Breaking point: The death of the labour reform and Petro's consulta popular

The death of the labour reform in the Senate and Petro's call for a referendum on labour rights is the breaking point in Petro's relations with Congress & the start of the 2026 campaign.

On March 18, the seventh commission of the Senate voted to kill Petro’s labour reform. In reaction, Petro announced that he’d call for a consulta popular (a type of referendum) to let the people decide on the labour reform. The death of the labour reform and the consulta popular is the final breaking point in the relation between Petro and Congress. Petro has given up on passing his social reforms through Congress, and is betting everything on ramping up ‘popular mobilization’ in a pre-electoral year, coupled with increasingly belligerent and radical rhetoric against his political opponents. The consulta popular, which needs to be approved by the Senate before it’s held, is part of that strategy, which holds both risks and rewards for Petro. All in all, it’s the real start of the 2026 campaign.

The labour reform

Petro’s labour reform was first presented in March 2023, but ran out of time and died in the House, failing to pass in first debate in June 2023. The government presented it again in August 2023. After being paralyzed for six months since December 2023, it finally passed, in extremis, in first debate in the seventh commission of the House in June 2024. It was adopted in second debate by the plenary of the House in October 2024, with 93 votes in favour. To secure its passage in the House, then-labour minister Gloría Inés Ramírez made significant concessions to other parties, notably on collective (organized labour) rights.

The reform moved on to third debate in the seventh commission of the Senate, an hostile environment where, just a year earlier, the healthcare reform, another of Petro’s big social reforms, was killed by nine of the commission’s 14 members.

The government said that the reform would improve workers’ rights to guarantee “decent and dignified work” and job security, reducing labour precarity. It’d have reversed some key changes made by Álvaro Uribe’s 2002 labour reform, which had reduced labour costs for employers and made it easier for them to hire (and fire) contract workers or irregular shift workers, with the unfulfilled promise of creating 160,000 jobs a year.

Critics said the reform would increase labour costs on employers, increase the rigidity of the labour market, reduce competitiveness and put up to 450,000 jobs at risk while doing nothing to create new jobs or reduce labour informality (around 57% of the employed population). They also argued that the government’s vision of labour relations is archaic, ignoring the new realities of the labour market and working styles. The reform was strongly opposed by business groups, including the powerful employers’ association ANDI and merchants’ federation FENALCO, who aggressively lobbied against in Congress. Opponents expressed concerns about the impact of the reform given consistently high unemployment (10%), a relatively cool economy (1.8% growth in 2024, projected 2.6% growth in 2025), low productivity, high non-wage labour costs and an increase in business closures in 2024.

Among other things, the labour reform included:

Stricter limits on fixed-term contracts (no longer renewable indefinitely, limited in length to four years), seeking to make indefinite term contracts the general rule. However, unlike in the government’s draft, they wouldn’t have been limited solely to an employer’s ‘temporary need’ or specific task. The reform also included new regulations on the use of contractors and subcontractors, and limits on the use of temp agencies.

Redefining night shift working hours as 7pm to 6am (since 2017 it is from 9pm to 6am, and was from 10pm to 6am from 2002 to 2017). Night shifts receive additional pay (recargo nocturo) of 35% of the salary.

Maximum hours of work set to 8 hours per day and 42 hours a week. A 2021 law had reduced the maximum duration of the workweek from 48 hours to 42 hours, but had removed the 8 hours/day limit.

Increase in extra pay for work on Sundays and holidays from 75% to 100% of the salary, as it was prior to 2002. This would be gradually implemented until 2027.

Apprenticeship contracts defined as fixed-term employment contracts and apprentices would be paid 60% of the minimum wage during the in-class portion and 100% of the minimum wage during the productive portion (currently, the salary is agreed with the employer), with full benefits coverage. This was one of the main causes of the Pacto Histórico and the government.

‘Reinforced labour stability’ against dismissals for people with disabilities, pre-retirees and pregnant women and mothers of newborns up to 6 months. They could only be dismissed for just cause, with additional approval from a labour inspector required for pregnant women and mothers.

