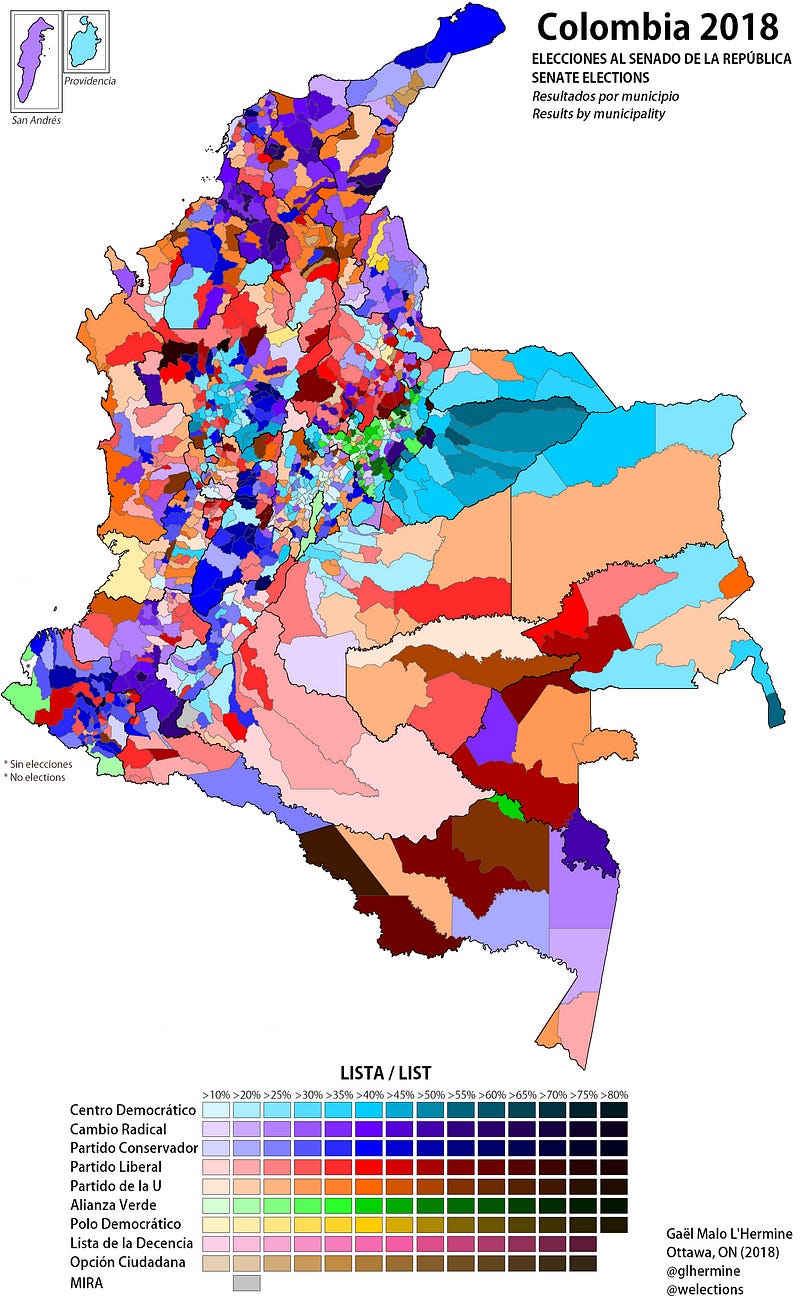

Colombia’s 2022 Senate election

A look at all lists competing in the March 2022 Senate elections in Colombia

Overshadowed by the presidential primaries, the Colombian congressional elections on March 13 are nevertheless very important

I briefly touched upon the electoral system details in my previous post. I will focus on the Senate for now because it’s the most high profile and important.

