Petro's cabinet shuffle

President Petro reshuffled his cabinet, bringing in six new ministers in important portfolios. A look at the new faces & what they mean for Petro's administration.

President Gustavo Petro has completed his third major cabinet shuffle. Over 12 days, slowly and via Twitter, Petro dismissed and replaced six cabinet ministers. Petro’s administration has been characterized by very high turnover. In two years in power, Petro has had 38 ministers in 19 ministries—roughly the same number Iván Duque had in four years. His ministers have, on average, lasted only 8 months in their job. Following this shuffle, there are only three ministers left from the original cabinet—the defence, labour and environment ministers, plus Vice President Francia Márquez as equality minister. The ministries of the interior, education, agriculture, culture, transport and sports have now had three ministers in two years.

Let’s take a look at the latest shuffle and what Petro’s choices mean for year three.

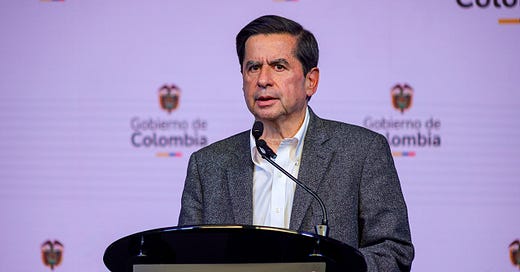

Interior: Juan Fernando Cristo

Perhaps the biggest change of the shuffle was the new interior minister, Juan Fernando Cristo, replacing Luis Fernando Velasco.

Velasco had been interior minister since May 2023 and was worn out. Interior minister, the most ‘political’ of all portfolios, is a thankless job, particularly when dealing with weak majorities in Congress and a mercurial president. Velasco had a difficult and rocky term, with great difficulties at getting the government’s legislative agenda through Congress in year two. He was severely weakened by his implication in the UNGRD scandal. Petro confirmed that Velasco was leaving the government via tweet on June 29, and on July 3 he announced his successor, Juan Fernando Cristo, after intense media speculation and rumours.

Cristo is a seasoned politician, a former Liberal, who served 16 years in the Senate, from 1998 to 2014, and who’d already been interior minister, during Juan Manuel Santos’ second term, from 2014 to 2017. Born in Cúcuta (Norte de Santander), Cristo is the son of a Liberal politician, Jorge Cristo, who was assassinated by the ELN in 1997. Cristo, who had held public office since 1990 (including as President Ernesto Samper’s communications adviser and ambassador to Greece), ‘inherited’ his father’s seat in 1998. With his stronghold in Norte de Santander, he held his seat for four terms, and was one of the Liberal Party’s most prominent senators, in opposition to Álvaro Uribe. As senator, he was the leading advocate for the victims’ law, which was finally adopted in 2011 during Santos’ first term. In his final term in the Senate, Cristo was president of the Senate (2013-2014). He didn’t seek reelection in 2014, leaving the seat to his brother, Andrés Cristo, and played a key role in Santos’ reelection campaign. Cristo was interior minister for much of Santos’ second term, and was behind the ‘balance of power’ political reform of 2015 (which, among other things, eliminated presidential reelection) and oversaw a series of legal changes that cleared the way for the 2016 peace agreement. After the peace agreement was finally sealed and adopted in late 2016, Cristo was responsible for its early implementation in Congress, through the so-called special ‘fast track’ procedure. As Santos’ interior minister, Cristo also managed the infamous mermelada (patronage appointments and pork-barrel spending) and the computador de Palacio (‘database’ of bureaucratic concessions, quotas and patronage) that kept Santos’ coalition together.