Specific procedures to impose disciplinary sanctions or dismissals with just cause. An article increasing compensation for termination without cause was eliminated in second debate, another concession by then-minister Ramírez.

Regulation of work on digital delivery platforms (like Colombian company Rappi). App workers would be either dependent (employees) or independent, with social security coverage. Platforms would be required to register with the labour ministry and inform their workers of any employee monitoring software.

Implementing ILO convention 189, requiring written employment contracts for domestic workers. The reform also provided for the formalization, through special employment contracts, of professional athletes, artists and transportation workers.

Flexible workdays or workstyles for employees with caretaker responsibilities (children, elders, family members with disabilities)

Requiring employers to grant leave to employees to attend medical appointments (including for menstrual pains), their children’s school obligations or address matters arising from gender-based violence.

Increase in paternity leave from 2 weeks to 4 weeks by 2026. The government’s draft originally increased it to 12 weeks, before being lowered to 6 weeks in first debate and 4 weeks in second debate. An additional article also created three days paid leave for newlyweds. In second debate, the Conservatives were able to eliminate an article that’d have extended parental leave to same-sex couples.

As a measure to reduce labour informality, allowing part-time social security contributions by micro-enterprises who formalize their existence.

Stronger legal protections against workplace discrimination and harassment. Guarantee of all labour rights to immigrants, and facilitate the regularization of irregular migrants who have signed a labour contract.

Requiring employers to implement reasonable adjustments to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities and facilitate the inclusion of vulnerable groups; they must also comply with protection orders for victims of gender-based violence, and and preferably relocate the workers affected. Companies with 100 or more employees would be required to hire at least two persons with disabilities per 100 employees.

Ban on union service contracts (contratos sindicales), a type of civil law contract between employers and trade unions for certain activities. A form of labour outsourcing/subcontracting, the workers involved don’t benefit from standard labour rights, so they’ve been increasingly misused to circumvent labour law (over 2,600 new union service contracts were signed in 2021-23, mostly in healthcare).

Protecting workers possibly affected by automation and decarbonization (through reconversion, training or relocation).

Updated definition of remote working/telework, with the creation of a connectivity allowance to teleworkers who earn less than two minimum wages, instead of the transportation allowance.

In first debate, despite the government’s opposition, a block of 17 articles related to collective (organized labour) rights, intended strengthen collective bargaining and trade unions, was eliminated. The eliminated articles included measures to strengthen collective bargaining, extending it to levels beyond the company (to branches, sectors and business groups) and forcing unions to agree on a single list of demands to avoid a multiplicity of collective agreements; broadening the right to strike (replacing the total ban on strikes in public services with requirements for minimum services in essential public services during strikes, reducing the majority required in strike votes, no limits in time etc.). The only things left from this block of articles included guarantees for the right to organize and a list of punishable anti-union conducts.

In second debate, the plenary of the House eliminated articles that’d have created a special contract for agricultural workers, the category of agricultural day labourers (jornal agropecuario), guaranteed a salary equal to the minimum wage, and housing guarantees for rural workers on their place of work (at charge of the employer).

After passing in the House in 2024, the reform needed to be adopted in the Senate, in third and fourth debates, by June 2025. In the seventh commission of the Senate, the government has no majorities—with only five reliable votes out of fourteen members. In April 2024, by a 9-5 vote, it had buried Petro’s healthcare reform. A quasi-identical scenario played out again in March.

On March 11, eight of the commission’s members (2 Conservatives, 2 Centro Democrático, 1 Liberal, 1 ASI, 1 MIRA and 1 Colombia Justa Libres) co-signed a ponencia negativa (proposal to kill a bill) against the labour reform. Their arguments against were those repeated by opponents of the reform for months. They claimed that their decision was technical, not political, reached following public hearings and technical discussions.

Petro’s reaction: Popular mobilization and consulta popular

Petro’s reaction was immediate and fiery. He tweeted that if the commission voted against the reforms, there would be a rupture between Congress and the government. A bit over an hour later, he accused the commission of betraying the working people of Colombia.