Colombia’s Congress is very unpopular and has a really bad reputation. The common perception of congressmen is that they are lazy (sleeping on the job or not showing up), corrupt (it’s been referred to as a ‘nest of rats’ more than once), bought off and/or self-serving. Yet, it’s a key institution and any president needs a majority in Congress to pass his/her political agenda. While the legislative is often seen as subordinated to the executive, this hides a complicated and dynamic relationship between the two. All past governments, even Duque who was elected with a promise that he wouldn’t do that, kind of need to engage in transactional deal-making with congressmen to win their support: in exchange for supporting the government’s agenda, congressmen can obtain all sorts of bureaucratic appointments (quotas) in public institutions or government contracts/public works in their regions (known as ‘marmalade’ since the Santos presidency).

Congressional elections are often seen as being dominated by the maquinarias, or the political machines, referring to the clientelistic networks of certain politicians and their clans (it is also known as the voto amarrado, or tied-down vote). Indeed, the machine vote is stronger in congressional elections because the machines (i.e. their leaders) play their own future in those elections, and mobilizing their clientele (through whichever means, which may include vote buying) is key. Whereas in presidential elections, they have fewer incentives to mobilize their clientele as efficiently.

This difference is perceptible in the significant regional differences in turnout between congressional and presidential elections. In the past, it was said that 70% of votes in congressional elections were ‘machine votes’ whereas 70% of votes in presidential elections were ‘opinion votes’, although I really think that’s an overly simplistic way of looking at things. Academics have recently been debating a lot about what maquinarias even mean and they warn against exaggerating differences between machines and opinion: basically, any successful candidate for president or even the Senate will need a mix of the two, and parties clearly try to get the best of both.

As I said, Colombia’s electoral system is unusual in that parties decide whether they run open or closed lists. When it is an open list, each candidate on the list will campaign for him(her)self first and foremost, although the fact that seats are first distributed by party based on the cifra repartidora means that there is still an incentive for vote pooling and any list will try to have a candidate (often #1 on the list) who will pull a lot of votes. For example, in 2018, Álvaro Uribe got 890,000 preferential votes (which is the current record), Antanas Mockus got 550,000 votes, which really helped pull the Greens and Robledo got 229,000 votes which accounted for a fifth of all votes for the Polo.

The Colombian electoral system is always broken and always needs to be fixed, though it’s basically remained unchanged since the big 2003 political reform, and the ‘ideal’ that is often proposed is mandatory closed lists, which politicians like to present a silver bullet to magically strengthen parties and get rid of the personalism. But Colombian parties are weak and they have basically no internal democracy, so a closed list might not be as great as it sounds…

Candidates are identified on the ballot only by a number, which refers to their placement on the list (open lists are ordered too when registered). Candidates will therefore campaign with their party logo and number to indicate to their supporters how to vote. Even on open lists, certain numbers are highly sought after: 1 obviously (though there’s no guarantee the top candidate on an open list will be elected: this happened in 2018 for the Conservatives’ #1 candidate), the other first 10 spots as well as easily identifiable numbers like 100, 10 and other round numbers.

Since 2011, the law requires that at least 30% of candidates on lists in constituencies with 5 or more seats be ‘of one of the genders’ (i.e. women, usually), but there is no requirement for the rank order/placement of women on the lists or alternation of men/women on lists, and then with open lists of course… The 2011 law did have a positive impact on women’s representation in Congress: it increased from 14.2% in 2010 to 20.9% in 2014, and dipped down to 19.7% in 2018.

Since the changes to the electoral system and ballot design before the 2006 elections, there’s been a high percentage of invalid votes in congressional elections: 9.2% for the House, 6.4% for the Senate in 2018 (these percentages are still lower than what they were in 2014–12.1% and 10.2%; 2010–15.1% and 12% and 2006–13.3% and 11%). These numbers are high because the ballot design is so confusing (you can only vote in one constituency, but all constituencies — national/territorial and the ethnic one(s) were on the same ballot!). Electoral authorities have been aware of this since 2006 but in classic Colombian style, it has taken them 16 years to do something. For the first time this year, each constituency will have its own ballot, so this should reduce the number of invalid votes.

