The battle for Bogotá

Bogotá has 5.9 million registered voters and elects 18 representatives to the House of Representatives — more than any other constituency…

Bogotá has 5.9 million registered voters and elects 18 representatives to the House of Representatives — more than any other constituency. Around 15.4% of the potential national electorate is in Bogotá.

As the capital and the centre of national media attention, the fight for Congress in Bogotá is always watched closely. Unlike representatives from other departments in the country, Bogotá’s 18 representatives get a fair amount of media coverage and usually focus on national issues, because a lot of them have ambitions to climb up to the Senate.

Politics in Bogotá

Bogotá is very different from the rest of the country in its politics and electoral habits. It has been described for decades as the centre of the voto de opinión (see this post), a symbol of independence and of the maturity and rationality of the urban voter or an island in the context of the national vote. Of course, it’s not that simple: political machines (maquinarias) are definitely weaker in Bogotá than elsewhere but still exist and are behind certain local politicians, while the voto de opinión is not a homogeneous whole in a very diverse and divided city (socio-economically, politically, culturally etc.). Indeed, elections in Bogotá often feature some pretty sharp differences between the wealthy north (particularly the localities of Usaquén and Chapinero) and the poorer south (particularly the poorest localities: Bosa, Usme and Ciudad Bolívar).

Bogotá has stood out from the rest of the country politically for several years: traditional parties are weaker, alternative parties are stronger and the city has leaned to the left of the country for several elections. In 2018, for example, Gustavo Petro (who, of course, had previously been mayor of Bogotá) defeated Iván Duque by 12.4% in the runoff (a difference of over 437,000 votes), while in the first round Bogotá voted for Sergio Fajardo (by 3.9% over Petro, as Duque finished third).

However, Bogotá votes less in congressional elections and more in presidential elections — in 2018, turnout in the congressional election in Bogotá was 48.8% and turnout in the first round was 65%, a 16.2% gap! Over 927,000 more voters turned out to vote for president than for Congress in 2018. Nevertheless, there was a very significant increase in voter turnout between the 2014 and 2018 congressional elections: from just 35.9% in 2014 to nearly 49% in 2018, with an additional 944,500 people voting in 2018. As a result, turnout in Bogotá in 2018 matched the national average (in 2014 it was over 7% below the national average).

That increase in urban turnout in March 2018 was in part due to the concurrent presidential primaries (two of them, on the right and left, won by Duque and Petro respectively). 1.9 million voters in Bogotá voted in the primaries in 2018— 1 million in the right’s primary, 853k in the left’s primary — equivalent to roughly 69% of those who voted in the congressional elections at the same time. Overall, 34% of registered voters in Bogotá voted in one primary in March 2018, one of the highest turnouts for the primaries in the country.

The 2018 congressional elections in Bogotá

The increase in turnout in 2018 was essentially a surge in the voto de opinión which primarily benefited the Greens and Petro’s coalition (Decentes). The Greens won about 40% of their entire national vote in Bogotá alone, thanks to the huge voto de opinión for their top candidate at the time, the popular and respected Antanas Mockus, whose election as mayor way back in 1994 marked one of the first victories of the voto de opinión in Colombia. Mockus won an astounding 327,000 preferential votes in Bogotá, soundly beating Álvaro Uribe, who won about 201,000 votes. For the Greens, Angélica Lozano, who was ‘jumping’ from the House to the Senate (succeeding her partner, Claudia López), also did very well, with over 62,000 votes. The Decentes (Petro’s coalition at the time) passed the 3% threshold thanks entirely to their vote in Bogotá — where they won nearly 45% of their entire national vote.

Overall, in the senatorial contest, the Greens won 22.1% in Bogotá against 18.9% for Uribe’s CD, 9.5% for the Decentes, 8% for CR, 6.3% for the left-wing Polo and 6.1% for the Liberals. The two Christian parties (MIRA and CJL) won around 9% of the vote together, while the Conservatives and Partido de la U were both very weak (4% and 4.5% respectively).