In a first televised address that evening, Petro said that there had been an ‘institutional blockade’ (bloqueo institucional) against the ‘popular vote of 2022’, a claim that he’s made several times over the past months in the face of congressional opposition to his political agenda. In sentimental terms, he claimed that the labour reform only sought to pay workers a bit more for overtime work, give time off to menstruating women, provide labour stability rather than ‘slavery’ to workers via indefinite contracts and pay apprentices ‘a fair salary, not exploitation’. He accused the senators of “defending the rich man and not Jesus the carpenter.” Petro said that his call for a great national agreement (acuerdo nacional), which he’d repeatedly mentioned since 2022 but never fleshed out, had failed and had been mocked.

Claiming that an institutional blockade is a “dictatorship against the popular vote,” Petro announced that he’d call for a consulta popular (a type of referendum) to let the people decide on the labour and healthcare reforms.

Petro, surrounded by ministers, politicians, indigenous leaders and other activists, all silently holding placards in favour of the social reforms, gave another televised address that night. Invoking the 2021 national protests, he defended his social reforms, claimed that he was willing to sit down in good faith to discuss them, but that they’d only been met with mockery and deception by the oligarchy seeking to prevent reforms and maintain an unjust and violent social order. He vowed that the government wouldn’t back down from its reforms, but that it was now up for the people to decide given that Congress blocks them. In populist style, he called on the working people to mobilize and take to the streets in defence of the government’s reforms, and in his usual grandiloquent terms, said that the people would decide if “they want to be slaves or if they want to be free and dignified.”

A consulta popular (popular consultation) is a mechanism of citizen participation under the Constitution and respective laws. According to article 104 of the Constitution, the President, with the prior approval of the Senate, may “consult the people on matters of national importance.” A consulta popular may be held at any level at the initiative of the president, governor, mayor or by popular initiative (requiring signatures of 5% of registered voters nationally). A consulta popular is a simple, general question(s) on an issue of general importance, it cannot amend, repeal or create legislation (a question cannot include a legal text), but rather imposes a binding mandate for action by Congress (or local bodies).

Adoption requires not only a majority of ‘yes’ votes on the question(s) but also participation of at least a third of registered voters, or roughly 13.6 million people today. Making matters more difficult, it can’t coincide with a regularly scheduled election. Over 40 consultas populares have been held at the local level, but there’s only been one national consulta popular—the 2018 ‘anti-corruption’ consulta popular.

Breaking point

The death of the labour reform is the final breaking point in the relation between Petro and Congress. It’s the end of the road for his social reforms, which have been the main focus of the administration since early 2023. The labour reform is dead, the second attempt at the healthcare reform will almost certainly face an identical fate as it faces third debate in the very same (in)famous seventh commission of the Senate. The one social reform that was adopted by Congress, the pension reform, is in limbo because of the possibility that it’ll be struck down by the Constitutional Court in the coming weeks (on procedural grounds, because of the way it was hurriedly adopted last June).

Petro’s increasing exasperation with Congress, which he sees as an institutional blockade (or a golpe blando, soft coup) against his ‘popular mandate’, has been growing since last year and it’s now reached a breaking point.

He’s given up on pushing his reforms through Congress and is betting everything on ‘popular mobilization’, in a pre-electoral year. His rhetoric has gotten more radical, populist and belligerent. Gone are any conciliatory gestures. Petro now says that the acuerdo nacional, which parts of the administration were still seriously talking up as recently as last summer, has failed. This strategy holds both potential risks and rewards for the government.

The consulta popular—if it’s held—is a very risky gamble for the government. The turnout quorum encourages opponents to promote abstention, just adding to structural abstention that’s high in Colombia (the high-turnout 2022 runoff had 42% abstention). In Álvaro Uribe’s 2003 referendum against ‘politicking and corruption’, held at the peak of his popularity, only one question passed the 25% turnout threshold. The 2018 consulta fell just short of the threshold (32.1%), and it was on an uncontroversial topic with broad agreement across the political spectrum and mass media. To pass, Petro’s consulta popular would need over 13 million voters turning out (and a majority voting in favour). In the 2022 runoff, Petro won 11.3 million votes (and 8.5 million in the first round). That’ll be extremely hard to reach, particularly when opponents can quietly promote abstention.