It is extremely unlikely that any one list will win an absolute majority of seats in either house. In 2018, the largest party in the Senate was the CD which got just 16.4% of the vote and 19/100 national seats.

Lists for Senate

There are 16 lists for Senate in the national constituency. 8 are open, 8 are closed. I will explain each of them, focusing on their top candidates and their prospects for this year.

Centro Democrático (CD)

In 2018, led by Álvaro Uribe himself, the CD won the most votes and seats in the Senate (16.4%, 19 seats), a result similar to their result in their inaugural election in 2014 (their closed list won 14.3% and 19 seats). Uribe won 891,900 preferential votes, a record (unlikely to be broken this year) which helped carry a number of candidates with much lower individual votes. Without Uribe on their list for the first time ever, and with the party severely weakened by the government’s unpopularity, Uribe’s greater unpopularity and their more obvious internal divisions, the CD is likely to lose a few seats this year — a loss of around 5 seats would not be surprising, I think (maybe even optimistic for them). Their top candidate, chosen by Uribe, is Miguel Uribe Turbay, who was the right/uribismo’s mayoral candidate in Bogotá in 2019 (finishing a paltry fourth with 13.6% after a pretty bad campaign, as memorialized by this cringe video). Uribe Turbay is the grandson of former Liberal president Julio César Turbay (1978–1982, undoubtedly one of the worst presidents in modern Colombian history) and the son of Diana Turbay (a journalist who died in a botched rescue attempt while she was held hostage by Pablo Escobar), he served as a Liberal city councillor in Bogotá (2011–2015) and was Enrique Peñalosa’s secretary of government (2015–2018); he was chosen because he offers a moderate face, and has the same surname as Uribe (and he has really dropped his maternal surname this time around…). Although he’s learned his uribista lessons well, Miguel Uribe isn’t a great candidate: he’s the epitome of the young rich political heir who owes a lot to his surname, and he seems to be campaigning for Bogotá city council rather than Senate sometimes. Three of the unsuccessful presidential pre-candidates are on the list: former Casanare governor Alirio Barrera (#2, but his candidacy caused a spat with his cousin, incumbent senator Amanda Rocío González, who got 46,000 votes in 2018) and senators Paloma Valencia (#10) and María Fernanda Cabal (#100). Cabal, the standard bearer for the furibista far-right (in a recent leaked recording she called Duque a ‘mamerto [pejorative term for leftist] left-liberal’), wanted to be the top candidate and is now competing with Uribe Turbay to win the most preferential votes. 7 incumbent senators are not seeking re-election (and one is running for another party, which is illegal), including prominent figures like Ernesto Macías (former president of the Senate and close Duque ally), party ideologue José Obdulio Gaviria and close Uribe ally María del Rosario Guerra. Some, like Guerra, are leaving ‘heirs’, while for others the hope is that newcomers will fill the holes (most notably would be Bogotá rep. Edward Rodríguez, a Duque loyalist, who is ‘jumping’ to the Senate and got 104k votes in the capital in 2018). The list has its fair share of controversial candidates, like Daniel García, a former Uribe administration official who became Odebrecht’s Colombian lobbyist after being removed from office for lying about his qualifications (and, later, the link between Zuluaga and Odebrecht in 2014).

Cambio Radical (CR)