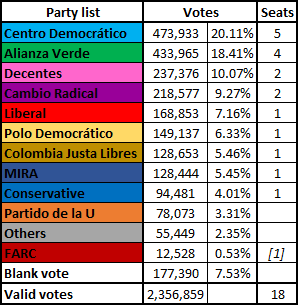

In the vote for the House of Representatives, the top two parties were the CD (20.1%) and the Greens (18.4%), who won 5 and 4 seats respectively. The Decentes won 10.1% and two seats — their only two representatives in the House. CR won 9.3% and two seats, one more than in 2014. The Liberals won 7.2% and one seat, a loss of two seats and the Polo won 6.3% and one seat, a loss of one seat. MIRA and CJL won 5.5% each and one seat each. The Conservatives won 4% and saved their only seat, while the Partido de la U won 3.3% and lost both of its seats.

As in the Senate election, the main winners were the alternative/centre-left movements — the Greens and the Decentes. The Greens, helped by Mockus and Angélica Lozano, won nearly 270,000 more votes than in 2014 and four seats (+1 from 2014). The Decentes’ impressive result (237,300 votes) won them two seats. This new support didn’t even really come at the expense of the existing left-wing Polo, which held its own (a slight dip in vote share but 20,000 more votes) although it lost one seat.

Uribismo also did well, with a higher vote share and raw vote intake (nearly 156k votes more) than in 2014, and it retained its five seats. Cambio Radical (CR) more than doubled its vote from 2014, from 100k votes to over 218.5k votes, but this was actually a somewhat disappointing outcome for their ambitious expectations: with higher turnout, that only translated into two seats, when they were hoping for up to 4 seats. A significant chunk of CR’s extra vote came from the Castellanos family’s evangelical International Charismatic Mission church (MCI), which had been aligned with uribismo in 2014 (and now with the Liberals since 2019): the MCI’s candidate (the fórmula, or upper/lower house ‘tickets’ or alliances, of Claudia Castellanos) won 31,800 votes.

The surge of the voto de opinión hurt parties like the Liberals, Conservatives and the U. The Liberals lost two of their three seats, and their only representative was a candidate who likely appealed to the voto de opinión. The U lost their only seat, and although the Conservatives saved theirs, veteran Conservative incumbent Telésforo Pedraza was defeated.

Finally, the 2018 results showed the strength of the Christian right parties in Bogotá: the MIRA and CJL together won around 11% of the vote and two seats (one each).

The battle for Bogotá in 2022

The battle for Bogotá promises to be fierce in March 2022. Several national and local factors will come into play: the petrista left’s quest for dominance in the capital, the division of the centre/centre-left movements, uribismo’s attempts to save their seats in the face of very strong headwinds and the impact of mayor Claudia López’s unpopularity (around 65%), among other things.

Eleven lists are competing for the 18 seats in the House. Only three of them are closed lists. Unlike for the Senate, the Greens and the Centro Esperanza are not running as a coalition, because only parties which won up to 15% combined in the respective constituency may form coalitions (and the Greens alone won more than that here in 2018). On the other hand, the two weakest parties in the city, the Conservatives and the U, are running a coalition list, as are the Christian parties MIRA and CJL.

The left

On the left, Gustavo Petro’s Pacto Histórico is, like elsewhere, seeking to dominate. At least in Bogotá, they stand a very good chance: in 2018, the Decentes and Polo won 16.4% and although some of those Polo votes from four years ago will go with Jorge Enrique Robledo’s Dignidad party this year, the left should perform even better than in 2018.

The Pacto Histórico is running a closed list, so like with any closed list, the top spots were highly sought after. The first three places are expected to be ‘safe’, while the next 3/4 places will need to hope for a good or very good result. The top candidate is incumbent representative David Racero, who got in in 2018 with only 16,700 votes to his name (far behind the top candidate that year, María José Pizarro, who is running for Senate this year). Racero (a veteran Petro loyalist) has likely gained some name recognition and popularity on the left, particularly with younger voters and online activists, with his time in Congress.