‘Being counted’ in a national vote is a big risk for an unpopular government that has approval ratings oscillating around 35%, and Petro exposes himself to the prospect of an electoral humiliation just a year before the 2026 elections. Some government supporters, like Pacto senator (and 2026 candidate) María José Pizarro, recognize that it’ll be an immense challenge.

On the flip side, the consulta popular allows the government to set the narrative for several months and move the conversation away from the recent scandals, crises and government failures and dysfunction that have dominated headlines for months. Petro can force the media and the opposition to talk about, and take a stance on, workers’ rights, where at least some of his ideas are likely popular with many voters.

The other objective of the consulta popular/popular mobilization is to put the country firmly into pre-electoral campaign mode (as interior minister Armando Benedetti effectively admitted) galvanizing the left-wing base (shifting their focus away from disappointment with the government’s paltry record) and organizing the Pacto’s campaign for 2026, ahead of possible internal primaries to choose a presidential candidate and set the congressional list in October. The mobilization for the consulta will unite the Pacto, dissipating internal divisions, and give visibility, resources and a platform for Pacto congressional and presidential hopefuls (who’ll need to organize and mobilize left-wing voters to vote in the consulta, if it is held). The left’s leading presidential contenders—Pizarro, Gustavo Bolívar (who finally resigned as DPS director on April 30) and Daniel Quintero—have all enthusiastically endorsed the consulta and began campaigning for it.

Popular mobilization

Even while it took its time to define the questions for the consulta popular, the government began campaigning for it through calls for popular mobilization.

It joined the unions’ call for nationwide demonstrations on March 18, the day that the seventh commission was to vote on the labour reform. Petro and the government published promotional videos calling on people to join the demonstrations on March 18 in support of the social reforms.

Petro also decreed March 18 to be a ‘civic day’ (día cívico) to ‘guarantee’ the people’s right to publicly express themselves in favour of the social reforms. A ‘civic day’ isn’t a public holiday and only gives a day off to government departments in the executive branch. Petro had already impetuously decreed a día cívico two days before a major opposition protest in April 2024 (as well as for the day after the Copa América final last year). Very few local governments followed suit—the mayors of Bogotá, Medellín and Cali all opposed it, with Bogotá mayor Carlos Fernando Galán insisting that schools would be open and warning of consequences for teachers who didn’t work that day to join the protests.

As expected, on March 18, the seventh commission of the Senate voted 8-6 to kill the labour reform. Norma Hurtado (La U), who had voted with the majority to kill the healthcare reform last year, didn’t join their ranks this time and instead had presented an alternative proposal.

Meanwhile, just outside, in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolívar (and in cities across the country), supporters of the government demonstrated in favour of the reform and the consulta popular. There were around 20,000-30,000 people in Bogotá, a significant but not massive number. Petro’s speech, filled with muddled historical comparisons and references to Bolívar, García Márquez and 100 Years of Solitude, focused on attacking Congress, dehumanizing them (“because they are not human beings”) and accusing them (branded as the oligarchy/political class) of betraying the people, of being sell-outs to greed and money, of being rich nepo babies who sneer at poor working mothers. Against these ‘sell-outs’, Petro (invoking Bolívar) said that the people must rebel against tyranny.

Consulta popular

As has been mentioned above, a consulta popular is one of the mechanisms of citizen participation in Colombian legislation.

According to the law, the president submits the questions to the Senate, which has 30 days to decide. The Senate cannot modify the questions, it simply votes for or against the organization of the consulta popular (an absolute majority, 53 votes, is required). If the Senate gives the green light, the president will set the date for the consulta popular, which must be held within three months following the Senate’s approval.

The government took a long time to come up with the questions for its consulta popular. Interior minister Armando Benedetti opened an online platform allowing the public to submit their own questions, but it’s not clear how many people submitted questions or if the government took these suggestions into account. Yet, even before it had even come up with the questions, the government started promoting (campaigning for) the consulta popular. In Cali, a Pacto representative set up the first committee for the ‘yes’ in early April. The national confederation of juntas de acción comunal (JAC) announced their support for the consulta at an event at the palace in early April. Legally, there’s a very fine line between just promoting a means of civic participation and actively campaigning for the ‘yes’ in a consulta popular that hasn’t been approved. The law makes clear that campaigns may only start from the date that the consulta popular has been approved and called—and anyone campaigning for or against, including the government, must notify electoral authorities (the CNE).

