Petro's consulta popular defeated, labour reform revived

On May 14, the Senate narrowly rejected Petro's consulta popular on the labour reform but revived the labour reform. Petro has angrily denounced the vote as fraudulent.

In the afternoon of May 14, the Senate, by 49 votes to 47, rejected Gustavo Petro’s consulta popular on the labour reform. Minutes before, however, the Senate accepted an appeal of the seventh commission’s decision to kill the reform (back in March), thereby reviving the labour reform and sending it back to third debate, but with less than 40 days to be adopted. Petro and the government have angrily denounced that the vote was fraudulent. The Senate plenary ended in mass chaos and pandemonium, with everyone yelling and shoving, including interior minister Armando Benedetti.

Chaotic day

For more context about the labour reform and Petro’s consulta popular about labour rights, read this post:

Petro presented the 12 questions of his consulta to the Senate, which had 30 days to approve or reject it. The numbers in the Senate were always tight: estimates by the media counted around 47 or so in favour, 47 or so against and the rest undecided or unknown. Benedetti and the government appeared optimistic in the final days, confident that they had the votes.

The Senate debate on the consulta was held on May 13, with the vote the next day.

In the meantime, a potential escape valve for opponents of the consulta appeared. Right after the seventh commission voted to kill the labour reform on March 18, one of the members of the commission, Green senator Fabían Díaz appealed the decision to the plenary, just as congressional rules allow when a bill is rejected. If an appeal is accepted by the plenary, the bill is revived where it left off (third debate, in this case) and sent to another commission for debate.

The government placed little faith in the appeal. Efraín Cepeda, the Conservative president of the Senate (hostile to the government), treated the appeal with disdain, including himself in the special commission formed to study the issue and then ignoring the matter for well over a month. Only on May 12 did Cepeda and three other members of his special commission filed a report asking to deny the appeal. Nevertheless, for a lot of senators opposed to the consulta but worried about the political blowback they’d face for ‘voting against workers’ rights’, accepting the appeal and reviving the reform suddenly appeared as an attractive means of avoiding the consulta while still appearing to support a labour reform in principle. Accepting the appeal, for some of them, would mean implicitly admitting that their colleagues in the seventh commission made a mistake in March. The way in which the 8 senators of the seventh commission swiftly killed and buried the labour reform, without allowing any debate in commission on it, turned out to be a great gift to the government, brandishing it as proof of an institutional blockade (bloqueo institucional) against Petro.

The government was unhappy by this latest development. Antonio Sanguino, the labour minister, said that the appeal was a ‘trap’ to sabotage the consulta. If revived, the labour reform would only have until June 20, the end of the current legislative term, to be adopted (with two more debates and conciliation still to go) or else it’d die for good. Benedetti and Sanguino both said that there would be no time, Sanguino seeing in it a “perverse intention” for the labour reform to receive a ‘second burial’. Supporters of the appeal, like Green senator Angélica Lozano, who gave an impassioned speech on May 13, said that with the appeal there could be a labour reform in law within 38 days (on condition of working hard, seven days a week)—much quicker and cheaper.

The government and its caucus woke up on May 14 to find that Cepeda had scheduled the vote on the appeal before the vote on the consulta, much to their displeasure. The Pacto and its allies furiously accused Cepeda of resorting to deception and dirty tricks by postponing the vote of the consulta. For hours, the Pacto tried everything to modify the schedule, delay the vote on the appeal or even withdraw the appeal, but was denied at every turn by a majority of senators. For their opponents, the Pacto’s obstinate and desperate attempts to postpone the vote on the appeal revealed that their real interest was in the ‘political’ consulta rather than in workers’ rights. The Pacto criticized the hypocrisy of those who suddenly wanted to revive the labour reform, nine weeks after expeditiously killing it.

After hours of tumultuous debate, the Senate finally began debating and voting on the appeal of the labour reform. Benedetti indicated that the government would support the appeal, while seeking a commitment that the reform be adopted before June 20. Suddenly shifting to a more conciliatory mood, Pacto senators said they’d support the appeal all while still insisting on the need for the consulta.

