policy otherwise), drastically cut aid to Colombia or forcibly demand that Petro reduces cocaine production or increases eradication. Petro’s poor record on both indicators could easily be read by Trump as proof that the US is again being ‘ripped off’ and ‘played for a fool’ by a ‘socialist’. The GOP House’s moves to cut and condition aid to Colombia, and their open hostility to Petro, foreshadows what’s likely to happen. In his transactional mindset, Trump will demand a lot from Petro, and it’s unlikely that Petro will even want to comply with these demands given his own views.

The US-Colombia security relationship goes much deeper than just drugs, as Colombian presidents have regularly sought to impress upon US policymakers, but Trump has little interest in those complexities. Petro’s total peace policy is already largely a failure on its own, but Trump is highly unlikely to look favourably upon it.

Migration

The other issue where Trump will certainly push Petro hard is on migration. Since 2021, the infamous Darién Gap, the most dangerous jungle in the world on the border between Colombia and Panama, has become the immigration bottleneck of the Americas. In 2023, a record-high 520,000 migrants crossed, although in 2024 that number will be lower, but still higher than in previous years—286,200 people had crossed in the first ten months of this year. The vast majority of migrants come from Venezuela (nearly 330,000 in 2023), as well as Ecuador, Haiti and Colombia but also China, Afghanistan and sub-Saharan Africa, most hoping to make their way to the US’ southern border.

The unprecedented number of crossings through the treacherous jungle has created a major humanitarian crisis in Colombia and Panama. In the Darién Gap, migrants face not only the natural dangers of one of the most inhospitable jungles in the world but also threats from the criminal groups that reign over a region where state presence is very weak. The Colombian side of the border is controlled by the Clan del Golfo, Colombia’s largest organized criminal group and drug trafficking network. They control drug trafficking routes through the region and oversee a lucrative migrant smuggling racket, receiving a share of the money charged by the ‘guides’ or migrant smugglers (coyotes)—HRW estimates that the Clan gets $125 for each migrant. Local gangs on the Panamanian side pose a more obvious threat to the thousands of migrants passing through, who’ve faced assault, rape and robbery. Hundreds of migrants have died or disappeared in recent years, and little humanitarian assistance is available on either side.

The Darién crisis is a hot potato thrown around between Colombia, Panama and the United States. Essentially, Colombia, a transit country, wants to get rid of migrants (at best, manage their orderly transit through the country), Panama doesn’t want to receive them and would like to close the border, and the US has a vested interest in Colombia and Panama working together to retain as many migrants as possible so that they don’t end up at the US border. In spite of the usual grandiloquent progressive rhetoric on the topic, migration hasn’t been a priority for the Petro administration. Petro supports the ‘voluntary return’ of Venezuelan migrants, in tacit agreement with Maduro’s repatriation plan, and Venezuelans have faced problems and obstacles in regularizing their status and their integration. In September 2023, Petro falsely claimed that US officials had proposed building a wall in the Darién, which the US later denied. Murillo later said that Petro was speaking about walls in a figurative sense.

The Darién crisis has led to diplomatic tensions with Panama, which has implicitly accused Colombia of turning its back to the problem, criticizing Colombia for the lack of migrant screening and for weak border controls. Panama’s new president, José Raúl Mulino, campaigned on a promise to close the Darién route; in practice this has translated to closing unauthorize routes and a deal for the US to cover the costs of repatriating illegal migrants.

The Biden administration has attempted to slow the flow, by creating new legal pathways for migrants to apply for admittance to the US as refugees and trying to keep as many of those migrants from making the journey north to the US—“don’t come”, as Kamala Harris said in Guatemala in 2021. In 2023, as part of its ‘safe mobility initiative’, the US opened migrant processing offices in Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Guatemala. The offices in Colombia an handle applications from Cubans, Haitians and Venezuelans with legal status in Colombia by June 2023. In April 2023, Colombia, Panama and the US announced a joint campaign to fight the illegal flows of goods and people, provide alternative legal pathways for migration, and reduce poverty and create jobs in border communities. Previously, Colombia and Panama had announced a ‘roadmap’ with commitments to increase binational operations, improve information sharing, coordinate efforts and open dialogues with countries of origin.

The Petro administration has opened peace talks with the Clan del Golfo as part of his paz total policy, but the process has had several ups and downs, including a short-lived ceasefire in 2023, and negotiations will be difficult. The Clan del Golfo has included migration among the major topics it wishes to discuss with the government and the US.

Donald Trump will have a huge impact on the migration crisis in South America. The impacts of his plans for mass deportations, suspension of refugee resettlement, reducing of legal immigration and ending TPS for Venezuelans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and others will be felt in Colombia and other countries. Trump, combined with the continued political crisis in Venezuela after Maduro’s fraudulent ‘reelection’ this summer could lead to another spike in migration to Colombia.

Trump’s few mentions of Colombia during the 2024 campaign were mostly related to migration (and migrant criminality). He will likely put heavy pressure, backed up by threats, on Petro to reduce migration flows from Colombia through the Darién Gap and other routes.