Behind him, there was quite a struggle for second place, and it finally went to María Fernanda ‘Mafe’ Carrascal, a young political influencer and Twitter activist (close to Camilo Romero), who led online campaigns against Luis Carlos Sarmiento’s Grupo Aval. She has attracted attention for a campaign billboard in which she says that she’s not María Fernanda Cabal (far-right CD senator).

Gabriel Becerra, former communist student leader and secretary general of the Patriotic Union (UP), is third on the list. Támara Argote (Polo), fourth on the list, is the daughter of five-term city councillor Álvaro Argote (an old Polo apparatchik, accused of sexual harassment). Her candidacy was controversial and faced accusations of nepotism. Indeed, she got a higher spot than a more experienced figure from the same party: former rep. Alirio Uribe, a human rights lawyer close to senator Iván Cepeda who lost reelection in 2018, is fifth on the list. María José Pizarro’s sister María del Mar Pizarro is sixth on the list. On the whole, the Pacto’s list in Bogotá gave preference to politicians rather than to the ‘new’ social leaderships and diversity it initially promised to promote.

The divided centre and centre-left

The centre and centre-left is dispersed, split between three lists: the Greens, the Centro Esperanza (consisting of Robledo’s Dignidad, Betancourt’s Green Oxygen, the ASI and smaller parties) and the Nuevo Liberalismo (NL). All three lists are open.

As I explained in my first digest here, behind the division of the centre is a fight with eyes set on the 2023 local elections: Carlos Fernando Galán (Juan Manuel Galán’s brother, sixth on the NL’s Senate list) lost the 2019 mayoral election to Claudia López (Green) and will probably run again in 2023, so winning a good result in Bogotá will be crucial for the NL.

On the other hand, the Greens are the largest party on city council since 2019 (with over 570,000 votes), but they are (as always) divided between those who support Claudia López’s administration and those who are more critical of her.

The Greens’ list include two incumbent representatives and one incumbent senator. The top candidate is Katherine Miranda, a young former ‘mockusian’ first elected with around 63,000 votes in 2018, who has defended various causes in Congress (anti-fracking, anti-bullfighting, imprescriptibility of sexual crimes against minors). Now on the left of the party, she has been critical of mayor Claudia López and is running in fórmula with left-wing Green rep. Inti Asprilla who is running for Senate. Very active on social media, Miranda seems to relish going viral and she got a lot of attention for her billboards saying ‘Que no nos abudineen el país’ — a reference to former ICT minister Karen Abudinen, forced to resign in 2021 following a corruption scandal and whose last name gave rise to the colloquial verb abudinear (meaning to steal or defraud). Miranda was ordered to take down her billboards by the CNE, and Abudinen is suing her before the Supreme Court for insult and slander.

The list also includes incumbent rep. Mauricio Toro (#105), first elected in 2018 with the fewest votes of the four victorious Greens (around 19k), who has emerged as a hardworking congressman focused on important issues like small businesses, technology and regulation of the gig economy and digital platforms like ridesharing apps. Unlike Miranda, he’s campaigning on actual policy proposals rather than viral billboards and memes: his billboard, in fact, says “you won’t vote for the best billboard, you’ll vote for the best proposals”.

Other candidates on the Green list include former Liberal rep. (2014–2018) Olga Lucía Velásquez, controversial for having been secretary of government under corrupt Polo mayor Samuel Moreno and who unsuccessfully tried to ‘jump’ to the Senate in 2018 (for these reasons, her candidacy was not welcomed by everyone in the party); former city councillor Jorge Torres (2016–2019), who is supported by Antanas Mockus; political activist Catherine Juvinao, founder of the oversight group Trabajen Vagos on parliamentary absenteeism; senator Jorge Eliécer Guevara, a teacher’s union leader originally from Caquetá; political newcomer Diana Rodríguez Uribe, seeking to replace retiring one-term rep. Juanita Goebertus (an expert on the peace process, transitional justice and post-conflict issues whose retirement is a real loss for Congress); and Gabriel Cifuentes, another political newcomer who was previously secretary of transparency in Santos’ administration and who has worked on human rights and peace issues (his main cause is opposition to conscription).