After rejecting, with 68 votes, the motion to deny the appeal, the Senate voted 68-3 to accept the appeal, thereby reviving the labour reform. Immediately afterwards, Cepeda opened the vote on the consulta.

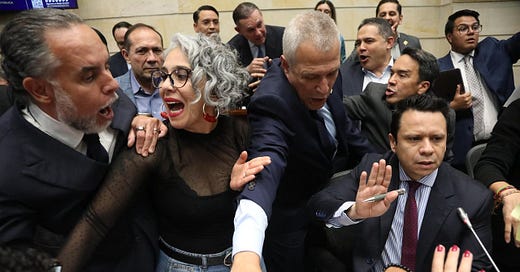

The Senate voted 49 to 47 against the consulta popular. The Senate descended into mass chaos and pandemonium, between opponents loudly celebrating their win (CD senator Paloma Valencia called it a true miracle) and the government and its caucus angrily denouncing ‘fraud’ and foul play, with everyone yelling, pushing and shoving. Interior minister Benedetti lost his temper and furiously argued with the secretary-general of the Senate (the clerk), with some claiming that he came close to hitting him and was held back by several senators. The yelling and screaming kept the secretary-general from formally announcing the final result, despite Cepeda’s repeated insistence for him to do so.

Quickly, Benedetti, Petro and the government cried foul, alleging fraud and dishonesty. Petro, who was in China, soon tweeted that the consulta had not been defeated, but defeated by fraud, comparing it to the 1970 election (the election allegedly ‘stolen’ by Misael Pastrana from Rojas Pinilla, and the foundational moment of the M-19). Benedetti accused Cepeda and the secretary of the Senate of committing criminal offences and ethical breaches. Benedetti has called them both scoundrels.

The government’s arguments for ‘fraud’ are based primarily on two incidents. Firstly, Cepeda abruptly closed the vote as soon as the ‘no’ was ahead: votes can go on for 30 minutes, Cepeda closed the vote less than 3 minutes in, with one Pacto senator (Martha Peralta) unable to come back in time to vote. While questionable, what he did was perfectly legal: it’s one of the presiding officer’s prerogatives to decide when to close votes.

Secondly, there was confusion over a manual (non-electronic) vote by CR senator Edgar Díaz, initially (erroneously) announced as ‘yes’ when his intention was to vote ‘no’, with the secretary-general finally counting his vote (correctly) as ‘no’. Benedetti and Petro have both falsely claimed that a yes vote was ‘striked out’ (after the vote closed) and added as a no, but the piece of paper in question where the secretary wrote down manual votes doesn’t have any strikethroughs. Díaz has insisted that he always intended to vote no. There’d be no reason for Díaz to vote ‘yes’ as his party’s caucus decision was to vote ‘no’.

The chart below details the vote by party.

The Pacto and its allies (Comunes, MAIS) provided 25 votes for the ‘yes’, including ex-Pacto dissident Paulino Riascos, who took his party out of the coalition last year. As noted above, only Martha Peralta was missing. She’s faced many questions, including from angry petristas, as to why she wasn’t there. Her initial justification was that she’d left the chamber after having previously declared a legal impediment to participate, but this doesn’t hold water as her impediment had been resolved an hour before. The next day, Néstor Morales, the host of the morning program on Blu Radio, claimed that the real reason was that she was at the hair salon. She dismissed that claim as misogynistic, and offered ‘colon problems’ as her new excuse. W Radio reported that she didn’t vote because the government hadn’t made a patronage appointment she was waiting on. Peralta has filed a tutela in court to defend her right to vote.

The opposition parties (CD, CR) and the Conservatives carried the no, with all 13 CD senators as well as 12 Conservatives and 8 CR senators voting ‘no’. Among those uribista senators voting ‘no’ was Ciro Ramírez, who returned to his seat just a few days before after being released from prison by the Supreme Court while awaiting trial (Petro angrily tweeted that “they needed to release a convict from prison to vote”). Those who were absent—Conservative senators Carlos Andrés Trujillo, Miguel Ángel Barreto and Diela Liliana Benavides and CR senators Temístocles Ortega, Ana María Castañeda and Didier Lobo—are those who have been most supportive of the government, helping out at key moments (like the pension reform). As their parties had adopted caucus decisions to oppose the consulta, they were required to vote no or run the risk of facing disciplinary sanctions by their parties if they disobeyed—in fact, CR has opened disciplinary proceedings against its three senators for not voting.