With the expansion of the Char clan across the Caribbean and Vargas Lleras’ todo vale alliances with all kinds of machines around the country, CR was the biggest winner in 2018, gaining 7 seats in the Senate, going from 9 to 16, making it the second-largest caucus. Circumstances are much different this year. The top candidate is former ICT minister (2015–2018) David Luna, a former Liberal who became close to Vargas Lleras while in cabinet. Luna previously served one term in the House (2006–2010) and was the Liberal mayoral candidate in Bogotá in 2011, winning 4.2%; in 2020 he helped create an association of app-based services like Uber and Rappi. Luna is a clear attempt to compete for ‘opinion votes’ in a party which has a reputation of ethically questionable machine politics (and also to send the message that Vargas Lleras still has power here). CR is losing a few key senators — Vargas Lleras ally Germán Varón (whose endorsement of Alejandro Gaviria caused the Betancourt psychodrama), Rodrigo Lara (who had the third most votes in CR in 2018), Claudia Castellanos (from the evangelical MCI) and the corrupt-criminal Aguilar clan. With a few exceptions, CR’s list is replete with machine politicians and incumbents — including Alex Char’s dumb brother Arturo (who won the most votes of any CR candidate in 2018, over 126k), who faces an open investigation in the Supreme Court for electoral crimes (vote buying) and allegedly being behind Aída Merlano’s escape in 2019. The Char clan should lose some ground, but still remain quite strong. CR is losing a few key senators — Vargas Lleras ally Germán Varón (whose endorsement of Alejandro Gaviria caused the Betancourt psychodrama), Rodrigo Lara (who had the third most votes in CR in 2018), Claudia Castellanos (from the evangelical church MCI) and the corrupt-criminal Aguilar clan. To compensate for that, CR is largely relying on representatives ‘jumping’ to the Senate and machine candidates. Notably, CD senator Amanda Rocío González is running for reelection for CR, after a feud with her cousin.

Conservative Party

The Conservatives lost four seats in 2018, going from 18 to 14 seats (actually 13 because Aída Merlano’s seat was ruled vacant, silla vacía), and won about 1.9 million votes. The goal is to maintain those numbers this year, although the party’s most voted senator from 2018, David Barguil (146k votes), is not on the ballot. The party’s top candidate is seven-term senator Efraín Cepeda, who won the second most votes for the godos in 2018 (124.4k). Cepeda, whose base is in Atlántico, is one of the most prominent Conservative senators (he was president of the Senate in 2017) and although he doesn’t have any major corruption scandal or controversy to his name, he’s the quintessential Colombian congressman — that is, an opportunist who supports whichever government and knows how to play his cards to ensure the placement of his people as ‘quotas’ in various public entities. Cepeda at the top of the list shows that the Conservatives aren’t even trying to even give an appearance of ‘renewal’. Most of their candidates are either incumbents (including controversial ones like Laureano Acuña, the Barreto clan of Tolima, Nadya Blel, the Merheg clan of Risaralda), ‘heirs’ of retiring incumbents or new groups now allied with the Conservatives (most notably the much weakened Aguilar clan).

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party lost two seats in 2018, falling to 14 seats, although its vote share remained stable and its total vote increased to 1.9 million. It will be an uphill challenge for the divided party to retain those numbers, but the party — which has no presidential candidate yet — is betting on maintaining a strong presence in the Senate to negotiate its support for the presidential election. Like the Conservatives, the Liberals are not even trying to even give the appearance of fresh blood: their top candidate is three-term senator Lidio García Turbay, who was the party’s most voted candidate in 2018 with 121,700 votes and served as president of the Senate in 2019 (also a vallenatero). García Turbay comes from an influential (and controversial) political family in Bolívar, his stronghold (his cousin Dumek was governor 2016–2019), and has an old investigation for parapolítica that was reactivated in 2021. 6 of the party’s 14 incumbents are not seeking re-election (Horacio José Serpa, Luis Fernando Velasco, Andrés Cristo, Rodrigo Villalba etc.), and party boss César Gaviria’s strategy to compensate these losses is with the remaining incumbents, representatives ‘jumping’ to the Senate (like Alejandro Carlos Chacón from Norte de Santander) and even more political machines, particularly from the Caribbean coast. There’s no shortage of controversial candidates on the list, like Aída Merlano’s ex-husband, former four-term Conservative Barranquilla city councillor Carlos Rojano. The evangelical church MCI, which was with CR in 2018 (and with uribismo in 2014), is with the Liberals since 2019, and former Bogotá city councillor Sara Castellanos (daughter of CR senator/MCI co-owner Claudia Castellanos) is 12th on the list.