On April 22, more than a month after Petro announced the consulta, Benedetti and labour minister Antonio Sanguino finally announced the 12 questions that’d be submitted to the Senate by Petro on May 1, labour day. Following some modifications to the text of the questions, the twelve questions are:

Do you agree that daytime work should last a maximum of 8 hours and be between 6:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m.? (¿Está de acuerdo con que el trabajo de día dure máximo 8 horas y sea entre las 6:00 a.m. y las 6:00 p.m.?)

Do you agree that work on Sundays or holidays should be paid with a 100% surcharge [of the regular salary]? (¿Está de acuerdo con que se pague con un recargo del 100% el trabajo en día de descanso dominical o festivo?)

Do you agree that micro, small, and medium-sized productive enterprises, preferably associative one, should receive interest rates on credit and incentives for their productive projects? (¿Está de acuerdo con que las micro, pequeña y medianas empresas productivas, preferentemente asociativas, reciban tasas de interés en materia de crédito e incentivos para sus proyectos productivos?)

Do you agree that people should be able to have the necessary leave to attend medical appointments and leave for incapacitating menstrual periods? (¿Está de acuerdo con que las personas puedan tener los permisos necesarios para atender citas médicas y licencias por períodos menstruales incapacitantes?)

Do you agree that companies should hire at least two people with disabilities for every 100 employees? (¿Está de acuerdo en que las empresas deban contratar laboralmente al menos 2 personas con discapacidad por cada 100 trabajadores?)

Do you agree that apprentices of the SENA and similar institutions should have an employment-type apprenticeship contract? (¿Está de acuerdo con que los aprendices del SENA y de instituciones similares tengan un contrato de aprendizaje de carácter laboral?)

Do you agree that workers on delivery and transportation platforms should agree on their type of contract and be guaranteed social security contributions? (¿Está de acuerdo que las personas trabajadoras en plataformas de reparto y transporte acuerden su tipo de contrato y se les garantice el pago de seguridad social?)

Do you agree with establishing a special labour regime so that agricultural employers can guarantee labour rights and fair wages for agricultural workers?(¿Está de acuerdo con establecer un régimen laboral especial para que los empresarios del campo garanticen los derechos laborales y el salario justo a los trabajadores agrarios?)

Do you agree with eliminating outsourcing and labour intermediation through union service contracts? (¿Está de acuerdo con eliminar la tercerización e intermediación laboral mediante contratos sindicales?)

Do you agree that domestic workers, community mothers, journalists, athletes, artists, drivers, among other informal workers, should be formalized or have access to social security? (¿Está de acuerdo que las trabajadoras domésticas, madres comunitarias, periodistas, deportistas, artistas, conductores, entre otros trabajadores informales, sean formalizados o tengan acceso a la seguridad social?)

Do you agree with promoting job security through indefinite-term contracts as a general rule? (¿Está de acuerdo en promover la estabilidad laboral mediante contratos a término indefinido como regla general?)

Do you agree with establishing a special fund for the recognition of a pension bonus for farmers? (¿Está de acuerdo con constituir un fondo especial destinado al reconocimiento de un bono pensional para los campesinos y campesinas?)

Unsurprisingly, all twelve questions are written in a way that no one can reasonably answer ‘no’ to any of them, although all questions raise valid points of debate as to how they could be implemented through legislation and the extra costs they’d imply for employers.

All questions pick up some of the key elements of the failed labour reform, particularly the issues most important to the left and the labour movement—overtime hours and pay, apprenticeship contracts, job security/labour stability, formalization, contracts for agricultural workers and so forth. The first question, redefining regular daytime working hours from 6am-6pm, as it was until Uribe’s 2002 reform (instead of 6am-9pm), has become a regular part of Petro’s speeches—who presents it as a scientific truth in an equatorial country where the day ends around 6pm year-round. It’s also a question that basically everyone would say ‘yes’ to (the same goes for the second question, which also reverses another part of the 2002 reform).