It will be interesting to see how the Centro Esperanza without the Greens manage to do. The open list’s first candidate is Anastasia Rubio Betancourt, Íngrid Betancourt’s niece. Rubio is a little-known political newcomer who, aside from her childhood, has spent most of her life in the UK or France. Ingrid Betancourt faced accusations of hypocrisy and nepotism for supporting her niece, contradicting her anti-corruption/anti-nepotism rhetoric. Second on the list is student leader Jennifer Pedraza (Dignidad), who was one of the student movements’ representatives during the 2019 national protests and is now a close ally of presidential pre-candidate Jorge Enrique Robledo. The centrist coalition’s list also includes Fernando Rojas Parra (Green Oxygen), who was an advisor to former city councillor Juan Carlos Flórez who is now his fórmula (Flórez is running for Senate).

More than anywhere else, it is in Bogotá that the Nuevo Liberalismo will be focusing their efforts. Unlike their Senate list, their list for the House in the capital is open, although like their Senate list it includes a lot of candidates from civil society with little to no prior electoral experience. The first candidate is Julia Miranda Londoño, former director of the National Natural Parks System between 2004 and 2020.

The traditional and neo-traditional parties

Cambio Radical (CR) did relatively well in 2018, but is unlikely to do as well this year: it will suffer from the loss of the evangelical votes from the MCI (gone to the Liberals) and the retirements of senators Rodrigo Lara and Germán Varón (the second and third most voted candidates for Senate for CR in Bogotá in 2018). In 2019, CR was already one of the biggest losers: it went from being the first party on council in 2015 with over 371,000 votes to only the fourth largest party with 237,600 votes.

Its two main candidates are incumbent rep. José Daniel López, a close ally of David Luna (CR’s top candidate for Senate) and one of the more liberal/progressive voices in CR (very critical of the Duque administration), and Carolina Arbeláez, a first-term councillor who resigned to run — as councillor she was one of the most vocal opponents of the mayor and her campaign is mostly focused on that. López and Arbeláez hold the first and last numbers on the list. CR’s other prominent candidates show that the party, in Bogotá, is cognizant of the importance of the independent voto de opinión, both on the centre and on the right.

The Liberals did poorly in 2018, but they can hope to do a bit better this year. They will gain around 30–35k votes from the evangelical church MCI — in 2019, Sara Castellanos (now running for Senate) was the Liberal Party’s most popular candidate for the city council, with 35,000 votes. Castellanos’ main fórmula is former two-term city councillor Clara Lucía Sandoval. The party’s only representative for Bogotá, Juan Carlos Losada, is seeking reelection. Losada, who is now on Alejandro Gaviria’s campaign team, is on the left of the party and defends causes like peace, animal rights and recreational use of cannabis (he also comes from a political family: his aunt is a veteran six-time city councillor). The fact that the Liberal Party’s two most important candidates in Bogotá are so ideologically different shows says a lot about the contemporary Liberal Party’s ideological coherence…

The Conservatives and the Partido de la U, both of them quite weak in the city, are running a single coalition list (open): together, the two parties won about 172,000 votes in 2018. It is led by Conservative incumbent Juan Carlos Wills, a close ally of Conservative senator Efraín Cepeda (his fórmula) who was first elected in 2018.

Uribismo: In decline?

Bogotá is not an uribista city, but there’s a sizable uribista vote in the capital (particularly in the wealthier north): the CD was the largest party in Bogotá in the 2014 and 2018 elections for the House, winning five seats both time. Like everywhere, however, the CD is bracing for losses this year, although it is unclear exactly how much they will lose. In 2019, uribismo did poorly in Bogotá: not only did their mayoral candidate (in coalition with the Liberals and the rest of the right) Miguel Uribe Turbay do very poorly, but the CD lost one seat in the city council and won just 261,400 votes in total.

The CD has an open list and the first candidate is two-term city councillor Andrés Forero, who resigned from the city council to run. In 2019, he was the party’s most popular candidate, with 32,000 votes. He’s another candidate who still behaves as if he was a councillor, because his campaign has largely been focused on attacking Claudia López.