Cristo resigned in May 2017 to run for the Liberal presidential nomination, but was defeated in the Liberal primary in November 2017 by Humberto de la Calle. In conflict with Liberal boss César Gaviria and in disagreement with the party’s support for Iván Duque’s new government, Cristo quit the Liberal Party in late 2018. He created his own political movement, En Marcha, envisioned as a centrist progressive movement (and posing as ‘alternative’ despite Cristo’s career as a traditional politician). En Marcha won three seats in the Senate in 2022 as part of the Centro Esperanza centrist coalition, and supported Sergio Fajardo in the first round. In the second round, Cristo and his movement endorsed Petro. En Marcha has been ambiguous about its stance vis-à-vis the government, declaring itself ‘in independence’ in 2023. En Marcha obtained legal party status in November 2022 as part of the CNE’s festival of parties, but the Council of State overturned the CNE’s decision in May. Cristo and his senators have been a small but somewhat sizable swing bloc in making or breaking the government’s majorities in the Senate. According to La Silla Vacía, Petro called Cristo personally to offer him the job and Cristo himself later said that they talked ‘for hours’ about their agreements and disagreements before he accepted Petro’s offer.

Cristo’s appointment shows that Petro wants an experienced hand who knows the intricacies of politics and congressional negotiations to move his agenda through Congress in year three (likely the last chance to get substantial reforms adopted). It’s also a sign of relative openness to Congress and the rest of the political class, given Cristo’s experience and cordial ties with other political sectors, notably the centre. However, Cristo’s room for manoeuvre may be limited, given Laura Sarabia’s power and influence.

Following his appointment, Cristo listed his four key objectives as interior minister. The one that got the most attention and sparked the most controversy and debate was the constituent assembly, which has haunted the political debate ever since Petro raised it on March 15. At the time, Cristo said that a constituent assembly was a bad and unviable idea. On July 3, Cristo said that his first task as minister will be to seek a ‘national agreement’ (acuerdo nacional), with all political groups and institutions, that would “consider the possibility of convening a national constituent assembly under the parametres of the 1991 constitution.” This potential constituyente would be convened and elected during the next presidential term—that is, after 2026. Cristo’s statement clarified the idea of a constituent assembly, after Petro had spent months diluting the idea with terms like ‘constituent power’, but also made clear that it would be convened under the procedure set out in the 1991 constitutent (rather than by decree, as some Petro loyalists had suggested, or by unilateral referendum) and would only be elected after 2026. The idea could become one of the big issues in the 2026 elections.

Cristo’s comments ignited a firestorm of contoversy. José Fernando Reyes, the president of the Constitutional Court, indirectly criticized the idea, saying that the constitution could not be a “gelatinous, deformed mass changeable at will.” Álvaro Uribe tweeted that a constituent assembly would lead to years of constitutional uncertainty, when Colombia needs jobs and security. In a video, Juan Manuel Santos said that a constituent assembly is “inconvenient, unnecessary and going down a dead-end road,” “the last thing the country needs,” and instead urged the administration to focus on the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. Alejandro Gaviria, Petro’s former education minister (2022-2023) who was the leading figure of the ‘centrist liberals’ in the first cabinet, wrote that the constituent assembly would lead to greater political confrontation and leave major problems unattended. Several former ministers, former members of the 1991 constituent assembly and other retired politicians of different political persuasions signed two letters, both rejecting a possible constituent assembly. Only Germán Vargas Lleras, who has called Petro’s bluff since March and is playing 3D chess (alone), welcomed Cristo’s comments and urged the government to speed up the process.

The mythical acuerdo nacional that Cristo makes the sine qua non for a future constituent assembly has been mentioned countless times since Petro’s election in 2022. At different times, the government seemed to make conciliatory moves in that direction, meeting with opposition politicians, business leaders or the other branches of government. Two years later, nothing tangible has come out of these various small steps towards an acuerdo nacional, in good part because of Petro’s temperament and unwillingness to compromise.

