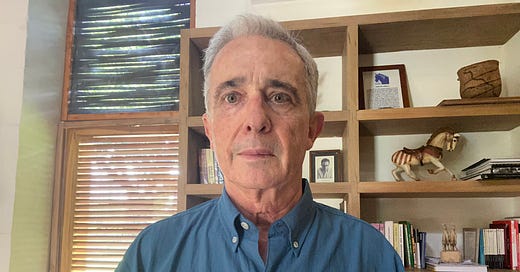

Álvaro Uribe on trial

Former President Álvaro Uribe will stand trial for witness tampering and procedural fraud. A look at the case's history and the political consequences of what will be a very politicized trial.

On April 9, the Attorney General’s office (Fiscalía) announced that former president Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) will stand trial for witness tampering and procedural fraud.

This is the latest twist in a case which began when Álvaro Uribe was placed under house arrest in August 2020 by order of the Supreme Court, and it follows former attorney general Francisco Barbosa’s repeated failed attempts to close the case. The trial of the former president will be very political.

An old case

The roots of this case date back to accusations, over a decade ago, made against Uribe by left-wing senator Iván Cepeda, claiming that Uribe and his brother Santiago had participated in the formation of the paramilitary groups in Antioquia in the 1990s. Uribe in turn accused Cepeda of presenting false testimonies, seeking out statements from ex-paramilitaries in jails to implicate and harm Uribe and manipulating witnesses. This lawsuit came back like a boomerang against Uribe. In February 2018, the Supreme Court—which investigates and judges sitting congressmen—closed the case against Cepeda but instead opened a preliminary investigation against Uribe for allegedly manipulating witnesses. Uribe’s defence had one weak to file an appeal against the decision. The events at stake in this current case occurred during these few days, when his defence was looking for evidence to present their appeal.

According to the Court, Uribe’s lawyer (Diego Cadena) and intermediaries (like then-uribista representative Álvaro Hernán Prada, now CNE magistrate) contacted ex-paras in jail in an attempt to convince the key witness, Juan Guillermo Monsalve, to retract his testimony against Uribe and to blame Cepeda for manipulating him, in exchange for favours and money. Uribe’s defence says that Monsalve was the one who contacted them, in a plot to harm Uribe. Cepeda’s lawyer told the Supreme Court that Monsalve was receiving messages and visits to change his testimony. Based on this new evidence, in July 2018, the Supreme Court announced a formal investigation against Uribe.

Álvaro Uribe initially announced his resignation from the Senate, claiming to be “morally impeded to be a senator,” in reality an attempt to have his case transferred from the Court to the slower Fiscalía. The news sent political shockwaves and rattled his party, the Centro Democrático, just days before his political protégé, Iván Duque, was to take office. However, just a week later, Uribe backtracked and withdrew his resignation, after his lawyers recused the magistrates who had opened the formal investigation.

On August 4, 2020, in a bombshell decision that made international headlines, the Supreme Court’s criminal instruction chamber ordered that Uribe be placed under preventive house arrest, to avoid obstruction of justice. The news rocked the political world and sparked furious reactions from uribistas, including Iván Duque. Uribe and his supporters claimed that he was a victim of political persecution by a biased court.

On August 18, Uribe resigned from the Senate—for good this time—complaining that the arrest warrant against him violated due process and was based on inferences with no direct evidence. Once again, his goal was to have his case transferred to the Fiscalía. In late August, the Supreme Court accepted that Uribe’s case be sent to the Fiscalía, ruling that it was no longer competent to criminally investigate him.

In the meantime, Iván Duque’s university friend, Francisco Barbosa, had become attorney general in February 2020. The Fiscalía, in the hands of Barbosa, offered a slower and friendlier investigation. Uribe’s strategy worked. In October 2020, a judge lifted Uribe’s house arrest order, as requested by the defence and the Fiscalía.