Partido de la U

The Partido de la U (which now stands for Partido de la Unión por la Gente) has been in decline for years and was the biggest loser in 2018, losing 7 seats and falling from 2.2 million votes to 1.8 million votes. The party, now led by the powerful ‘baron’ of the Valle, former governor Dilian Francisca Toro, is facing further loses this year: it lost two of its most famous senators to the Pacto — Roy Barreras (who was the U’s top candidate and most voted candidate in 2018 with over 110k votes) and Armando Benedetti, expelled in 2020 (Roosvelt Rodríguez, a former ally of Toro, also announced his support for Petro recently and left the party, he won 107,000 votes in 2018); and only 6 of its 11 remaining senators are running for re-election. The U’s top candidate is Olympic medallist Catherine Ibargüen, a political newcomer to give the party a fresh face (Afro-Colombian woman, athlete etc.). But she is only nice facade: behind her, the Partido de la U is betting on Toro’s own structure, incumbents, representatives jumping upwards, heirs and new/recycled machines (some with closets overflowing with skeletons) to retain its seats. The list includes, for example, the brothers of the infamous ‘Ñoños’ of 2014 Bernardo ‘el Ñoño’ Elías and Musa Besaile (the former incarcerated since 2018 and recently sentenced to 8 years in jail for taking bribes from Odebrecht; the latter incarcerated since 2017 for bribing judges in the ‘cartel of the toga’ to freeze his investigations for parapolítica), Julio Elías Vidal and incumbent senator Johnny Besaile.

Alianza Verde-Centro Esperanza

The Green Alliance and the Centro Esperanza coalition (minus Nuevo Liberalismo) are running a coalition list for Senate. Like everything in the centrist coalition, the Senate list was a long, tortuous process with drama, infighting, disagreements and about-faces. In 2018, the Greens, thanks to Antanas Mockus’ candidacy, which won a massive 549,000 preferential votes, were one of the main winners, gaining 4 seats for a total of 9 and winning 8.6% of the vote. In addition, Jorge Enrique Robledo, with the Polo at the time, won 229,000 preferential votes. The Green-Centre coalition list is an open list with candidates from the Greens, Dignidad, ASI, Verde Oxígeno and Colombia Renaciente. The list’s top candidate is former chief peace negotiator and 2018 Liberal presidential candidate Humberto de la Calle, a veteran politician who has held various political offices since the 1990s but has never served in Congress. De la Calle is a respected and unifying figure for the disparate patch-up that is the centrist coalition, who all pushed him to be their top candidate. He would have preferred a closed list, and even at one point said he wouldn’t run if it wasn’t a closed list, but he relented as they insisted. They hope that de la Calle will attract a lot of ‘opinion votes’ to boost the list, as Mockus did in 2018 (not sure if 550k votes for him is on the cards though). The list includes 6 of the 9 Green incumbents (notably Angélica Lozano, the wife of Bogotá mayor Claudia López, and one of the best senators), other politicians (some former congressmen and others like former Caldas governor Guido Echeverri, a traditional politician turned more ‘alternative’), a few ‘heirs’ (like Miguel Samper, the son of former president Ernesto Samper), trade union figures and some candidates from civil society. Because the Greens are divided between Petro and the centre, some of their candidates on the list support Petro/the left (notably Antioquia rep. León Fredy Muñoz, detained at the airport in 2018 with cocaine in his luggage, and Bogotá rep. Inti Asprilla). Speaking subjectively, there are some very good candidates on the list but also a few who I’m much cooler about.