Benedetti and Petro have insisted that they had the votes but that Cepeda didn’t let them vote in time. In the case of these six absent senators, that’s unlikely: the most they could do (as they did) to help out the government was to leave the room, but they realistically wouldn’t have voted yes.

The Greens largely voted in favour, with the exception of right-wing YouTuber ‘Jota Pe’ Hernández who voted against and Angélica Lozano, who didn’t vote. She enthusiastically supported the appeal but had made clear from before that she opposed holding the consulta before the 2026 elections. The three senators from En Marcha, the recently revived party of former interior Juan Fernando Cristo, voted ‘yes’. ASI senator Berenice Bedoya, who was part of the eight who killed the labour reform in commission back in March, voted against.

The Liberals and La U were, from the beginning, the key swing blocs in the vote. In the end, a tight majority of both caucuses—7 (out of 13) Liberals, 6 (out of 10) La U—voted ‘yes’, which ultimately wasn’t quite enough for the government. Liberal boss and former president César Gaviria had called to oppose the consulta and threatened his senators with disendorsement in 2026 if they didn’t obey, but seven of them (the most petrista friendly members) voted in favour regardless. Liberal senator Alejandro Carlos Chacón (who is an anti-gavirista rebel within the party) reportedly changed his mind in the final hours, ultimately voting ‘no’.

La U’s Antonio José Correa, who was already actively campaigning in favour of the ‘yes’ to the consulta, carried five of his party colleagues (from the Caribbean) along to vote ‘yes’. But the government was counting on the support of two more senators from the party: Norma Hurtado and Juan Carlos Garcés, close allies of Valle del Cauca governor Dilian Francisca Toro, one of the powerful bosses in the party. In texts from Benedetti during the debate on May 14, published in Cambio, the interior minister accused Dilian of ‘betraying them’ and telling his contact, the finance minister, to ‘stop everything’ for her. According to Cambio’s sources, there was a deal: the government would keep Julián Molina, a ‘quota’ of the Partido de la U, as ICT minister in exchange for the party’s votes in the consulta (sources from Dilian’s inner circle deny such a deal but recognize that the two senators initially intended to vote ‘yes’, but the appeal’s approval made it unnecessary). In reaction to the article, Petro picked a fight with Dilian, saying that her ‘attitude’ undoubtedly was a ‘turning point’ and lamented that ‘class instinct’ overcame the general interest. She tweeted back, saying that he isn’t the only one who fights for workers’ rights, reminding him that La U had presented an alternative text to the labour reform (rather than voting to kill it).

Perhaps crucial in the final vote was the Christian evangelical ‘testimonial party’ MIRA. While MIRA senator Ana Paola Agudelo was among those who voted to scuttle the labour reform back in March, the party hadn’t made clear how it intended to vote on the consulta and the government was apparently banking on their votes (based on the party’s support for direct democracy mechanisms). In the end, their three senators voted ‘no’ (as did the lone senator from Christian evangelical Colombia Justa Libres).

Indigenous senator Richard Fuelantala, whose vote had been key in the pension reform, activated his voting machine but then ended up leaving the room and not voting, as captured on security camera.

What next?

Petro quickly denounced ‘fraud’ and petristas have claimed that the consulta was ‘stolen’, with uribismo and Cepeda as the main culprits.

In photos of chats between Petro and Benedetti published by the media shortly after the vote, the interior minister is seen asking the president “who calls the general strike? Who is told to do it?”

Petro didn’t call for a strike himself, but in his first reaction he called on labour unions and other social movements to meet and decide on the next steps. He hoped for massive turnout on the streets, with the ‘popular coordination’ giving the next steps for ‘the democratic movement’.