Petro formally presented the text of the consulta to the Senate on May 1. The Senate has until June 1 to decide. If it approves it, the government must call it for within 90 days, the latest possible date for the consulta being September 1.

In the hands of the Senate

As Benedetti has admitted, the government doesn’t have a majority (53 votes) in the Senate necessary to green light the consulta, but he says he’s optimistic. In reality, the numbers are very close. The government starts off from a base of 25 votes (Pacto and allies), plus around six pro-government Greens (like León Fredy Muñoz, Ariel Ávila and Inti Asprilla).

At the other end, the opposition Centro Democrático (CD) and Cambio Radical (CR), who have 23 votes together, will both vote against the consulta. The Christian evangelical parties (MIRA and Colombia Justa Libres—4 seats), whose two members on the seventh commission both voted to kill the reform and have since been regularly attacked by Petro (e.g. “those who uphold Jesus and vote against the working people betray Jesus’ putative father”), are unlikely to support the consulta.

The government needs votes from the Liberals, La U and to a lesser extent, the Conservatives, whose caucuses are split between anti-government members and others more sympathetic to the government. In La U, Antonio Correa is already actively campaigning for the ‘yes’ in the consulta and the government hopes that he can bring around five more of the party’s ten senators on board (in addition, Julián Molina, the new ICT minister, is a ‘quota’ of the party and has connections to its caucus). The Liberals have at least seven senators who may side with the government on the consulta. The Conservatives, spearheaded by the president of the Senate Efraín Cepeda and the president of the seventh commission Nadia Blel (she accused Petro of threatening and intimidating her after the Pacto supported a protest in front of her house), are likely to oppose the consulta but the government has some affinity with three senators. According to a count by La Silla Vacía, there’d be 47 votes for the consulta, 47 votes against and eleven undecideds.

In the middle of all this, three bills related to labour and employment rights have been presented in the Senate since Petro first announced the consulta. Some of these can be used by opponents to sell the consulta as unnecessary, or as an easy exit for senators to justify voting against the consulta without being branded as enemies of the working people. The most significant of them is the Liberal Party’s ‘mini reform’, presented by senator Alejandro Carlos Chacón (a ‘swing vote’ in the party), which consists of only two points: night shift hours (7pm-6am) and 100% extra pay for work on Sundays and holidays. The government dislikes it (Sanguino, the labour minister, has called it a ‘bonsai’ of the original reform), in good part because the lead rapporteur (ponente) for it in the seventh commission is Liberal senator Miguel Ángel Pinto, part of the eight who voted down the original reform. In an underhanded attempt to sabotage it, the government, on Petro’s orders, has sped up the legislative process for it (using a mensaje de urgencia, the respective house has 30 days to decide on it). Through this expedited process, the seventh commissions of both houses will discuss it jointly, but vote separately, where the government’s majority in the lower house’s commission would suffice to kill it. Petro and Benedetti have said that the the mensaje de urgencia is to force the Liberals to decide where they stand, although in a radio interview Benedetti left open the possibility of the government supporting the ‘mini reform’ on the condition that they can add things to it.

Campaign mode

Petro will place enormous pressure on Congress to approve the consulta popular. Since March, he has repeatedly said that the Senate will need to show if it obeys ‘the people’, like in a democracy, or if it betrays them.

Since 2023, Petro has looked to the streets for the backing that he doesn’t have in Congress. Time and again, he’s called for mass popular mobilizations to support his administration’s social reforms or to show his strength. In numerical terms, the opposition’s protests have often drawn bigger crowds, like in April 2024, and the demonstrations staged by the government have sometimes had quite meagre turnout (and claims that attendees were forced or paid to be there). However, Petro has, at times, managed to draw large crowds, proving that he still has substantial (and passionate) support from his left-wing base.

To formally present his consulta popular for the Senate’s consideration, Petro, who loves grandiose (pompous) theatrics, chose an obviously symbolic date—May 1, international workers’ day—and staged a great rally in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolívar. The rally would serve both to pressure the Senate to actually approve the consulta and as a campaign launch for the consulta, an epic and defiant show of strength to all his opponents.