There are two first-term incumbents on the list: José Jaime Uscátegui (son of retired general Jaime Humberto Uscátegui, sentenced to 40 years in jail for the Mapiripán massacre of 1997, but released in 2017 after taking his case to the JEP, which has nevertheless refused to revise his conviction), who recently filmed himself toilet papering the Constitutional Court after it decriminalized abortion, and iconoclastic Gabriel Santos (son of former vice president and ambassador to the US Francisco ‘Pacho’ Santos).

Santos, the son of former vice president (2002–2010) and ambassador to the US (2018–2020) Francisco ‘Pacho’ Santos, is interesting: distant from the party’s establishment (but tolerated by the boss, Uribe), he has gone against his party’s conservative doctrine on issues like LGBT rights, drug legalization, euthanasia and abortion and he has often criticized members of his own caucus (most recently rep. Edward Rodríguez) and Iván Duque (giving him a grade of just 1.6/5). He wants to embody a “different right” — more modern (opposed to clientelist politics) and liberal, including on civil liberties and moral issues. But in doing so, he’s made very few friends within the party — some party members have even asked for him to be expelled for his liberal views, while others say he’s an hypocrite for being so anti-Duque when his father served in Colombia’s most prestigious diplomatic position under Duque.

The CD’s three other incumbents, including Edward Rodríguez (who won, by far, the most votes of any one candidate in the party in 2018: 104k), are trying to ‘jump’ to the Senate. None of them are leaving behind strong candidates to hold their votes.

The others

The Christian right has a sizable base in Bogotá, as they showed in 2018 and 2019, and running on a single open list, MIRA and CJL came hope to hold two seats again. MIRA rep. Irma Luz Herrera, the vice president of the party first elected to Congress 2018, is running for a second term, again in fórmula with senator Carlos Eduardo Guevara. CJL’s strongest candidates are Sara Caicedo (fórmula of incumbent CJL rep. Carlos Eduardo Acosta, who is running for Senate) and David Gerardo Cote, the son of an evangelical pastor.

The two other lists which complete the electoral panorama are the conservative National Salvation Movement (MSN), which is running a closed list unlikely to win a seat, and the Comunes (ex-FARC) party, which is entitled to five seats in the House, one of which will be held by its top candidate in Bogotá, incumbent rep. ‘Sergio Marín’, a former member of the guerrilla and peace negotiator in Havana.

Wrapping up

Bogotá by itself is not Colombia, but casting about 15% of all votes in the country, it is the most important regional battleground in any election and, unlike in other places, even the election for the House of Representatives has national implications given the high profile of Bogotá’s 18 representatives (and, oftentimes, their future national political ambitions…).

I’m not courageous and gutsy enough to attempt a real prediction. The petrista left, united behind a single closed list, is hoping to dominate in Bogotá: given the city’s political leanings and past electoral history, they will likely do so. In 2018, the left won three seats, split between two lists, and with a good result they can hope for 5 or more seats this year.

In Bogotá, the centre (centre-left) is divided, just like it is nationally (where the centrist coalition recently effectively imploded). The outcome of the battle on the centre/centre-left — how the new Nuevo Liberalismo does, how the Greens fare — will have both national and local implications, with all eyes set on the 2023 mayoral election. For the new Nuevo Liberalismo, a (very) strong result in Bogotá, which was the base of the old Nuevo Liberalismo in the 1980s, is absolutely critical to their consolidation as a relevant political movement nationally. A good result for them would also likely propel Carlos Fernando Galán’s repeat mayoral candidacy next year. The Greens could suffer from the Claudia López’s unpopularity, and in any case the elections will perhaps sort out the tug of war between the different factions and groups within the party.

The growing strength of ‘alternative’ parties and the voto de opinión in Bogotá has hurt the traditional and neo-traditional parties. None of them are likely to do exceptionally well, although there could be some changes on the margins: given dynamics, I would expect CR to lose some ground and the Liberals to do marginally better than four years ago.

Like in many other parts of Colombia, it is expected that uribismo will lose votes and seats — the question is how much. Their candidates, taken as a whole, are weaker than in 2018 and probably bring fewer votes in total.

In any case, Bogotá will be one of the key battlegrounds on March 13.