Pacto Histórico (PH)

Gustavo Petro wants to presidentialize the congressional elections, with the stated goal to win a congressional majority on March 13, and Petro’s campaign is telling its supporters ‘how to vote for Petro’ on March 13: for him in the primary, and for the Pacto’s closed lists for the Senate and the House. In 2018, Petro and his allies’ Decentes coalition won 3.4% and elected 3 senators (one of whom, ‘Manguito’, turned out to be a right-winger…), in addition to the four Polo senators which are now part of the PH coalition. The Pacto’s gamble this year is to win the most votes and seats, with a closed list where voters only vote ‘for the logo’ — the expectations range from 10 to 20 seats (the record for a closed list is the CD in 2014, which got 19 seats). Putting together a closed list was difficult, given that the placement on the list (in the top 10–20 spots) is of the utmost importance and there were a lot of politicians and groups who wanted to secure their spots while the Pacto also promised to guarantee the representation of social movements and ethnic minorities. Not everyone was pleased with the outcome: most notably, presidential candidate Francia Márquez threatened (without much bite) to leave the Pacto after the coalition didn’t keep its promise to her movement Soy Porque Somos (none of them in the first 20, when Petro had promised a spot between 11 and 15 to one of them). The list’s top candidate is senator Gustavo Bolívar, an author and telenovela screenwriter (considered the father of the ‘narcogenre’) and very visible Petro loyalist (in fact, he’s been Petro’s videographer in the Senate). Bolívar is a divisive figure who is disliked by several of his colleagues in the PH; he’s kind of a blowhard and very theatrical (I feel he’s kind of petrismo’s answer to the loudmouth uribistas) and he has his own share of past demons and current controversies. He got the top spot ahead of his rival, Bogotá rep. María José Pizarro (daughter of assassinated M-19 commander Carlos Pizarro), who is second. The top spots alternate between men and women (lista cremallera in Spanish). The top 20 positions on the list gave priority to incumbents, politicians and the various political groups within the Pacto — rather than the ‘diversity’ and social movements that it had promised to include. Candidates include senators Alexander López (Polo, 3), Iván Cepeda (Polo, 7), Wilson Arias (Polo, 15), Roy Barreras (ADA, 5), Aída Avella (UP, 4), former senator Piedad Córdoba (8, again at the centre of major controversy regarding the actual extent of her ties with the FARC and overreaching her role as mediator with Chávez in ‘humanitarian exchange’ talks for the release of FARC hostages in 2007), former presidential candidate Clara López (12) and Boyacá rep. César Pachón (MAIS, 17). The list also includes the ‘quotas’ of senator Armando Benedetti, presidential candidate Camilo Romero (his sister-in-law) and Medellín mayor Daniel Quintero.

Nuevo Liberalismo

For its first election, Juan Manuel Galán’s Nuevo Liberalismo is running alone, separate from its other coalition partners, with a closed list with alternation of men and women in the first 12 spots (lista cremallera in Spanish). Galán insisted on a closed list to promote the new New Liberalism as a liberal alternative, ensure gender parity and highlight new leaders. The top candidate, Mabel Lara, shows the message that the list wants to send. Mabel Lara, an Afro-Colombian woman from Cauca, is a journalist and award-winning news presenter (most recently with Caracol Radio) who has also worked in social development projects in her native region. She has never run for office before and is a new face who can attract a lot of ‘opinion votes’. The list includes a fair number of candidates from civil society with little or no prior electoral experience, which is pretty rare in Colombian congressional elections (even for ‘alternative’ parties and the left) — academics like Sandra Borda (#3), Afro human rights leader and conflict victim Yolanda Perea (#5), feminist human rights lawyer Viviana Vargas (#7). To be sure, there are politicians, both old and new figures of the revived movement, most notably Juan Manuel’s younger brother Carlos Fernando Galán (#6, former CR senator and runner-up in the 2019 mayoral election in Bogotá).

MIRA-Colombia Justa Libres (CJL)

The Christian parties MIRA and Colombia Justa Libres (CJL) are running in coalition this year. In 2018, MIRA won 3.2% and 3 seats and CJL narrowly passed the 3% threshold in the final count (in the pre-count it was below 3% but the final count somehow ‘found’ 33,500 more votes for them), and three seats each. They are running an open list — MIRA usually had closed lists in the past, but ran with an open list in 2018, while CJL had a closed list in 2018. The top candidate is incumbent MIRA senator Ana Paola Agudelo, who was representative for Colombians abroad (living in Spain) between 2014 and 2018 and was elected to the Senate in 2018, as MIRA’s top candidate (with 71,200 votes). Including Agudelo, there are three incumbent senators on the list (only one of them from CJL) and one representative (Bogotá CJL rep. Carlos Eduardo Acosta).