Shifts in US-Colombia relations

Donald Trump is used to make policy by tweet, react erratically and lash out angrily at criticism. In a way, so is Gustavo Petro. Their two personalities, not too dissimilar in some ways, are bound to clash. Petro may call Trump a fascist or a racist on Twitter or in a speech, which may get noticed by Trump and spark an angry reaction from him.

There will be obvious, natural tensions in US-Colombia relations, at least until Petro’s term ends in August 2026. The US and Colombian presidents will have diametrically opposed (and conflicting) ideological views and completely different sets of priorities in both their domestic and foreign policy agendas—something that hasn’t happened much, if at all, in recent decades (in fact, both countries’ presidents were usually ideologically in sync most of the time: Uribe-Bush, Santos-Obama, Duque-Trump).

Trump’s pick for Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, is likely making the Colombian government very nervous. Rubio knows about and is interested by Colombia, but has a very right-wing conservative bias in his reading of the country’s politics, thanks to his longstanding close ties to the very uribista Colombian-American community in Miami. As mentioned above, Rubio’s comments about Petro have never been kind: he’s been particularly critical of Petro’s anti-Israel stances (which he considered an ‘absolutely shameful’, his ties to Maduro and the peace negotiations with the ELN; he’s also accused Petro’s ‘weak’ and ‘failed’ policies of destabilizing Colombia and neighbouring countries and fueling drug trafficking. If the Petro administration may have hoped that Trump would ‘forget’ about Colombia, Rubio’s nomination indicates that Colombia and Latin America will be, if not a priority, at least of interest to the new US administration and State Department.

This will almost certainly continue to shift Colombia’s foreign policy away from respice polum—again, at least until 2026. Under both Duque and Petro, Colombia’s diplomatic and economic ties with China have deepened quite significantly, but both presidents have hesitated when it comes to ‘taking the next step’ in aligning more closely with China. China is already one of the top importers in Colombia and Chinese companies are building key infrastructure projects, most notably the Bogotá metro. Duque and Petro both visited China (in 2019 and 2023 respectively), and Murillo visited last month. On the occasion of Petro’s visit in 2023, China upgraded its ties to Colombia to ‘strategic partnership’ level, the last South American country to acquire this status (except for Guyana). China has invited Colombia to join the Belt and Road Initiative (Colombia is the only South American country besides Brazil and Paraguay that isn’t a member), and Murillo announced the creation of a working group to negotiate conditions to join the Chinese initiative and resolve unspecified ‘contentious issues’. Petro has hesitated to further align politically and diplomatically with China. His 2023 visit was largely a waste, with Petro’s focus going there being his very parochial obsession with the Bogotá metro (he said he’d talk to Xi Jinping about his stubborn demand for the metro to be underground).

A Trump-led US that’s even more disinterested in Latin America, and tensions and disagreements between Petro and Trump, may push Petro closer to China. Already under Biden, Petro was shifting away from the respice polum doctrine towards a multipolar foreign policy. Trump may accelerate it. With an openly hostile administration in the US, Petro may find a much friendlier partner in China.

The Colombian right celebrates

Gustavo Petro will be replaced by a new president in August 2026. Given Petro’s unpopularity and petrismo’s current difficulties in finding a strong candidate, there’s a strong possibility that the right will return to power in Colombia in 2026. Trump’s victory makes them even more hopeful that whatever ‘wave’ carried Trump to power again this year will continue until 2026, and sweep the petrista left out of office in Colombia.

While Petro and the left may be despondent and nervous about Trump’s second term, the Colombian right is quite upbeat. The right-wing opposition has often claimed that Petro’s foreign policy is isolating Colombia from its traditional allies like the United States.

Uribista senator and presidential candidate María Fernanda Cabal, Trump’s biggest fan in Colombia, posted an adulatory letter to Trump, saying that MAGA “serves as a guiding light for our own mission to secure the presidency in Colombia and protect our nation from the encroaching threat of communism.” Her colleague and fellow presidential hopeful, Paloma Valencia, said that Trump’s election was an “enormous hope” for the entire world because of his decision not to endorse future wars and a victory for freedom of speech. Álvaro Uribe congratulated Trump, hailing him as an “example of tenacity and the ability to reach all economic and social sectors of the community”, and said Colombia must “strengthen its historic relationship with the United States on all issues.”

Finally, Semana’s Vicky Dávila, the right’s putative frontrunner for 2026, posted that the wave of ‘democracy, freedom, family and prosperity’ that the Trump wave will reach Colombia in 2026. Incidentally, perhaps taking advantage of the Trump victory, on November 16 Dávila announced her resignation from Semana and effectively announced her presidential candidacy after months of speculation.

If the Colombian right returns to power in 2026, they’ll get along great with Trump, who has increasingly become a new idol for them. This could reorient Colombian foreign policy towards the more traditional respice polum.