Barbosa’s helping hand

In March 2021, the prosecutor, Gabriel Jaimes, announced that the Fiscalía would ask for the case to be closed (precluded). Jaimes said that there was no evidence that Uribe had committed some of the crimes he was suspected of, or that there was no evidence that Uribe had been the material author or participant in other crimes. Jaimes had collected new evidence which largely helped Uribe, and had refocused the investigation on the victims and key witnesses rather than in determining Uribe’s culpability. Uribe thanked God for this “positive step” while uribistas proclaimed that the “montage” against Uribe “fell apart.” Cepeda complained that Jaimes offered no guarantees for victims and questioned his impartiality.

The Fiscalía’s arguments were the opposite of the Supreme Court’s arguments which, in ordering Uribe’s detention in 2020, judged that there was sufficient evidence against him and tentatively pointed to his culpability. Indeed, Jaimes asked the Supreme Court to investigate Cepeda for the statements by ex-paras claiming that he’d offered them benefits in exchange for incriminating Uribe. Jaimes gave credibility to witnesses who testimonies had been dismissed by the Court, considering them false.

In April 2022, circuit judge Carmen Ortiz denied the Fiscalía’s request to close the case. The judge considered that there were indications that Uribe may have committed the crimes he had been charged with. Moreover, she criticized Jaime’s investigative work, saying that he ignored some evidence or selectively used pieces of evidence to support his argument, that he failed to call upon relevant witnesses and failed to ask more questions during interrogations. Ortiz largely sided with the Supreme Court’s hypotheses.

The judge’s decision severely undermined the Fiscalía’s credibility, reinforcing perceptions that, under Barbosa, it had become dedicated to defending Uribe at all costs. It was also, obviously, a blow to Uribe: he would be forced to defend his innocence for years to come, and he would not be able to accuse a career judge (not involved in any political confrontations with Uribe in the past) of political bias, as he had with the Supreme Court’s magistrates. Political reactions from uribismo largely expressed their sorrow and solidarity with their ‘eternal leader’, rather than attacking the judge in question.

The Fiscalía did not appeal the judge’s ruling, which left it with two options: change their mind and formally indict Uribe, or ask again for the case to be closed using other legal grounds for preclusion (there are seven, he had used two of them). He chose the latter. In August 2022, a new prosecutor, Javier Cárdenas, again asked for the case to be closed. Cárdenas largely repeated the same arguments as his predecessor, having only collected the evidence that the first judge had said was missing. There were gaps in his arguments and he ignored evidence that had been used by the Court. La Silla Vacía showed that he misrepresented and omitted one of the key pieces of evidence, the transcription of a spy watch recording of the meeting in jail between Monsalve and Cadena. The Fiscalía considered that this recording, having been edited, did not support Monsalve’s claims that Cadena had tried to get him to change his testimony in exchange for benefits.

In May 2023, another circuit judge, Laura Barrera, again denied the Fiscalía’s request to close the case, considering that there was sufficient evidence to bring Uribe to trial. Once more, the judge questioned the prosecutor’s mediocre investigative work, saying that he’d deliberately ignored evidence that contradicted his arguments and hadn’t used the new evidence to fill the gaps in Jaimes’ arguments. Like the first judge, she considered that there were indications that Uribe had participated in the crimes he was accused of, and the Fiscalía had failed to conclusively prove his innocene. The Fiscalía appealed the decision, leaving the final word in the hands of the Superior Court of Bogotá.

In October 2023, the Superior Court of Bogotá rejected the Fiscalía’s appeal and preclusion of the case. The decision, taken by three magistrates, was unanimous. The magistrates said that because of gaps in the evidence and inconsistencies in witness testimony, the court could not revoke the first instance decision. The magistrates said a “deeper and more diligent investigation” was lacking, and that the Fiscalía had failed to contrast its hypothesis with the available evidence.

Uribe deplored the ruling, saying that it created “another additional obstacle” preventing him from campaigning in the local elections (held in late October) but later recognizing that the magistrates “did not express political hatred.” Uribista politicians claimed that there was a suspicious coincidence between the court’s decision and the local elections, although in the end it’s unlikely that the decision moved many votes in any direction.