For the occasion, Petro announced that he would unsheathe Simón Bolívar’s sword and that it’d lead the rally, as a guide of the Colombian people. Bolívar’s sword is a powerful symbol that’s been used (misused) politically multiple times in Latin America. In 1974, the M-19 guerrilla famously stole it, returning it as a sign of reconciliation following their demobilization in 1990. In August 2022, during his inauguration, Petro ordered that the sword be brought out, defying Duque’s initial refusal.

Bolívar’s sword was paraded out by the presidential guard battalion and placed on stage during his speech. At his side, the head of the presidential office (Dapre) waved the red and black ‘war to the death’ flag (guerra a muerte) of Bolívar (the flag is more closely associated with Venezuelan independence).

Petro spoke for about an hour, in a fiery, radical and populist speech. Once again, Congress was his target. The president used the black curtain draped over the Capitol (to prevent vandalism) as a metaphor to build his diatribe against it, in particular the eight senators who voted against the labour reform in March. He held Pinto and Blel indirectly responsible for the murder of a petrista activist in Cauca, and vowed that he’d been avenged not with blood but with the victory in the consulta.

Reading out the 12 questions, he said that anyone who doesn’t vote for these reforms is a ‘slave-owning HP’ (hijueputa, son of a bitch).

Petro has insisted that the consulta is mandatory, because it is backed by the ‘constituent people’, the ultimate sovereign which is above any constituted power like Congress. Petro said that it was now up to the Senate to “speak directly and look into the eyes of the people” and to accept that Congress “obeys” to the people. Petro said that senators who vote against the consulta must be shown and exposed before the people, and that the people would ‘revoke’ them. He asked to make a ‘pact’ with the people: “not a single vote for anyone who dares to try to silence the people during the consulta.”

Petro ended his speech by symbolically unsheathing Bolívar’s sword and holding it, proclaiming that the liberator’s sword “commands and guides us in this struggle for the rights and freedom of the people.”