While Cristo does seem to be genuinely committed to the principle of an acuerdo nacional, it’s not clear if Petro is fully onboard. Without consulting anyone, Petro quickly tweeted his own list of nine topics that should be part of a national agreement (it’s unclear why any of these issues would require a constituent assembly), but diluted his new minister’s statement by again mentioning the ‘constituent power’. Since March, Petro has sought to use the spectre of the constituent assembly as a means to foment popular agitation in favour of his administration and its reforms, against the ‘oligarchy’ and the ‘establishment’ accused of blocking his agenda. Cristo’s acuerdo nacional is presented as something that would be the result of negotiations with all political sectors, and may conclude around an understanding that the 1991 constitution needs to be reformed through a constituent assembly. Petro’s acuerdo nacional often seems to be based on the idea that everyone else will agree with him on his predefined list of topics, and that a constituent assembly is inevitable for various reasons (alleged ‘counter-reforms’ to the constitution, Congress’ inability to fully implement the constitution, and new circumstances and issues like the climate crisis make it necessary).

Cristo’s other three objectives are the legislative agenda of the government in Congress in 2024-25, the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement with the FARC and deepening territorial autonomy and fiscal decentralization. Managing the administration’s legislative agenda is the main ‘routine’ task of the interior minister, and I’ll discuss it more in a separate post about year three in Congress.

Cristo as interior minister signals a greater commitment by Petro to be serious about the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. Petro has regularly criticized the implementation of the peace agreement and said that it is incomplete or doomed to fail, but at the same time his administration has largely neglected its proper implementation (like Duque before him). Cristo was one of the political and legal architects of the 2016 peace agreement and it has remained one of his key political causes over the past years. He’s promised a plan de choque for implementation over the next two years.

On July 11, at a long-anticipated address before the UN Security Council about the peace agreement, Petro proposed the idea of reviving the ‘fast-track’ accelerated legislative procedure to speed up the adoption of legislation to implement the peace agreement, specifically mentioning about eight points. The ‘fast-track’ was a special, temporary, legislative process adopted in 2016, designed to rapidly adopt necessary constitutional amendments and laws specifically to implement the peace agreement, speeding up the normal legislative process . Realizing how unpopular the idea was among congressmen (and how unlikely it was to happen), Cristo quickly buried the idea—first saying it was only a ‘draft’ idea and later saying that there could be other means.

Territorial autonomy and decentralization are Cristo’s personal pet issues. En Marcha’s senators have presented a constitutional amendment that’d double the share of national revenues that is transferred to departments and municipalities and give local governments more flexibility in how they use that money (the bulk of it is currently earmarked); this reform is about halfway to the finish line. Petro has occasionally raised the issue of reforming Colombia’s territorial organization and deepening decentralization, but at other times he’s behaved in very centralizing ways with little regard for local governments. This issue, however, could also be Cristo’s way to build understanding with other political leaders, for example Antioquia’s uribista governor (and right-wing rising star) Andrés Julián Rendon, who has raised debate on the issue with his proposal to organize a referendum to increase department’s fiscal autonomy.

Justice: Angela María Buitrago

As had been expected, justice minister Néstor Osuna left cabinet—he had wanted to leave—and he was replaced by Angela María Buitrago, a criminal lawyer and former prosecutor who had been one of the three women on Petro’s shortlist for attorney general. I wrote a brief profile about Buitrago here, copied and edited below.

Buitrago, a criminal lawyer, was a prosecutor before the Supreme Court from 2005 to 2010, responsible for investigating important cases like the siege of the Palace of Justice in 1985 (indicting and convicting senior military commanders) and cases against several public figures including former governors, congressmen and ex-prosecutors. In 2010, she was dismissed by caretaker attorney general Guillermo Mendoza Diago, ostensibly because she was ineffective, or perhaps because she was too effective at stepping on powerful people’s toes. In an interview, Buitrago later said that there was “sabre rattling from political and military sectors” asking for her head. After leaving the Fiscalía, Buitrago has been a law professor at her alma mater, the Universidad Externado, a member of the interdisciplinary group of independent experts for the Ayotzinapa case in Mexico, and a member of the UNHRC group of human rights experts on Nicaragua. Buitrago was one of the three names on Petro’s shortlist of candidates for attorney general, presented in August 2023. In March 2024, the Supreme Court elected Luz Adriana Camargo as attorney general; Buitrago, who had not ‘campaigned’ for the job, received two votes in the fourth and final round.