The court’s decision left the fate of the case in the hands of the Fiscalía, which again needed to choose to either request a new preclusion or take Uribe to trial. However, time was running out for Francisco Barbosa in his quest to save Uribe: his term was to end in February 2024. Shortly after the ruling, a new prosecutor was appointed. This prosecutor resigned less than three months later, ostensibly for personal reasons, although coincidentally he resigned on the day that he needed to make a decision on the case. Just three days later, the fourth prosecutor needed to resign because of a conflict of interest. Daniel Coronell had revealed that the prosecutor had written an op-ed column in 2020, opining in favour of Uribe and against the Supreme Court. A fifth prosecutor, Gilberto Iván Villarreal Pava, was appointed in mid-January.

Francisco Barbosa’s term as attorney general ended on February 13, 2024. His repeated attempts to close Uribe’s case, and the three setbacks suffered at the hands of five judges, are a big part of his legacy as attorney general. For practically the entirety of his term, Barbosa did everything he could to protect Uribe and close the case against him. He failed in his attempts, and badly damaged the Fiscalía’s credibility by showing a clear political bias in Uribe’s favour. As the judges said, the Fiscalía’s investigation was shallow and lazy, deliberately ignoring or misrepresenting evidence to fit their argument.

The trial of Álvaro Uribe

Luz Adriana Camargo was elected attorney general on March 12 and took office ten days later.

On April 9, the Fiscalía announced that Álvaro Uribe would stand trial, charged with three counts of bribery in criminal proceedings (soborno en la actuación penal) and two counts of procedural fraud (fraude procesal). The Fiscalía’s indictment stated that Uribe directed Diego Cadena, directly or through intermediaries, to promise money or other services or benefits to selected witnesses in exchange for not telling the truth, or testifying about an alleged plot against Uribe by Cepeda. In doing so, Uribe misled the Supreme Court. The prosecutor contends that Uribe “directed his will or desire to the criminal objective set […] for his own benefit or that of third parties, and to the detriment of the effective and correct administration of justice and the rights or superior interests of their victims, in this way determined the commission of the punishable conducts outlined.”

If found guilty, Uribe faces 6 to 12 years imprisonment on both charges, as well as fines and disqualification from public office for 5 to 8 years.

This is the first time that a former president of Colombia stands trial in a court of law in recent history. Former dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (1953-1957) was convicted in a political trial (juicio político) in Congress, but his conviction was later overturned by the judiciary.

Barbosa may have been unsuccessful in his attempts to close the case, but he helped Uribe by allowing the clock to tick in his favour. The prescriptive period (statute of limitations) is six years, and runs out in October 2025. This leaves the justice system will relatively little time to find Uribe guilty or innocent. The Colombian justice system is slow and this trial will be very political. Following the carrousel of prosecutors since last fall, journalists like Daniel Coronell and lawyers like Miguel Ángel del Río (left-leaning star lawyer for the victims in this case) said that prescription was Barbosa and Uribe’s lawyers’ strategy.

A very political trial

Uribe released a lengthy (8 page) statement about the decision. Uribe said that the “trial is being brought forward due to political presumptions, personal animosities, and political vendettas, without evidence that would allow to infer that I sought to bribe witnesses or deceive justice.” He said that his only desire was “to search for the truth and to the verify the reports of manipulations by politicians to affect my reputation.” Anticipating the heavily politicized nature of his impending trial, Uribe questioned the impartiality of the new attorney general, stating that she is very close to defence minister Iván Velásquez, who has “animosity” towards Uribe and his family. His statement also repeated his old argument that the Supreme Court magistrates are politically biased against him, or have connections to his political opponents.

Since then, Uribe has posted a series of videos providing evidence of a supposed ‘set up’ against him. One of his main arguments is that his phone was ‘illegally’ intercepted (tapped) by the Supreme Court during their investigation against him. Uribe says that his phone was initially intercepted by mistake, as part of a separate investigation against a congressman (Uribe’s phone number was provided instead of the congressman’s number), and that the court allowed the wiretap to continue for 32 days. In January 2024, the Supreme Court ruled that these phone wiretaps were legal because they’d been obtained legally through court order.