Petro directed the people to meet in cabildos (councils) in every municipality to the necessary decisions, and said that he would personally meet the cabildo in Barranquilla on May 19 (later delayed by a day) and “listen to the popular decision as head of the Colombian military forces and legitimate president of the Republic and I will abide by the decision of the cabildos populares of the entire country.” In another tweet, he said that the ‘disgrace’ of the Senate leadership and the ‘obvious fraud and mockery of the constitution made by those who run the Senate’ will be met by a ‘resounding response’

Cabildos and cabildos abiertos have an important place in Latin American history, particularly the wars of independence. In Colombian law, cabildos abiertos are a form of citizen participation, but only at the local level to consider matters of interest to the local community (without taking binding decisions), held at the initiative of 0.5% of the local population—quite obviously, cabildos abiertos can’t be held at a whim simultaneously around the country in reaction to something the Senate has done or to debate labour law. In Petro’s warped view of direct democracy, he instead sees cabildos as a public meetings (organized around labour unions, social movements and other popular organizations), speaking in the name of ‘the people’ (i.e. his supporters) and imposing binding ‘orders’ on elected officials (including himself) who must abide by them—although those ‘orders’ seem to be known ahead of time by Petro. Videos shared on social media by Petro and his supporters show relatively small public rallies attended by Petro’s supporters, organized labour and other social movements close to the government.

In a televised address on the evening of May 14, from China, Petro repeated what he’d tweeted, called on the Senate to repeat the vote and again summoned the people to meet in cabildos abiertos to discuss and decide on the next steps. He said that the answer to the Senate’s decision would be calm, peaceful and joyful but overwhelming.

Petro, however, didn’t wait for the ‘decisions’ of the cabildos abiertos to announce his next steps. As he had anticipated just a day after the vote, on May 19 the government presented a new consulta popular to the Senate, with four additional questions about healthcare reform in addition to the original 12 questions. The Senate will have until June 19 to decide (again) on this second consulta popular. It’s unclear why the government thinks the result would be significantly different than that on May 14.

In support of the government’s second consulta, labour unions led by the CUT, the largest union confederation, called for a 48-hours general strike on May 28 and 29 and a 24-hours general strike on June 11.

In the meantime, the revived labour reform is in a race against time to be adopted in two more debates in the Senate (and conciliation) before June 20. On the night of May 14, Cepeda sent the labour reform to the fourth commission, presided by none other than Green senator Angélica Lozano. The numbers in that commission are not particularly favourable to the government—which only has one ‘safe’ vote there, all others being in opposition or independent—but fairly balanced, with 6 senators having voted for the consulta, 6 against and three not voting. Lozano had made a clear case for the appeal in the Senate and presented a very tight calendar to adopt a labour reform in less than 40 days: with adoption in third debate by May 27, in fourth debate by the full Senate by June 17 and the final text in law on June 20. It’s a schedule that’d require senators to work full-time, six days a week (something that really isn’t in their habits). She held public hearings on May 19, listening to representatives from both business associations (ANDI, Fenalco and sectoral gremios) and unions (CUT, CGT and others), among others.

While the government has requested urgent consideration of the revived bill (giving the Senate 30 days to decide, taking priority over all other matters in the schedule) and Benedetti has pledged to follow, day by day, the progress of the labour reform, others, including Petro himself, seem to have little faith in the congressional process. Petro accused Lozano, who didn’t vote, of wanting to take centre stage by seeking to have the reform adopted by law rather than by consulta. The second consulta could also come to further inflame political tensions, dampening whatever conciliatory spirit there may have been. Cynics would contend that the government has little incentive in getting the labour reform approved, as it’d allow their opponents to score some points and deprive the government of its best justifications for ‘mass mobilization’ against an identifiable enemy.

As I had previously written, the original death of the labour reform and Petro’s first consulta popular was the final breaking point in the relation between Petro and Congress. The Senate’s narrow rejection of the consulta popular has fed into Petro’s increasingly belligerent and radical rhetoric against his opponents, now accused of criminal behaviour by ‘stealing’ the consulta from the people. Regardless of what happens with the revived labour reform, the government wants to maintain the pre-electoral ‘popular mobilization’ it had created in March and wants to stay in campaign mode, against Congress and all other enemies of petrismo.