Néstor Osuna struggled to leave much of a lasting legacy from his term as justice minister, but he can point to the presentation of Colombia’s new drug policy and the adoption of the statutory law for the new agrarian jurisdiction. In the first half of 2023, his criminal-prison reform and a surrender to justice proposal (critical for Petro’s ‘total peace’ policy) both died in commission, not even reaching first debate. He struggled to deal with long-term problems in the country’s judicial system, most notably the prison crisis (in February 2024, the government declared a prison emergency in response to the murder of several prison guards). Osuna was tired and worn out of the job, but his name has also come up as a potential candidate for ombudsman (Petro must select three nominees for the office, to be elected by the House).

Buitrago’s main priority will be finalizing and presenting judicial reform proposals before Congress. At the beginning of the year, the government created an expert commission on judicial reform, made up of a diverse group of judges, union leaders, experts and politicians—including opponents like former Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras. Petro’s constituent assembly proposal (which includes judicial reform and truth and reconciliation as one of its points) has cut the ground from under their feet and undermined Osuna’s efforts. Buitrago has said that the government intends to present three proposals shortly, dealing with the prison system, criminal procedure and drug policy. The government appears unwilling to embark upon a long, difficult judicial reform that’d deal with the high courts’ powers.

Agriculture: Martha Carvajalino

Petro dismissed agriculture minister Jhenifer Mojica and replaced her with Martha Carvajalino, who had been vice minister of rural development.

Mojica had been minister since April 2023. Petro had grown increasingly frustrated and unhappy with her performance, particularly the glacial pace of the agrarian reform, one of Petro’s main objectives. She was also in the hot seat because of her ministry’s low budget execution numbers: 91% in 2023, 44.5% by June 2024. Her ministry’s poor performance indicators had also earned her the enmity of Alexander López, the new national planning director who has become Petro’s eyes to monitor his ministers. Mojica needed to defend herself publicly, tweeting that some wanted to tarnish her performance by saying that the ministry had low budget execution.

Mojica has also been embroiled in a spat with Gerardo Vega, the former director of the National Land Agency (ANT), the agency responsible for buying land for the agrarian reform. The ministry and the ANT had presented contradictory numbers on agrarian reforms, with Vega falsely claiming that the government had formalized 1 million hectares of land, by misreporting information (the administration had only formalized 120,900 ha of land) and the ANT. Using the ANT’s numbers, the first edition of the government’s official newspaper Vida said that the administration had bought 230,000 hectares of land, when the ministry’s ‘counter’ only reports the purchase of 88,155 hectares. Mojica also opposed Vega’s risky mechanisms to buy land.

Martha Carvajalino has a similar background to her predecessor: she’s a lawyer, graduate of the Universidad Nacional, expert on agrarian issues and spatial planning, and previously worked in the Procuraduría (responsible for environmental and agricultural issues). She was vice minister of rural development from June 2023 to January 2024, under Mojica, responsible for the reactivation of the national system for agrarian reform (a system to coordinate the actions of different ministries and agencies in the agricultural sector).

Petro tweeted that she would “promote the agrarian reform and a productive countryside with social justice.” That’s a huge challenge given the difficulties in meeting the government’s stated objectives (distribute 1.5 million hectares of land, revised downwards by half from 3 million hectares), as Petro himself admitted that his government would have trouble reaching even 500,000 hectares by 2026. The agrarian reform is stalled, despite a 125% increase in the agriculture sector’s budget in 2024, because of the lengthy, complicated, costly and excruciatingly slow process of voluntary land purchases—the government’s main strategy, given that expropriation (despite being perfectly legal) is taboo in Colombia (and Petro made a notarized campaign promise not to expropriate land). The government has tried to find various ways to speed up procedures for land purchase or to distribute land (like redistributing land seized from paramilitaries and criminals). Very little progress has been achieved on the government’s original big gambit—purchasing, at market values, 3 million hectares of land from Fedegán, the national cattle ranchers’ federation (at a huge price tag, estimated at 60 trillion pesos by Petro). So far, Fedegán has offered 1,400 properties of 600,000 ha in all but the government has only purchased 33 properties of 10,300 ha.