Fuerza Ciudadana

Fuerza Ciudadana is the movement of Carlos Caicedo, the left-wing governor of Magdalena since 2020 and Petro’s sole (token) rival in his 2018 primary (Caicedo won a respectable 15.3% and over 500k votes). Part of the Pacto, it is however running its own open list which includes a lot of petristas — in part it is a reaction to the battles within the Pacto for the limited but highly disputed spots on its closed list, in part a bit for Caicedo’s movement to gain party status for his own presidential ambitions in 2026. Caicedo is a left-wing politician who was mayor of Santa Marta (2012–2015), and has been for decades the sworn enemy of the old corrupt traditional clans which have dominated politics in Magdalena, and in 2019 he defeated them in the gubernatorial election. But Caicedo has adopted some of the dubious practices of traditional politicians (using the municipality and public resources to favour his movement electorally) and while he has undoubtedly been the target of political persecution/lawfare by his powerful enemies, he’s also faced a lot of accusations and open judicial investigations — corruption allegations for irregularities in unfinished infrastructure projects and even an unresolved homicide case from 2000 (with conflicting stories). The list is led by Gilberto Tobón, an academic and political commentator (with over 400,000 Twitter followers) who is famous for hot takes that go viral on social media. Caicedo’s ally and former mayor of Santa Marta (2016–2019) Rafael Martínez is third on the list; Martínez is also involved in the open corruption charges against Caicedo. The list also includes Hollman Morris, a Petro ally who was Colombia Humana’s mayoral candidate in Bogotá in 2019 — at the time he was accused of domestic violence and sexual violence, but refused to step aside, which divided the petrista left and damaged Petro’s feminist creed after (although Petro defended him in 2019, he seems to have distanced himself and didn’t want him to run for Congress). There are also a few left-wing influencers on the list.

Comunes (ex-FARC)

Comunes, as the FARC party renamed itself last year, is again entitled to five seats in the Senate as per the 2016 peace agreement. In 2018, the FARC party won just 0.3% — around 50,000 votes — and no better in the 2019 local elections. In addition to the security challenges faced by reintegrated members of the ex-FARC guerrilla (assassinations etc.) and their obvious toxic reputation which makes them persona non grata in all political alliances (even the left), the party has been badly divided by factionalism and infighting since 2020. A faction led by senators ‘Victoria Sandino’ and Israel Zúñiga ‘Benkos Biohó’, who unsuccessfully asked to split the party last year, have complained that control of the party has been monopolized by a small ‘authoritarian’ clique around the party’s leader Rodrigo Londoño (‘Timochenko’, the last commander of the FARC) which has purged dissidents. The Comunes’ closed list shows little renewal of party ranks and little interest in cleaning up the party’s very negative image — four of the five top candidates are former members of the guerrilla; three of the five top candidates are incumbent senators (Sandino and Zúñiga were excluded). The top candidate is senator Julián Gallo (alias Carlos Antonio Lozada), member of the party leadership and former member of the FARC Secretariat. In January 2021, the JEP (transitional justice) charged eight members of the former FARC Secretariat, including Gallo and Pablo Catatumbo (third on the list) with crimes against humanity and war crimes for hostage taking and kidnapping during the armed conflict, the first macro-case opened by the JEP. All those charged acknowledged truth and responsibility. They could still be able to participate in politics with the sanctions imposed by the JEP (assuming they acknowledge truth and responsibility) if the JEP finds the sanction compatible with political participation.

Movimiento de Salvación Nacional (MSN)

The revived right-wing MSN is running a closed list with 16 candidates. The top candidate is José Miguel Santamaría, a businessman and son of a former Conservative governor of Cundinamarca. Santamaría ran for Senate four year ago for the CD and won 16,000 preferential votes, and recently participated in a committee seeking the recall of Bogotá mayor Claudia López.