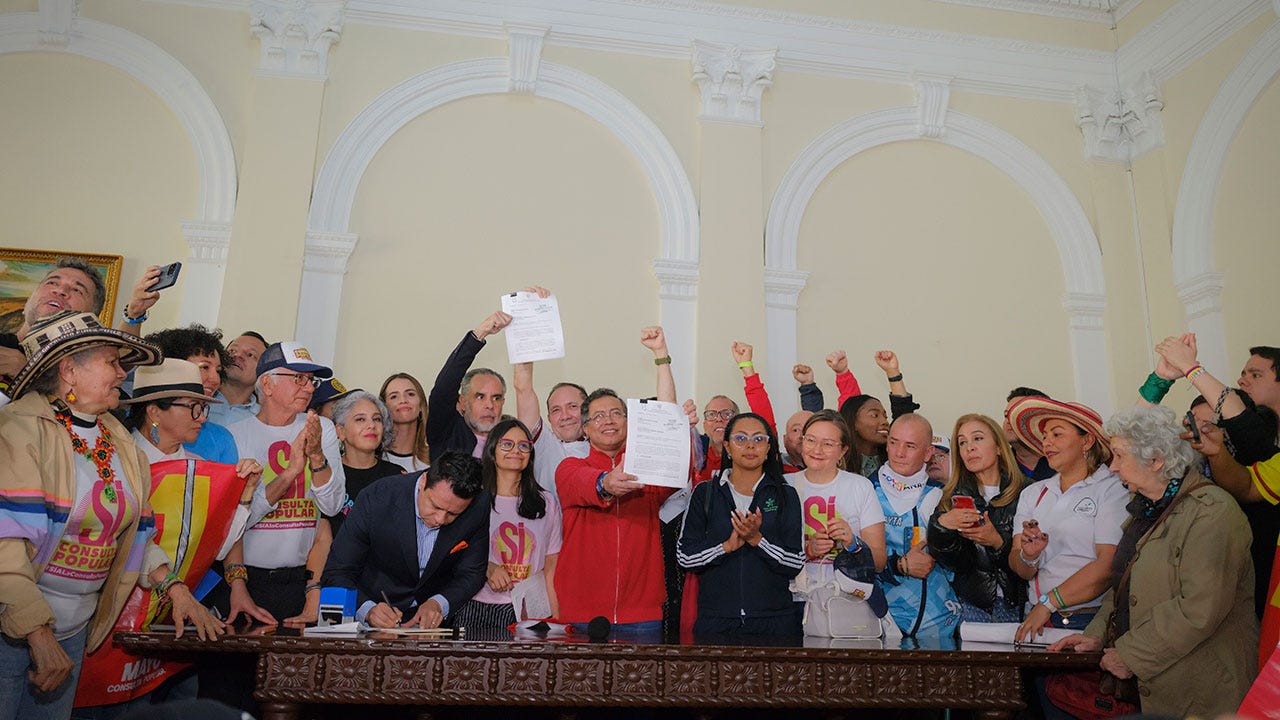

Following the rally, Petro formally presented the consulta popular to the Senate.

All while vowing to name and shame those senators who vote against and saying that the people would ‘revoke’ them, Petro tempered his radicalism by guaranteeing that he would stay within the institutional framework. He said that Congress wouldn’t be thrown out by force in a stampede, but rather in the regularly scheduled congressional elections in March 2026, followed by the presidential election in May and June 2026. At that point, the people would decide if “they want to go back.” Petro again said that he will leave office on August 7, 2026. Petro fancies himself as a great revolutionary, and his speeches may attempt to imitate Chávez or Fidel Castro, but he remains within the institutional framework of the constitution (no matter how much he dislikes aspects of it).

His ministers have also stuck to an institutional tone. Sanguino, the labour minister, said that if Congress doesn’t approve the consulta then they’d pay the consequences in March 2026. This suggests that, in this adverse scenario for the government, there’d be no extraordinary measures.

It’s unclear whether senators will be pressured by Petro’s speech and show of force. In an open letter to all members of Congress, Efraín Cepeda, the Conservative president of the Senate, wrote that Congress was facing an ‘unprecedented assault’ with ‘intimidatory mobilizations’ and that never had a government pressured the legislative branch with such intensity and confrontation. He invited members of Congress not to let themselves be intimidated by the government, reaffirming their independence. Bendetti denied any ‘assault’ on Congress and that the only thing the government had said was that the people wouldn’t reelect the senators who vote against the consulta. In a statement, the Partido de la U condemned Petro’s words and behaviour on May 1 and called on him to respect the democratic process.

Cepeda has announced that he hopes to open the debate on the floor of the Senate on May 13, with the vote to be held on May 14.

The government isn’t waiting for the Senate to start campaigning. On April 24, Petro and Gustavo Bolívar (still in public office as head of the DPS) inaugurated the ‘citizen committees’ for the ‘yes’ in Soledad (Atlántico). On May 6, Petro held an event outside the palace with some 4,000 SENA apprentices to promote the consulta. On social media, official government accounts have promoted the consulta with the hashtag #SiALaConsultaPopular. This is in quite flagrant violation of the law.

The government feels that whatever happens is a win-win for them. If the consulta is greenlit by the Senate, the government claims victory and can spend the summer campaigning and controlling the narrative—of course, the actual consulta popular and ‘being counted’ remains a risky gamble. If the Senate rejects it, Petro will have the best example yet of the ‘institutional blockade’ against him and can attack congressmen as enemies of the working people, with eyes on 2026.

The government feels that the political moment has changed. A charismatic, rable-rousing, populist Petro, haranguing the base against the ‘oligarchic’ political class opposed to workers’ rights, is more comfortable and favourable ground for the left going into an election year. There’s limited indications that Petro’s approval ratings have bounced back a bit (though still very much underwater): in the latest Invamer poll (April 2025), his approval rating rose 5% to 37%, the highest it’s been in two years; in a Cifras & Conceptos poll, his favourability is up to 45%, a two-year high and 57% support the consulta. Only time will tell, but the opposition, if it doesn’t adapt to the new context, risks being caught up in a world of Petro’s making.

Regardless of whether or not there’s a consulta, the 2026 electoral campaign is very much underway.