Education: Daniel Rojas

Petro dismissed education minister Aurora Vergara and replaced her with Daniel Rojas.

Vergara, who is close to Vice President Francia Márquez, had been education minister since February 2023, replacing Alejandro Gaviria. Petro had been unhappy with her for several months already, annoyed by the lack of progress on the construction of the 26 new public university campuses announced by the administration. Petro reportedly called her ‘incompetent’ at a cabinet ‘conclave’ in late December, and at an event that month, without naming her, he publicly expressed frustration with bureaucrats who needed to be pushed to implement his education agenda. Her position, however, became even more unsustainable following the controversies surrounding the selection of the new rector of the National University, and, more importantly, the debacle of the education reform in June.

The education reform initially seemed to be sailing smoothly, but ended up collapsing after the government struck a deal with opposition parties in the Senate which triggered a strike by Fecode, the powerful teachers’ union (a key ally of the left). The government gave in to Fecode and broke its deal with the opposition. With no time or consensus left, the government was forced to let the reform die at the end of the last congressional sessions on June 20. Petro blamed the opposition for the fiasco, but he didn’t bother to come to his minister’s defence. Vergara, under fire from all sides (the opposition, the unions, the governing coalition, her own colleagues) for her calamitous mismanagement of the reform, desperately held out hope that the reform could be salvaged and insisted that she would not resign and would present the reform again. Petro had other ideas.

The new minister, Daniel Rojas, was one of the biggest surprises of the shuffle but also the most controversial appointment. Rojas, who had been director of the Sociedad de Activos Especiales (Special Assets Society, SAE) since 2022, is a young economist and left-wing activist—and one of Petro’s closest allies and confidantes. Rojas, born in 1987, first met Petro in 2011 and actively participated in Petro’s mayoral campaign in Bogotá that year. During Petro’s mayoralty, he worked for the city, supporting youth programs. Rojas participated in Petro’s presidential campaigns in 2018 and 2022, serving as platform coordinator on economic matters in 2022. After Petro’s victory, he was part of the transition team. Rojas was appointed to head the SAE, the agency responsible for managing seized assets. The SAE has been a ‘nest’ of corruption for several years, with several irregularities in the management of seized assets and corruption scandals, which have continued under this administration. As head of the SAE, Rojas focused on turning over the assets managed by the agency to the communities—for example, 69 properties will be given to twelve public universities and properties that formerly belonged to the mafia were transferred to peasants and social organizations. The SAE has become an important part of the government’s agrarian reform efforts.

Rojas was suspended from office for three months by the Procuraduría in February 2023 for halting the sale of shares in Triple A (Barranquilla’s troubled public utilities company) to K-Yena SAS, a company owned by the city (i.e. the Char clan) and the wealthy ‘czar’ of the trash collection business William Vélez. Rojas’ reasons for halting the sale were quite valid (including that the shares were greatly undervalued when the deal was made in 2021) and the Procuraduría’s decision was criticized and raised questions about the real motivations behind it given Inspector General Margarita Cabello’s close ties to the Char clan. His suspension was lifted after the SAE agreed to release the shares.

Rojas’ willingness to take big risks, including possible disciplinary sanctions, to accomplish Petro’s objectives, and his work at the SAE in supporting the agrarian reform, has made him one of Petro’s favourite functionaries. Petro has repeatedly praised and congratulated him, and Rojas is one of the very few officials who enjoys a direct line of communication with Petro, which isn’t the case for most ministers. Rojas was temporarily appointed caretaker director of the National Planning Department (DNP) earlier this year, after Jorge Iván González’s resignation.