Estamos Listas

Estamos Listas is one of the more interesting novelties in this election: it is a collective feminist movement, which first appeared in Medellín in 2019, when it won one seat in the city council with 3.8% of the vote (28,000 votes). It is now trying to expand to the national level, after having successfully collected 76,000 valid signatures to appear on the ballot. Obviously, in its internal organization (radical democracy/grassroots direct democracy, collective leadership and decision-making), who it represents and what issues it brings forward, it is a new and unique political movement in a rather machista country like Colombia. In Medellín, it put a feminist agenda on the table and raised awareness about the realities faced by women — notably, it has helped in the search for missing women and girls. They are running a closed list with 11 women (there are 5 men on the list symbolically, in the last spots, to comply with legal requirements, but they are not presented as candidates by the movement). Candidates cannot have held public office before or participated in the last elections, so all candidates are from civil society, and some come from marginalized or underrepresented groups (underrepresented departments, LGBT, Afro-Colombian women). The list is led by Elizabeth Giraldo, an historian and specialist in urban studies who is a political advisor to the movement’s councillor in Medellín. They are following the same strategy they used in Medellín in 2019: a self-funded campaign, which rejects donations from businessmen or business associations/lobbies, with a collective campaign emphasizing the movement and its proposals rather than individual candidates. Estamos Listas recently voted to endorse Francia Márquez’s presidential candidacy, and they’ve received the support of former representative Ángela María Robledo, who was Petro’s running mate in 2018.

Movimiento Unitario Metapolítico

A 1990s throwback, the Metapolitical Unitarian Movement is the political group of one of the craziest figures in Colombian politics, Regina Betancourt, commonly known as Regina 11 (or to her critics as ‘the witch’, or to her followers as ‘Mama Regina’), a mentalist, psychic, mystic and faith-healer who leads a movement/cult known as saurología (or Sabiduría Universal Reginista). Claiming to have prophetic powers thank to a childhood experience in which she made mental contact with Cardinal Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, she became famous thanks to a radio program in the 1970s, ran for president three times (1986, 1991 and 1994), and served as city councillor and senator (1991–1994). The symbol of her movement is a broom, which she promised would sweep away the immorality that plagued the country, and she gave away magnetized ‘bank notes’. She performed rituals and spells inside the Capitol, which somehow isn’t the weirdest or most awful thing that’s taken place there. Her political career ended abruptly in the mid-1990s: she was mysteriously kidnapped and held hostage for five months and was later convicted of extortion (for demanding money from people in her office in Congress), though she was later found innocent. She largely disappeared from politics afterwards but continued as a spiritual leader for her cult and developed her own line of products which she sells, although she claims that politicians have continued to visit her to seek her support (and votes) before reverting to calling her a witch after winning. Her movement has made it back on the ballot with a closed list of 11 candidates, although Regina 11 is not a candidate herself. She is now an anti-vaxxer and conspiranoid, who claims that COVID-19 is part of a plan to create a global dictatorship and reduce the adult population with a bacteria and vaccine. She also says that drinking your own urine can prevent COVID-19 and a bunch of other things. Her platform also proposes a resocialization program for homeless people where they’d be sent to farms with no money and cellphone and would receive treatment from doctors and psychologists. The most votes she ever won in the 1990s was around 64,000 in the 1994 presidential election, while she won a seat in the Senate with around 30,000 votes in 1991.

Gente Nueva

A little-known anti-corruption movement running a closed list with 19 candidates. It supports Rodolfo Hernández, but the support is not reciprocal: Rodolfo put out a statement saying that the only congressional list he supports is his own Liga’s list for the House in Santander.

Movimiento SOS Colombia

SOS Colombia stands for ‘Sector Organizado de la Salud’ and is a group of healthcare workers opposed to Colombia’s healthcare system. They have a closed list with 25 candidates.

Details on the main candidates can be found on La Silla Vacía, while the ballot papers and booklet with all candidates are available here.