The right-wing media, led by Semana, has started arguing that the case against Uribe is a political trial and implies that he may be a victim of political persecution or political revenge. Semana columnist and news director of La FM radio Luis Carlos Vélez wrote that the Fiscalía’s ‘about-turn’ was very preoccupying, claiming that the prosecutors had abruptly changed their mind without explaining why, drawing an obvious connection with the change of attorney general. His column notably fails to make any mention that the Fiscalía’s attempts to close the case were rebuffed on three separate occasions by five judges and magistrates.

Like all right-wingers are bound to do, Semana’s article also drew connections between Uribe’s fate—a popular former president who successfully cornered the FARC and courageously fought against criminals—and that of the ex-FARC’s leadership—sitting in Congress, free, still not convicted to date and having paid no reparations to their victims. Uribe did so himself, tweeting that those responsible for atrocious crimes were given political eligibility while anyone convicted of stealing a bike or a cellphone can’t be elected, and that his “convicted companions” lack any political rights. These are two different things—the ex-FARC’s leadership are subject to transitional justice, not the Fiscalía or the courts, as part of the 2016 peace agreement, and the case against Uribe has no direct connection to the FARC peace process or its consequences—but it’s very easy to make those sorts of comparisons, and makes for a rather convincing political argument for the right.

At the other end, the left rejoices that Uribe will finally stand trial and that nobody is above the law. The left has long hated Uribe for the serious human rights violations that took place during his term (false positives, illegal wiretapping of political opponents, journalists, activists and magistrates by the intelligence services) and the allegations of his connections to paramilitaries and drug traffickers. Some left-wingers even consider him to be a war criminal, mass murderer or drug trafficker, as evidenced by the viral success of the web series Matarife in 2020 (the serie’s creator, Daniel Mendoza, was ordered by the Constitutional Court to rectify his accusations against Uribe). While this case is about judicial procedures more than anything else, it’s nearly inevitable that, because of the strong passions that Uribe’s name still evokes, his trial will become a political trial of the Uribe era, with the judge’s decisions used and twisted to fit right- or left-wing narratives about Uribe.

After Petro’s victory in 2022 the uribista vs. petrista vendetta had died down a bit, as both men (though not necessarily their followers) had buried the hatchet, with Uribe leading a ‘constructive opposition’ that was at times quite tame, much to the chagrin of far-right uribistas. This temporary cessation of hostilities began to end a few months ago when Petro appointed former paramilitary commander Salvatore Mancuso, recently repatriated from the US, as a gestor de paz (a special designation to play a role in the peace process). Mancuso has spoken out, accusing Uribe of complicity in the El Aro massacre in 1997 and more extensive connections to paramilitarism. As Petro’s rhetoric has gotten less conciliatory and more radical, populist and combative, he’s started publicly attacking Uribe again—like in March, when he accused him of being a large landowner and not paying property taxes on his finca. The trial will certainly revive the uribista vs. petrista conflict.

Uribe’s trial will also be the first crucial test of Luz Adriana Camargo’s impartiality and independence, even though the decision to bring him to trial was taken by Gilberto Iván Villarreal, the last prosecutor appointed to the case by Barbosa. She will be under pressure to prove that she isn’t there as a weapon of revenge for the left, and the right will be demanding that she takes big decisions in the case against Petro’s son.

Nevertheless, the Uribe era is also increasingly distant in public memory. Uribe’s popularity suffered massively from Duque’s unpopularity, with the former president falling into negative territory for the first time. Some polls show that his popularity has recovered quite substantially since 2022, likely thanks to Petro’s unpopularity. In general, a lot of people have tired of politics being defined around Uribe and he no longer enjoys the widespread affection and support he had for years. Besides, political conflict has moved on from Uribe, and now centres around Petro.

Ever since he resigned from the Senate in 2020 and with his attention focused on his legal problems, Uribe has gradually become less visible in daily politics. In stark contrast to all previous elections since 2002, Uribe played a much smaller role in the 2022 elections, in which uribismo did not have a presidential candidate from within their own ranks. While his status as a former president and his enduring popularity on the right means that he remains a sort of moral leader for the right and senior statesman, Uribe is not really the most prominent face of the right-wing opposition to Petro. All this means that while Uribe’s trial will certainly arouse passions on all sides and be a very political trial, it won’t dominate political debate in the way such a trial would have ten years ago.