Rojas’ promotion to the Ministry of Education was unexpected and met with significant criticism and blowback. Unlike Vergara and most of his recent predecessors, Rojas has no experience in education. Rojas has come under fire for regularly using coarse language and posting insults on social media, against political opponents (often referring to them as hijueputas or viejo(a) hp), the media and the police (calling them tombos hijos de puta). He was also criticized for a more recent tweet in which he said that “you don’t need to be good at math to understand economics.” In an interview, Rojas said that he made those comments in the “context of indignation as a private citizen.”

Petro defended his new minister on social media. After former presidential candidate Sergio Fajardo criticized Rojas’ appointment as a ‘lack of respect’ and called him a bad-mannered person and fanatic, Petro again jumped to his defence, saying that he preferred “the teacher who says bad words to the politician who has committed the worst rudeness to Colombians: condemning them to violence.”

Petro has said that Rojas’ tasks will include the expansion of free public higher education, increasing transfers for education to municipalities and the expansion of history, arts, sports and systems programming classes in schools. Vergara left behind five draft bills, including a second attempt at the education reform as well as a reform to higher education that’s been delayed several times over.

His unstated job may be to incite student mobilization and give impetus to constituyentes universitarias (university assemblies to modify their statutes), one of the locus of popular mobilization that fits with Petro’s ‘constituent power’. Rojas is close to Activistas del Cambio, a group of left-wing activists and agitators with connections to the government and the Pacto, who have helped organize pro-Petro demonstrations, including the protests against the Supreme Court in February. 17 members of Activistas del Cambio have been appointed as the president’s delegates on public universities’ councils. The line between constituyentes universitarias and Petro’s constituent assembly is gray, and the government has tried to build on student mobilization in several public universities (like the crisis at the National University) to mobilize support for its own ‘constituent process’

Housing: Helga Rivas

Petro dismissed housing minister Catalina Velasco and replaced her with Helga Rivas.

Catalina Velasco had been housing minister since the beginning of the administration, back in 2022. While she and her husband are close to Petro, at the same time she was also seen as a Liberal ‘quota’ (her appointment had been recommended by the influential former petrista Liberal senator Julián Bedoya), although not all of the party saw her as one of theirs. Velasco’s job was in Petro’s crosshairs, unhappy with her performance. In January, during an event in Quibdó (Chocó), Petro publicly scolded her for not making sufficient progress in the construction of the city’s water supply network. Petro, members of the Pacto and other critics in cabinet judged her to be ‘insufficiently aligned’ with the government’s agenda, and too close to Camacol, the powerful construction industry lobby. She was also in trouble because of the housing market’s bad numbers: as of May 2024, housing sales were down 14% on the same period in 2023, and housing starts were down 11%.

Helga Rivas is an architect and urban designer who served in Petro’s mayoral administration in Bogotá, first as director of the popular housing fund (2012-2014) and as housing secretary (2014-2015). Under Petro’s presidency, she was an advisor in the housing ministry before managing the adaptation fund, the finance ministry’s agency responsible for risk management, climate change adaptation and disaster recovery. Most recently, she was caretaker director of the UNGRD, the emergency management agency, after Olmedo López was fired.

Rivas may not have been Petro’s first choice. La Silla Vacía reported that he offered the job to María Mercedes Maldonado, Petro’s former housing secretary (2012-2014) in Bogotá and one of Colombia’s top experts on urban and spatial planning.

Transport: María Constanza García

Petro replaced transport minister William Camargo with María Constanza García, who had been vice minister of infrastructure since 2022.

Camargo had been transport minister since April 2023. Camargo, along with Vergara, Mojica and Velasco, was among the ministers that Petro was the most unhappy with. The president considered that the minister didn’t put enough money towards building roads in isolated regions like the Pacific coast and Catatumbo and was unhappy that the bulk of the money and projects remained concentrated in wealthy regions like conservative Antioquia.

María Constanza García is a civil engineer from Cúcuta. She worked in Bogotá’s transport department and TransMilenio before serving as mobility (transport) secretary from 2014 to 2016 during Petro’s mayoral administration. After consulting work in the private sector and the IDB, she was technical projects director in Bogotá’s Urban Development Institute (IDU) during Claudia López’s administration (2020-2022). She had been vice minister of infrastructure in the ministry of transport since August 2022. She is the cousin of Conservative rep. Juan Carlos Wills. The Conservative Party said that comments linking her to the party were ‘fake news’.

Petro’s tweet on her appointment said “onwards with the railways and country roads (caminos vecinales)”, making clear what her priorities should be. Being Petro’s transport minister is a tough job given Petro’s various caprices, like changing the Bogotá metro and his reluctance to fund 4G highways in Antioquia (claiming that they only benefit rich people), or Petro’s big ambitious ideas, like an interoceanic railway connecting the Gulf of Urabá and the Pacific through the Chocó, competing with the Panama Canal. As Petro indicated, one of her main priorities will be to continue working on the reactivation of the railways, trying to turn Petro’s huge ambitions into more modest but attainable objectives.

The final balance

Petro replaced six cabinet ministers, out of 19, in this shuffle. Those who were removed were tired and worn out (Velasco and Osuna), and were perhaps not unhappy to move out, or had fallen into disgrace with Petro (the others) for various reasons.

Of those ministers who were widely considered (by the media) to be threatened, only one survived: mines and energy minister Andrés Camacho, in the job since last summer. Petro was displeased with Camacho’s difficulties in quickly reducing electricity rates in the Caribbean region, which has been Petro’s big focus in the energy sector. Under threat, Camacho worked double time, making policy announcements (including a deal with energy companies that’d reduce rates) and boasting his record. Camacho finished saving his job by announcing a public utilities reform, which would be the government’s big push to reduce utility rates.

It’s not easy to read a common thread in the cabinet shuffle. On the one hand, in appointing Cristo as interior minister, Petro showed that he’s not closed to the centre and that he wants an experienced politician in charge of political negotiations, his administration’s legislative agenda in 2024-25 and the fabled acuerdo nacional. On the other hand, Daniel Rojas’ appointment as education minister sends an opposite message, of Petro falling back on inner circle loyalists who share his strategy of stirring popular agitation and mobilization of the left’s bases under the guise of his ‘constituent process’.

The new ministers in the other four portfolios are similar to their predecessors. At justice, Petro replaced an accomplished liberal-minded lawyer with another. Like their predecessors, the new agriculture, housing and transport ministers are all left-leaning technocrats or ‘experts’. Petro had reproached the outgoing ministers their difficulties and slowness at implementing his policies and agenda. Given that this administration’s trouble at translating its promises and agenda into realities often owe to bigger factors than the ministers in charge, it remains to be seen if the new ministers will have more success. Petro will demand of them that they be more daring, even when that means possibly running afoul of procedures and laws.

In this shuffle, Petro again confirmed that he doesn’t want to negotiate his administration’s ‘governability’ with other parties by offering them ministries (‘quotas’) in exchange for support in Congress, unlike Duque and Santos. There is only one minister who is considered a ‘quota’, sports minister Luz Cristina López, who is the ‘quota’ of the Conservatives’ pro-government faction in the House (led by Ape Cuello).

With this shuffle, Petro has had 38 ministers in 19 ministries in just two years in office, a very high level of ministerial instability compared to his predecessors but that’s not unusual for Petro. Only three ministers are left from the original cabinet in August 2022: Susana Muhamad (environment), Gloria Inés Ramírez (labour) and Iván Velásquez (defence). Petro likes all three of them and clearly retains confidence in them. Susana Muhamad and Gloria Inés Ramírez have been particularly effective in their roles, with Gloria Inés Ramírez having the best ‘legislative record’ of the cabinet, leading the only big social reform that’s been adopted so far (the pension reform). Iván Velásquez’s record isn’t stellar, being a favourite target of opposition criticism for the deterioration of security in several parts of the country and accusations of weak leadership of the armed forces, but Petro has long respected Velásquez and retains confidence in him.

In contrast, six ministries have had three ministers in two years: interior, education, culture, agriculture, transport and sports.

Stay tuned: A post about Colombia’s reaction to the Venezuelan elections will be coming up soon!